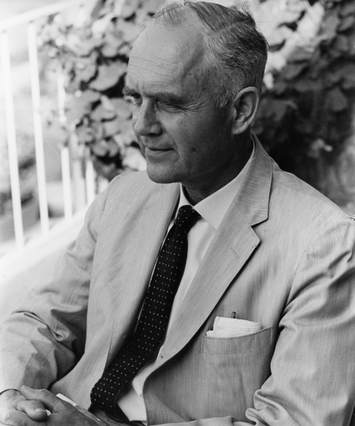

Malcolm Mackay (MM) recorded this talk with Margaret (Margie) and Michael (MB) Barrett in Edinburgh in September 1979

Well, Michael, you have been associated with the work of Moral Re-Armament for a very long time and in the earlier days with the Oxford Group and you of course are a Scot. How far back does your memory go as far as your life is concerned? Was it always associated with Church and things to do with the Christian faith?

Mike: The first memory I have was yowling in bed when the zeppelins dropped their bombs in the water of Leith. It must have been about 1916 and I was 4. I don’t remember being christened by Alexander Whyte but he was a great figure in Edinburgh life, at St George’s West, (St George’s, as it then was) and we were baptised by him. It was his widow who later met Frank Buchman in Edinburgh and finally invited Buchman to bring the team of the Oxford Group to Geneva and booked 30 rooms in a hotel there. We got to know her quite well later on.

MM: His mother was apparently a very fine person and he himself was illegitimate, I understand.

MB: Yes, he was and he used that fact with the congregation.

MM: When he was inducted that very first Sunday he brought his mother in on his arm and put her in the minister’s pew before he conducted the service - the story goes that he had actually been told by some of the Session that it might be better, under the circumstances, for his mother not to occupy that pew. He made his position clear from the start.

MB: From what I hear I think he scolded the congregation too. He used to say they suffered from every virtue except a sense of sin.

MM: Whyte and Black ...

MB: Two Blacks. Hugh Black from America and James Black from Edinburgh, and then there was Archie Black who was an actor. Of course most ministers, to be good, have to be actors too, as you know Malcolm.

MM: At that time I think you could say that St George’s West was the principal place of preaching in Scotland

MB: Yes, certainly they used to queue, long queues at night, for the evening service. That of course attracted more people and the Blacks had a real platform in Edinburgh in the church - no question. In between them was Dr Kellman who was a very successful preacher there and a very-much loved minister. I didn’t know him so well. I came more in the time of the Blacks.

MM: What other great men had an influence on you in early days?

MB: Edinburgh was quite famous for its medical faculty which in those days was streets ahead of London. We had JY Simpson, the inventor of chloroform, and his wife and subsequently his widow, Mrs JY, was a great friend of ours and helped Margaret and me too with her friendship later on in America. She was right in the work of the Oxford Group later. Then of course there was Henry Drummond about that time, who was so well-known in Edinburgh, especially for his work with scientists and the universities. I think he was a forerunner as a power in the changing of men and younger people. I think this meant a lot to Frank Buchman also - how to win and capture the scientific mind and the younger students who were looking for the meaning of life without perhaps finding it.

I never knew much of the Moody and Sankey movements - I used to hear of them from Buchman. Buchman used to quote their old hymns and Moody’s sayings, like when somebody in a railway carriage told him how he ought to be doing his work. Moody asked his critic how effective he was with his own work and the replay was that he hadn’t been very successful, to which Moody replied ‘Well I prefer the way I do things to the way you don’t!’

I first came across the Oxford Group in my second year at Oxford at the university. The man in the rooms above me was so different that I asked him where he had been. He said ‘Well come along next Sunday evening to Corpus rooms and see’. So I went and they were the rooms Reggie (Holme) knows which were directly above the furnace! We were promised a dire fate if we didn’t change.

What attracted me about it was that people were real about where they had to change. I had been in India the year before on one of these schoolboys’ Empire tours and I really felt the need of change. You can’t go to a place like India or the Third World without realising some change is needed in us in the West. I had gone to a guru and said ‘What must I do? He replied, ‘Live a good life’ - but that was a bit vague for me. In Oxford I discovered these four standards and then somebody had the initiative to ask me to tea. This was Kit Prescott who is featured in ‘Good God, It Works!’ He had me to tea and had me down on my knees to give my life to God. All in the same week.

Kit told me to keep a time of quiet every morning, so I started. I knew the first man I had to see was a chap whom I disliked thoroughly and despised, so I went to talk to him and to apologise. I found he was thinking about committing suicide, so I think I was able to help him and that certainly helped me.

MM: At this time - you have mentioned Kit Prescott, Reggie Holme (of the Motorcycle Club). Any other persons particularly with whom you formed a new friendship at that time?

MB: Well, that goes for everybody. We had a Scout (servant) in College who was very senior and rather dictatorial. We didn't get along very well so I was able to go and apologise to him, and we became the greatest of friends until he finally died after more than 50 years in the College. He was a real character called Cadman who became legendary in the College. I believe when the Queen or the Queen Mother came to dine in Hall one night later on, one of the poor Scouts in College dropped a silver salver with the vegetables and they tell me at College that Cadman’s language has been remembered by everybody present.

Frank Buchman had these Assemblies every summer as you know in Lady Margaret Hall and St Hugh’s - four at once one time. I was invited along there and went. Then I was invited to clear up Frank Buchman’s room a bit, which was showing signs of a busy life and particularly get his letters filed and some of them answered. So I spent that first summer for a couple of months trying to deal with his correspondence. Through this I got an idea of the kind of life he was leading.

MM: At this time I have the picture that Frank Buchman didn’t have a regular secretary and you must therefore have been regarded by Buchman as a young man of considerable promise to have you admitted to the confidentiality of being his secretary at this time.

MB: Maybe so. Or maybe somebody was trying to help him and didn’t have all that much free time and thought I needed a bit more employment. You can look at it either way you want.

MM: Anyway you must have got a tremendous insight into the way he was working, the size of his correspondence and the nature of the work he was doing at the time.

MB: Also I had the chance to meet people. I remember Charlie Andrews was there (CF Andrews) who was a great figure in missionary work in India. He had really won Gandhiji’s confidence and friendship and was regarded somewhat as a saint. And who changed, I think, Sadhu Sundar Singh, who wrote that book ‘Christ in the Silence’. Anyway I got to know Charlie Andrews a little. He used to shuffle around in his beard and slippers, a great character, in LMH.

Reggie Holme: He had a little battered suitcase with all his worldly possessions in it, which seemed to be absolutely minimal and truly apostolic.

MB: Frank was very devoted to Charlie Andrews as well as to so many others.

MM: So you have the picture then of Frank Buchman, not starting something completely separate and fresh as it were, but right in the main stream of the evangelical onward movement of the church militant of the day.

MB: Not perhaps just the evangelical side of the church, but the whole church. I think Frank Buchman never thought he’d brought anything new. He just made it effective.

MM: So after you graduated, where did you go from there?

MB: I thought of going to New College, which is our theological college in Edinburgh but luckily failed in Hebrew because I only gave myself a month to pass all the exams. Then I went round the depressed areas. This was in the 30s, when there was so much unemployment. I packed a bag and went through Fife, the coalfields, and Clyde, the shipyards and South Wales, the coalfields. I got some experience that way. I stayed in digs, got to know some of the anarchists, the miners and the revolutionaries and found out how people were thinking. It was a very difficult time for many countries, particularly Scotland, with very high unemployment and a real revolutionary spirit around, out of which the group of the Independent Labour Party developed later - Jimmie Maxton and the other MPs, whom I had a chance of seeing later about MRA. The ILP was really led by these 4 rebel ‘red’, Clydeside MPs. They weren’t really ‘red’ but people described them as red. I also went into my uncle’s business in chartered accountancy for a year, for which I got a reward of 10 guineas at the end of the year for my work on the accounts. I am sure it wasn’t worth more! Again it was a good experience to get to know the other people in the office. Many Scots of course made their careers by being CAs, so I was glad to get to know it.

MM: So about this time as a young man, having your degree behind you, having felt that the regular training for the ministry wasn’t to be your lot, and with this experience of a very hard world, you must have been thinking very seriously about what you were going to do with the rest of your life, and what was the thing that was your real calling.

MB: I don’t know about vision for my life, but I had a lot of turmoil as to what to do. It wasn’t very easy, I found, to decide. My uncle in Glasgow who had a big chemical business offered me a job. I wasn’t sure I should accept it until I was sure God wanted me to do that. So finally he withdrew the offer and said ‘How would you deal with the Russians?’ Well of course with a bit of training in MRA I might have learned how to ‘deal with’ the Russians cos they have an ideology which we rather need - something better than communism. However, that went by the board.

I was beginning to understand a little about this by this time. Finally I went down to a houseparty of the OG at Oxford to get some more training and more experience. Being an Oxford graduate it was suggested I went to London to the back room at Brown’s Hotel and packed books and learned some practical things also. Frank Buchman always had the idea that if you had a university degree you had to start learning things which you hadn’t learned at Oxford. So I packed books for a year in the back of Brown’s Hotel. It was good for me because you met such interesting people. These temporary rooms when Buchman was in London, were the headquarters of the Oxford Group and people of all types used to come in. It was fascinating for a chap who perhaps hadn’t met so many people to meet these different types and to learn how to answer their questions. You got some terribly interesting situations. This was probably about 1934.

MM: So at this time the OG was really beginning to make a tremendous amount of headway and becoming world news.

MB: Yes page 2 of The Sunday Chronicle featured the change in Beverley Nicholls, for instance (the man who wrote ‘Cry Havoc’) and then we had Amy Mollison. The world famous pilot and her husband Jim. Various stories like this hit the headlines so my job was to send out these pages of a paper to those who wanted it and to answer the questions of those who came in.

MM: You have mentioned some of these famous names. One of the things that was said about the OG and these days was that it was very interested in ‘famous names’. What about ordinary people? You have mentioned a lot of people coming and going. Could you give us some idea of the kind of people that came and went.

MB: All this talk about famous names - just like if you see a shoal of mackerel - you see a couple come up to the surface and skip the surface, but underneath there is a shoal. You wouldn’t have the few above if you didn’t have the shoal below. This is the same about the OG really. I remember one day a young couple came in and they said they wanted to get married. Then they explained that one of them was married already so wanted a divorce first so he could marry this girl. Really I didn’t know what to say. I happened to have a Bible, for some reason I looked up this page and it was one of these lucky dips because I opened this page at Matthew - I don’t know what chapter it is, 7 or 8 or somewhere - and it gives most explicit instructions of what to do in a case like this. I had never read that passage before so I just handed the Bible to these two. They read the passage, said thank you, and went. It was up to them then but it was so plain even I could understand it!

You know the porters at Brown’s Hotel were a great help to us. White and Berridge were marvellous friends of ours. The page-boy then was John Vinall (with whom we have kept contact all his life, even in his retirement). He then became porter in place of these other men and then I think was porter for 25 years. So these porters were a great help because they would receive the people who came in and then come in and tell us that so-and-so was waiting to see us. One day White or Berridge came in, I was working at the books or something, and said ‘There is a gentleman to see Dr Buchman.’ I said I would be out as soon as I could. After a minute or two I went out and here was this tall gentleman sitting in a chair. I said ‘You wanted to see Dr Buchman?’ He replied yes, please, ‘I’d like to see Frank’. I said ‘May I know who’s calling?’ He said ‘This is Paul’ and I discovered that this was Prince Paul of Greece. So I quickened my step a bit and went in to see Dr Buchman and tell him that Paul was there. This had an interesting sequel, by the way, which I will tell you later on.

MM: At this time the whole picture moves to the Scandinavian area I believe - possibly one of the major areas of OG development. Were you at any of those great OG gatherings ?

MB: Yes, but we didn’t all get to go because I think John Vickers and I were asked to arrange the travel of the delegations going from Britain to Denmark for the big meetings in Copenhagen at the Oddfellow Palace. I had the £30 that I had left home with, plus my suitcase when I went fulltime with the OG. I put this in a bank in London - the British Linen Bank in Piccadilly. I had to draw this thirty quid out and put it in a current account and start off travel arrangements for 500 people to Denmark. They all got over there safely and got back again. John and I together had to arrange it.

MM: Looking back on the time when there were these tremendous movements and great numbers of people involved - at that time hopes must have been running very high that there was going to be a great shift toward God and a new basis of living in the nations. Did you have a great sense of this occurring at that time?

MB: Oh yes you did. Anybody who was there must have felt it. There were countries, largely Marxist, possibly agnostic or atheist, certainly materialist like we are now, yet with a great hunger for a Christian experience. I remember Lawson Wood and I were sent over to help with an assembly in a place called Hasluf in Denmark where so many people came that we had to put out on the radio that they needed to bring their own bedding. Many of them came and just used newspapers or something. We ourselves slept on the floor of a headmaster’s study. We got so used to these immense crowds of people, finishing of course with that rally as you remember at Hamlet’s Castle in Elsinore with 10,000 people at Easter. It was a tremendous experience to us and Margaret and I went back to Norway and Denmark just a couple of months ago to meet some of these same people.

MM: Now you have brought Margaret into the picture I think it is time that we did direct some questions to you Margaret. Perhaps we had better go back, if you don’t mind, to get some idea of your own background. You obviously are not Scots!

Margie: No. I am Welsh on both sides of my family. My mother and father both Welsh but I wasn’t brought up in Wales ... I was brought up in London. My father was a doctor in London and I was sent to boarding school in Sussex. My mother’s father was Lloyd George who very much WAS Wales. We met interesting people when we were quite young - we met Winston Churchill and Philip Snowden and some of the names that one associates with political life. Of course we always took part in his political campaigns, even if it was only licking stamps and writing the envelopes. Yes, I am a Liberal.

The very first time I ever heard of the Oxford Group was in Canada in 1938. Then 4 years went by. I didn’t like these four standards that I kept hearing about so I didn’t really do anything about it . But it was interesting that I kept running into it when I got back to England. That was between 1938 and 42, I kept running into it. It was seeing one of the plays in London at that time, a play called ‘Battle Together for Britain’. It was the early years of the war. The thing I remember most about the play was the scenes of great people who had done things for their country, people like Florence Nightingale, like Lord Shaftesbury and others. It made me long to be the kind of person who could do something for my country.

It was rather unexpected really because quite out of the blue I was offered a job to take on a thing called the Girls’ Training Corps for Wales. This was a youth organisation started by the Minister of Education for girls of 14-18, to help them play their part in the war effort. Their older sisters were all called up when they were 18 and these girls wanted to do something to help serve the country. So we gave them training. I was asked if I would be the organising secretary for Wales. My mother was on the committee and she was asked to offer me the job, which I turned down immediately because I knew it would mean leaving home, leaving London, leaving all my boyfriends and parties and all the things I loved It would mean going to live in Cardiff in south Wales, and I did not relish that thought. But that night I didn’t sleep at all and I really took a good look at my life. I saw that I could go on the way I was, which would be no use at all for the rest of my life, or I could choose to go God’s way. If there was a God (I wasn’t sure he was there) but I knew that if he was there he must have a plan for my life and that I had not yet found it. Also I think deep down in my heart I wished I could do something for the youth of Wales, particularly. I felt I wasn’t the kind of person who could ever stick at anything worthwhile, so what was the good of starting? Then I remembered what people in MRA had said to me, that God could change human nature. I thought that if my human nature could change, then everything would be different and I could do the things I longed to do.

So at that point I decided that come hell or high water I would jump off the cliff into the ocean and give my life to God. He could have it, and I would take on this job, knowing nothing. I would live the way he told me to. So by the morning I had decided that I would take the job and I would live the way God meant me to live because I felt this was what he meant me to do.

So I told my mother in the morning, without telling her of all the struggles. I said that I had decided to take the job after all. Well, she was quite used to my chopping and changing and told me afterwards she thought I would last about 3 months. However fortunately she didn’t say anything except ‘Oh that’s fine’, and left it at that so I got the job.

I went off to Cardiff and it was a most fascinating experience because I was given 10 days training before I began. I didn’t know that there were about three and a half thousand girls to train, five thousand by the end of it and my job was to start these companies all over Wales. It meant I had to travel and call meetings and speak at them. I can remember the first day I got there being taken into 3 empty rooms and being told by one of the committee, ‘Well now, get on and furnish the rooms and I am about 20 miles away so if you need anything ring me up on the phone.’ I felt like going back home to London and throwing it all up.

However, I thought that if God had brought me here he must have a way of telling me how to do it. I didn’t even know what furniture you put in an office, nor did I know what prices you paid for furniture. I thought well God had better tell me now what to do. So my very first experience of guidance was making a list of the things I would need in the office, with a price by each item and then going to the shop where I was told (by God) to go. I found the items at the price and that’s how I got the office furnished. I mean, I had a list of possible shops but I didn’t know the city. But I had a very clear thought of which shop to go to where I would find which item at which price. Clear thoughts. At the end of the first day I thought this was the most exciting discovery I had ever made in my life, because there is a God and he can speak and he knows better than I do. That actually is how I did the job.

As it was wartime it was difficult to get some of these things because there wasn’t much new furniture being made. Some of it was second-hand and you didn’t quite know therefore the price that you should pay so it was all the more remarkable.

One of the interesting things I discovered in South Wales was that most of the girls I was dealing with were the daughters of miners, people I had never normally met in my life. The people who were working with MRA in South Wales were former miners, who had been communist for 25 years in some cases and who had found a new faith. The work that was being done down there was mainly done amongst the miners. Therefore for the first time in my life I came into contact with these men and women whose background had been quite different to mine and who had suffered terribly during the years of Depression when the men had been out of jobs for 12 years. These girls and the MRA team in S Wales all brought me into contact with the miners with whom I began to work. I couldn’t live this life on my own, I discovered I needed to be part of a ‘force’ and have the help and support of other people who were living by guidance.

Some of the organisational side of my job was a horror to me because I was hopeless at maths and I had £2000 of government money that I had to account for. I knew that the auditor would want to know about these accounts and I was absolutely terrified of this business of keeping accounts. So I prayed about it and then I had guidance. I knew I had certain items of equipment, of uniform for the girls, and badges and leaflets which had to be sold and accounted for but I didn’t have any idea how to do it. I had a sort of little mental picture when I asked God for direction about the number of columns I would need and I set it all out on a bit of paper. I said to myself ‘I wonder if this is what the auditor expects or not’. Then I remembered seeing up in the office above me an accountant by the name of Mr Gorne. I decided to go and see if he was in and ask him if I was on the right track. I knocked on his door and went in and explained who I was and asked his help and that I didn’t know how to keep accounts really. I asked whether this was the sort of thing the auditors would expect. He looked it all over, and then he said to me, ‘Oh yes, this is the way I would have told you to do it.’ I was dumbfounded really.

MM: In compiling this mental picture of yours, all your own intelligence undoubtedly was brought to bear on it, and yet, looking back on it you are saying there was something considerably more than your own intelligence at work there.

Margie: Yes, oh definitely, because I would have been in such a panic I wouldn’t have known where to begin. The fear of it went when I felt that God was in control. He actually did give me the picture, the mental picture, of how it should be done.

MM: You don’t think that it was just that you had been given faith that there was a God and this gave you confidence that you had never had before?

Margie: It was partly that because I was very afraid of doing anything with figures. It was certainly partly that.

MM: In Wales at this time, you were doing this work with the girls. You mentioned that MRA was working there. What more was happening in that field?

Margie: Well some of the most militant communist miners who had been causing go-slows and stay-ins and all the rest of it in the mines, had been very deeply changed. Their attitudes had completely changed as a result of meeting the ideas of MRA. They had begun to create a sound leadership in the mines in Wales. At the same time some of the managers, especially of one in the steel works in S Wales, who had also, through meeting MRA, changed his dictatorial attitude to the workers. As a result of his change he began to interest one of the very militant communist trade union leaders in the steelworks, a man called Jack Jones He had lost an eye in the pits when he was a miner and was a very bitter man. I actually led the first miners’ delegation to Caux in 1946 from S Wales, and at that time Jack Jones was still a communist. Because of his interest in his manager who had seemed to have changed his attitude, he decided to come with us.

I didn’t know what Jack Jones would do. I wasn’t quite sure how communists behaved. I thought he might throw a bomb or do anything. I honestly thought this. I didn’t know very much about communists and he was such a violent one that I really thought anything could happen. I was a bit afraid.

However at the end of the first week at Caux I was amazed one day to come into the meeting and see him standing on the platform, together with the manager of his department in the steel works, telling the audience why he had been so bitter and why he had devoted all his energies, his pay and everything to communism. He felt it was the only way he could help his colleagues. Then he said that he had been out on the terrace at Caux that morning and written a poem. He read out the poem. What it did to him was that he felt he had been out to destroy the other class, because he blamed them for everything that had gone wrong. Now he wanted to work with men like his manager to bring a new spirit and a new leadership to Britain. He had found a greater and a deeper revolution than he had ever found in communism. And this was what his poem was:

I contemplate and bow in awe

Before God’s master plan

I watch the miracle superb

The change in selfish man

The snows on Dents du Midi

Are but the robes of grace

God has a plan for every man

And each one has a place.

In his own words he said that for the previous 28 years he had never written anything of a spiritual nature because his pen had been entirely devoted to Marxist theory. He very deeply changed, not least toward his own wife because she had not thought much of his communism. He was always away from home, was a bit of a dictator at home and didn’t really care about the home. He very much deeply changed towards his wife and his home and the house was united and happy where it had been very miserable before. Those two men not only did something for Wales but Jack travelled with other miners to America, to Germany - where he told his experience there as well as in Britain. They met Senators when they went to America and I remember they asked one what he would do if he sat next to a communist, how would he change him?

MM: So when you went to Caux you took with you a large delegation including Jack Jones. What age were you then?

Margie: I must have been about 25 or 26.

MM: There must have been international leaders of all kinds when you got there. I suppose with your background however it wasn’t all that difficult to mix with celebrities.

Margie: Well, I did learn to walk - I took my first steps - on the kitchen table at No 10 Downing Street. I lived there only as a child, from about the age of 8 months to about 3 years. I don’t really remember it, other than the kitchen and the nursery which was at the top of the house. Yes, Michael Barrett was there. I had met him two years earlier when he had come to Britain to prepare for D-day. He was in the American 8th Air Force at that time, and he was certainly in Caux then.

MM: Now the picture one has of the great events of the middle 30s was this building up to the great gatherings in Scandinavia and a really sizeable force at work in terms of changing the climate of world feeling. But of course we all know that a little further south at Nuremberg and other places there were other forces gathering. It seemed as though it was a race with time against chaos. Can you reflect on that period Michael and what the OG was doing and thinking in the context of the world events?

MB: It was obvious that things were building up to a real crisis, and material re-armament was starting in a race between different powers. This was where Frank Buchman was given this idea of moral re-armament, moral and spiritual re-armament as the urgent need in the world today.

MM: People in later years may wonder why the name Moral Re-Armament came about but it relates specifically to that period when there was a race against material re-armament that was likely to destroy mankind.

MB: I don’t think it was so much against it, because Edison for instance when Secretary of Defence in America, said ‘Moral Re-Armament shares equally in importance with material re-armament in these critical days.’ Remember that the west was preparing for defence against the growing menace of Nazi Germany. Buchman did not oppose the material re-armament of the west but he felt moral re-armament was necessary not only for winning the war but also for winning the peace after the war.

MM: So, at this time you were working fully with Buchman and MRA and saw the war closing in. Where were you working when war broke out?

MB: We were in the Middle East first and then I went with Dr Buchman to Freudenstadt in 1938, when he had been asked to give the keynote speech for June (his birthday) to an OG meeting in East Ham in East London. In preparing this he had the idea that he should use it as a call for moral and spiritual re-armament in Freudenstadt in Germany, Bavaria. We had come across this general thought from a Swedish trade union leader, called Harry Blomberg. We worked on this and wrote down our guidance each day. My job was to type it out with a few others who were there too, and gradually we worked out this speech for Dr Buchman on Moral Re-Armament, which was the headline the press gave it, and which he gave in East London in June 1938.

MM: It must feel rather strange now looking back to that moment when the name had not yet been born and to realise that you were there as a midwife to it. Yet the thought was one which originally came to Buchman in the Black Forest, was it?

MB: Yes, we were walking in the lovely forest which it is there, near Freudenstadt, and he dictated his ideas as they came to him. I actually wrote it down on a piece of paper against a tree, then went back to the hotel and typed it out.

MM: So the speech was prepared in Germany and then was delivered in East Ham. That’s prophetic in itself isn’t it, considering what was to happen.

MB: Yes, the labour movement began too there, so it was a good send-off. The genesis of a British trade union movement began in the factories in the industrial areas and also in East London. In Keir Hardie’s day it was a very suitable day for Buchman to be invited to speak to all the Mayors and the workers of East London as the birthplace really of the British labour movement.

MM: Not only in Scandinavia, but also in Britain, there must have been a sizeable movement taking place to be able to take the East Ham Town Hall and get all those celebrities together for this keynote speech.

MB: Yes, I think it articulated a need which so many people felt then and have done ever since. That is why, really, MRA spread as it has, because it expresses a need by the ordinary folk for some change in society.

MM: So the name ‘MRA’ has stuck to the work of the Oxford Group and it was a work that in the first instance was directed towards putting a moral and spiritual content into the struggle against tyranny. Like many other names, such as the Methodists, its origins have given it a name which has stuck and become a badge of honour across the world. So, 1938 June, East Ham, the birth of Moral Re-Armament - recognised by the press, called by that name. Then the coming of the (second world) war. What happened as far as you personally were concerned there?

MB: A bit before the war Buchman had gone to America to initiate the campaign of MRA over there, following the launch in Britain. I got a cable when I was in Scotland asking me to come over, so I went over just before the war started. We continued our work as hard as we could go in America. Then, of course, most of our own folk in MRA had joined up in the forces in Europe and were already out on the battlefronts. We were asked to continue the work of MRA in America by the British Embassy because at that moment we were greatly occupied with the Lockheed aircraft factories on the West Coast.

Then some people who had hated MRA and wanted to stop it began to spread the rumour that we were pacifists and attacked us on these grounds, which were quite untrue. However the campaign in the press was mounted in America and the New York Draft Board insisted on drafting us into the American forces. At the same time in Britain the attempt to get at least a nucleus of our people reserved, 12 men, was under great attack. Some of us were drafted into the American forces. I went down with some of my friends to the basic training camp in Virginia and into the Air Force training base in Florida.

Then we were commissioned into the American Air Force as officers and sent back over to Britain for D-day.

MM: Just getting back to the attacks on MRA in Britain in particular, where it seems to me 12 men out of the great movement that was now of such dimensions that we were discussing earlier, 12 men was only a tiny residue of people and yet ... Why was there such a vicious attack on it to want to virtually destroy it by having the last few of its fulltime people drafted?

MB: I suppose some people thought by scattering us in different places they would reduce our effectiveness.

MM: Why would they want to do that?

MB: Well it has always been the history of a militant Christianity that you get a militant counter-attack.

MM: I see, your feeling is that there was this counter-attack because of the distinctive Christian challenge of MRA.

MB: Yes, we were out to give a Christian ideology to Britain. We were out to answer the non-Christian ideologies in the rest of the world. Of course you get fire-crackers.

MM: During the war years then you were in the 8th Air Force and during those same war years things were being prepared in America for the days after the war was over. What was Buchman doing during those war years and as the war drew to a close?

MB: Well our work in America, as in Britain, was based on the essentials needed for a sound national life. For instance the handbook in America, which General Pershing, the head of the Army, wrote the foreword for, was based on sound homes, teamwork in industry, a united nation and how to achieve it. In Britain it was built on a little booklet called ‘Battle Together for Britain’ which called for national teamwork in Britain to resist the menace of the Nazi ideology and to build a sound Britain. Of course, the greatest allies these ideologies have are the weaknesses in our own society. If we could answer some of the disunity and other divergent tendencies in our own nation we would be that much stronger.

MM: It is a message not only relevant to war time but relevant to today as well.

MB: It was a great help also to me and others I know to realise that all our colleagues in MRA in different parts of the world were already working out the truths that we had learnt in MRA in action, many in very vital military action which cost them their lives. Or in courage during Occupation, like Freddie Ramm and others who died as a result of their captivity and stand for MRA in Nazi prisons. In Norway a lot of the Resistance came from those who had taken part in the leadership of MRA before the war. Looking back, it was as if God had been trying to prepare these people and these nations for what was coming by building a structure of something that would last through persecution, occupation, military action, into the future, and come out as girders of a new society post-war.

MM: Now let’s move on past the war years to the time when Margie arrived in Caux with her contingent from Wales and a new era was opening. Could you give us your view of what led up to the story of Caux, as you saw it developing, the planning of the people behind it?

MB: It was all so impossible, as most of these ventures are! Of course some of the Swiss trained in MRA had come over to America before the end of the war. They had seen what was going on there and went back with this conception of a place like Caux as a centre for all the nations in the immediate post-war years. Switzerland was the only place to which all these nations could send their people. The Swiss, with terrific courage and faith, got hold of and bought, with their own sacrifice, the centre at Caux. Then people began to come. We landed with Dr Buchman in time for the opening session. As proof of how unexpected Buchman was, he made only one comment. He looked around the assembly and said ‘Where are the Germans?’ This was the last thing we had thought of - getting the Germans, already under occupation.

People went to work and the delegations from Germany began to arrive. Of course this provided a focus for what was to become a reconciliation of the warring nations in Europe and beyond. Little did we know when we started it that this would happen and happen so quickly.

MM: Do you feel that there were people there who were horrified when he made this remark?

MB: I should say so. You only have to know the story of Irene Laure and the others who suffered so cruelly under German occupation to realise what it meant to them to meet the Germans again.

MM: So Buchman at this time was deeply imbued with the whole concept of reconciliation and the basic concept of the Christian doctrine of the Cross.

MB: Yes, and he knew you would never get peace in Europe unless you dealt with the bitterness and hatred underlying the state of mind in these countries. It only took a few people to change, courageously, first - like Mme Laure and some of the Germans - to build a structure which changed the whole future.

MM: Now Margie, you were there at the opening session too. Were you aware of Michael being there at the time?

Margie: No, not at that point. No. I had simply met him a couple of years before when he had come over in uniform but I didn’t think anything more about him at that time.

MB: But when your father died was probably the point at Caux.

Margie: Yes, that was the following year, 1947, when my father died. He had been very ill and I had to get home quickly. I remember Frank Buchman - when I went to tell Frank that I was having to leave, he turned to Mike who was there and said ‘You see that she gets on the plane and gets home as quick as possible’. I think from that moment, yes, I thought perhaps our lives would be intertwined.

MM: Fine. So when were you married? What year?

Margie: 1948, a year later. We were married in Wales, in my home village of Criccieth, North Wales. We had asked Frank Buchman to the wedding. He didn’t give us a reply for a long time and then he suddenly announced to somebody else that he was coming to our wedding, bringing 150 people with him, which were the cast of ‘The Good Road’, who were then giving their show in Holland in The Hague. He announced that he was coming to the wedding, plus all the cast.

MM: What about the place where you were married? Did it hold that number of people?

Margie: We just squeezed them in and managed to get accommodation for quite a lot of them in the village. It was of tremendous interest to the people living in the village because they had never seen people from so many different nations.

MB: There was only one policeman in Criccieth, called Mr Lovely, and I was interested that the people in Criccieth sold the window space to the visitors, opposite the chapel, including the Scots, so the villagers were taking advantage of the occasion.

MM: It must have been a thunderclap to you. Your father had died so your wedding must have been something of a - well one of those problems that you required the advice of the senior accountant - and here you are now faced with an acceptance, plus all those people. What did you feel like?

Margie: Rather overwhelmed at first but then we realised that Tirley Garth was not very far from my home, about two and a half hours. They put up quite a number of the people and then we had other friends in different parts of Wales. Some of them were able to come by bus in a day. South Wales had a busload that came up from Cardiff and went back in the same day. So we managed. One way and another.

MM: A thing like this must have hit the headlines locally, if nowhere else, surely?

Margie: I can’t remember now! Can you? I think it did yes, local papers with pictures and things.

MM: And Buchman himself was there. Who married you?

Margie: Alan Thornhill married us and Frank Buchman gave us the Blessing in the Chapel. My brother gave me away. I have two brothers, the older of the two gave me away.

MM: Now you have told us that you are a Liberal with the very best of Liberal credentials and you are working with MRA in Wales with people who have got every human right to be deeply bitter and resentful. Did you feel that perhaps what you were doing might have been taking the edge off their resentment? Or - you have spoken of personal change - did you really feel this was coming to grips with changing what was wrong in that situation?

Margie: I found these men and women had every right to be bitter towards somebody like myself who had had everything and had never had to go hungry and never had to suffer in that way. They felt that people like me hadn’t cared, which was true but I found that, when I was honest with them about the way I had been living and the way I wanted to live, I wanted to change in order that these things would not happen again. Then I found there was no gulf between us, that we were the same and we could go ahead and fight for the kind of Britain we wanted to see together.

MM: So out of what was a potential class war situation it moved to a new unity of purpose.

Margie: Very much so, because we spoke on the same platforms together and we were able to speak with a united voice to our country, rather than a divided one.

MM: During this time when there were these attacks being carried out on the work, I take it there were probably also areas of support that came to the surface too.

MB: Very much so. Indeed I don’t know which one followed the other. This interest in MRA grew a great deal in Britain. I had been working in London and went up to Skye for a fortnight’s holiday with my family. During that holiday, I had the idea of what it would mean to democracy if the ideas of MRA were accepted, and how it would appeal to the democratic heritage of Britain. So I wrote out these ideas and gave them to Frank Buchman and the others who were then in London. Between them they put together the substance of it and had the idea that it should be published in The Times in the form of a letter, a call for moral re-armament.

I remember well that friends of mine in MRA then, Roland Wilson and John Roots and others, went round to see the statesmen at that time, some of the senior statesmen in Britain, to talk it over with them, and the result was that a series of letters were published in The Times, calling peoples’ attention to the importance of MRA and the moral values in democracy. They were signed in the first instance by Lord Salisbury in the House of Lords and then others - former Prime Ministers and people eminent in public life. To me this was very interesting because it seems to me that if anything like MRA is to be valid it must be applied by all sections of society, the top as well as the bottom. I began to realise for the first time some of the texts in the Bible where it talks about ‘the government shall be on his shoulder’ and why Christ was called ‘the mighty counsellor, the Prince of Peace’. It seems to me that this is an aim that is big enough for everyone to take into their hearts and minds and could easily become a reality, if you have a response from the ordinary folk and the courage in leadership from the others.

MM: What was the response of the media at this time? Were they receptive to these letters?

MB: Yes. Of course you remember that the campaign was linked with the names of Bunny Austin and others in the sporting world. I remember when that first poster was designed illustrating Bunny’s book about MRA, his handbook as it were, it had the four standards like four great pillars with a cross-head ‘MRA’. This was the poster put up in the great meetings, in Madison Square Garden in New York and in London, calling for Moral Re-Armament nationally. Bunny Austin’s book was called ‘Moral Re-Armament, the Battle for Peace’, and I think it went to about a million copies.

MM: A little later, then, you were over in the United States, you were drafted and received a commission. A commission to do what?

MB: It was an ordinary commission in the air force because, as you remember, the Americans serving with the Eagle Squadron in Britain were allowed commissions and reciprocally we, who were serving in the American forces, were allowed commissions. We were assigned to what was called ‘orientation’, which had been set up by General Marshall in the US forces. He had been so disturbed by the numbers of GIs, American soldiers, who were sent overseas - remember it was the biggest civilian army in history - without really knowing what the war was about or what their part was. He felt that something was necessary to interpret for them the purpose of the war and the part that each person could play. So this orientation programme was set up to be activated in every unit of the US forces down to platoon level.

With the commission some of us were sent out as orientation officers. I came over first of all with the 9th Air Force and then transferred to HQ of 8th Air Force, which then comprised about 250,000 men, based on the airbases in Britain and later in other parts of Europe.

MM: So you had a good deal to do then with the orientation of a quarter of a million men.

MB: Yes, with the command structure. General Dolittle issued a report and a pamphlet to every one of the quarter of a million men. We followed it up with a film, stressing each man’s part. Then we followed it up with a carefully-planned programme on the basis of what we called the ‘theme of the month’ when one theme of this teamwork with the RAF, or whatever, would be emphasised throughout our command.

MM: Mike, during that period of service during the war, were there particular times when you felt guidance brought a new plus into the things you did, that got you out of tight corners or answered problems that were unusual?

MB: Yes, of course life was and is full of things like that. I remember one day walking into my HQ office and my boss sitting at his desk with his feet on the desk, in his usual way, with a pencil. He looked sort of happy so I asked ‘what’s up?’ He replied, ‘Well I have got the answer to our problems with our high HQ, which we had been having some rivalry with. Then he said ‘We will turn over the whole of our theme for next month into the importance of the work they are doing.’ We had to work this out with our whole programme. It took the form of speakers at all our bases and the team of the month in a pamphlet form and all kinds of command-wide efforts. I was with him when he met his opposite number from this high HG at the club in London. My boss went up to him and said ‘Colonel, I thought you would like a copy of this theme of the month booklet where we tried to explain the importance of the job you and your HQ are doing.’ I saw this chap, who was a regular Army officer risen from the ranks, with a great bull-neck. I could see the blood course down or up from his head right down his neck. He took this booklet and from that day we were friends. That showed me that things worked in an extraordinary way.

The other thing that happened was that we were all preparing for D-day, not knowing where and when it would come. We had gone up to see our CO - the adjutant, the chaplain and I. We had suggested that he publish a message for all our personnel - that he issue this message to everybody - 4,000 of them at this base near Newbury where first of all the paratroopers, then the glider, the airborne and troop carrier were going over for D-day. So we drafted one at his request, quite short, three paragraphs. He signed it and that night it went up on all the bulletin boards. The next day the fellows were off but we hadn’t known that when we suggested it. This was just a call for teamwork between all the services and putting our trust in God. Quite simple, but it came out at the right time.

The last instance I remember was when we were down at this base. My colleague Reggie Haile, who had come over from America with me in a troop carrier 439 thousand or 438 was up near Birmingham and I was down near Newbury. We had just had the head of The Times’ parliamentary staff to talk to all our fellows, 4,000 of them, about British Parliament and British government - Arthur Baker. I took Arthur Baker back to the Colonel’s quarters for coffee and talk before turning in. Arthur Baker was my Colonel’s guest for the night, having had this talk and worked pretty hard through 4 sessions during the day. There came a knock on the door and a chap asked if I was there and the Colonel said ‘Yes’, so I went out, and this was a Lieutenant - I don’t know who he was to this day - who said there was a message for me:- Lt Haile is up at his base near Birmingham and is not expected to live the night, he has meningitis. I thanked him and went back, the Colonel asked what the message was and I told him. I went back to my barracks and lay in the Nissan hut and prayed. At around 3 in the morning I realised that either Reggie was dead or had turned a corner so I went to sleep. 7 am the next morning I went to HQ and asked the adjutant if I could see the Colonel. He showed me in, and the Colonel looked up from his desk and said (Mike’s voice breaking) ‘It’s Lt Haile, isn’t it?’ I said ‘Yes sir’. He said, ‘Well you’ll want a plane, won’t you?’ I said ‘Yes sir’. So he picked up the phone and ordered a plane ready for Cap’n Barrett on the runway in 20 minutes with a jeep inside. We took off, went up to Castle Bromwich, I guess, trundled out the jeep and drove to the hospital. As we got to Reggie’s bed he opened his eyes. These things are very real when you go through them.

Margie: Wasn’t Reggie staying at Tirley when it happened, and Dr Reg Luxton was in the room next door and had just been researching into this particular disease. He was able to diagnose it immediately so he was taken down by air to this hospital and given the speedy treatment he needed.

MM: You must have been very close to Reggie at that time, Mike?

MB: Yes, we had been all through this. He had a fight to get through his illness and the weakness afterwards.

MM: Getting back to Frank Buchman himself, there are stories whenever one speaks to people who knew him. One is impressed by the fact that he was a person who never followed a stereotype path. Indeed you might even say he was “Buchman, The Unexpected” very often. Did you have any experiences of things that he did that to everyone else appeared to be particularly daring or unusual?

MB: I think this is a very true point because if he had not been the unexpected and non-conformist Buchman, we would have had a movement with an organisation set up with institutions and officials with salaries and red tape of all kinds. By the mercy of God, Frank and MRA have been saved from that because we are not a church, we are not an organisation. It is the leaven in the lump that we have to be. This has saved enormous expense and enormous complications, in my view. This self-righting or gyroscopic control that Frank Buchman had in his own life - when he would bring every question and every decision into the light of guidance ... It meant you could never predict with certainty what view he would take on something because he would bring it to a matter of decision according to the guidance of God received by him and the others concerned and not make it a subject of experience or good advice.

MM: When the miners from the Ruhr first came to Caux, I was told that Dr Buchman chaired the meeting himself and most of them were either communist or very much affected by the communists. Do you recollect those days?

MB: Yes, I do and I remember that Buchman would spend a long time getting to understand their problems and what they were thinking. But when the time came to give them the real truth of the Spirit he would do it.

MM: Have you had experience of people right at the very top of the social tree in Britain meeting the ideas of MRA and meeting the challenge of teamwork perhaps from people who have never been used to teamwork?

MB: Oh yes, a terrific lot goes on. It can’t all be in the headlines otherwise it would be self-defeating. You can’t publish things. I talked about Lord Salisbury earlier - he was the first one I had met when he came into Brown’s Hotel to see Dr Buchman and the others. It is a terribly convincing experience when you see a man in responsible public life who takes the programme of MRA so seriously that he makes a speech about it in the House of Lords, saying the problem in Britain today is not economic, it is moral. He was a very sincere, convinced person, convinced by a local friend of his. Then the initiative came for Buchman and some others in MRA to meet the political leadership at a weekend conference just to explain some more about it. You constantly meet people in public life, some come openly, some like Nicodemus perhaps privately, to find out how to be more effective. Of course, an advantage of MRA is that it is not an organisation that you join. It is something you put into practice and you don’t have to wear a big label saying what you are. That is not the point.

That trip to the Middle East that Dr Buchman took some of us on included Tod Sloan’s friend, Bill Rowell, who was a revolutionary in East London, a trained man, with Lady Antrim and Lady Minto, both Ladies-in-Waiting to Queen Mary. In Lady Antrim’s case to Queen Victoria. She came out at the age of 80 and over it on this tour of the Middle East with us and all as part of the team.

Their families thought they were absolutely mad at their time of life, to pack their cases and go out with Dr Buchman to the Middle East. By packing their cases I mean something quite real because, when we were preparing for the voyage we had to go to Vienna first by boat and train and then we had to fly to Sofia in Bulgaria and to Greece, to pick up the Hellenic Lines liner. When we tried to prepare Lady Minto and Lady Antrim for the boat journey we asked Lady Minto how many cases she had. She replied ‘27’, so by the time we were ready to go we had reduced it to 8. Then one of the party was brave enough to tell Lady Minto that the train left from the station at Victoria at 10 o’clock. She said ‘What do you mean 10 o’clock? Trains don’t leave at 10 o’clock. Trains leave when we are ready.’ We suddenly realised that she had been in India, of course, as the wife of the Governor-General and wife of the Viceroy. The Viceroy’s train, of course, left when the Viceregal party were ready and 10 o’clock meant nothing to her. Of course we had to try and get her there on time.

Then we discovered in Vienna that there was one lady’s maid who went with Lady Minto and Lady Antrim, a lady called Miss Forrest (Margie: to whom Lady Antrim had made a very real apology, hadn’t she, for being so dictatorial and superior). Miss Forrest came up in a great state and said ‘Her Ladyship is very nervous about this flight’. To tell the truth I was slightly nervous too because we were flying a Ford Tristar thing - Tri-something anyway, maybe a big Fokker - only 3 engines, one on each side and one in the middle of the fuselage nose which vibrated especially when we were trying to get up over some of the mountains. Then we discovered it wasn’t Lady Minto who was nervous at all, it was Forrest.

Tod Sloan didn’t come with us on that trip, it was Bill Rowell. Tod I think was busy back at home writing his letter for Bunny Austin’s book ‘Battle for Peace’ about MRA being God’s property, describing himself as a watchmaker by trade and an agitator by nature.

Bill Rowell and Lady Minto - no problems at all. Opposites attract! They got on famously.

MM: Buchman at this time:- you have talked about many countries that he went to, but earlier Margie you were saying that he had a great regard for Wales. On what do you base that?

Margie: The very first time I met Frank Buchman was when he had just come over from America and I was asked by the team in Wales to give him a birthday present, which was a book on Welsh folk-lore. I thought this was rather silly really. I didn’t think he would have time to read it. However, I presented it to him on behalf of the Welsh team and he thanked me very much. Then a few days later I was astonished when he stopped me somewhere and said ‘That was a very interesting book. Wales must be a fascinating country. I was so interested to read about Wales.’ I was very touched really that he had taken the trouble to read the book and that he cared about Wales. He came to Wales many times and also he did a transatlantic telephone call to Wales, to Cardiff Castle where we were having a great gathering. Yes he really did have a love for Wales.

We were with Frank in Northern Italy, in what was the old South Tyrol, and were staying in the castle of a friend of his who had just returned there after the war. Frank’s idea was to have these tea parties where he invited the Austrian population who were all sorts of ‘old’ families - the Dukes and Duchesses, and at the same time the Italian population, the prefects and governors of the different provinces, the officials of government. Feeling between the two was appalling. Frank really managed to bridge this gap between the two. But on one occasion, I think Mike was there with Edward Howell and they were just about to set off for Greece and Turkey. Somebody else was going to somewhere else, so we gathered together in Frank’s room and Frank said ‘Now we will pray about all these people going to these different countries.’ I, by the way, had lost a very precious brooch, an heirloom of my grandmother’s, which had disappeared from my bedroom. I had told Frank about this a few days earlier and said I was praying to find it but he didn’t say anything. Anyhow, he started to pray for these great ventures that they were all setting out on. Then suddenly in the middle of the prayer I heard him pray that I would find my brooch and I really was terribly touched. I thought, ‘Well he doesn’t just think about the great things in the world but he thinks of each individual and what they are worrying about, however trifling it may seem.’

MM: You had the opportunity of going back to Greece with Edward Howell some years after his wartime escapades there?

MB: We went to Greece from Italy, soon after the war. Just when the strife in Greece had finished between the communists and the others. We arrived at the airport in Greece when not many people were arriving. It was quite vivid to me because we went from the runway into the office where the immigration were. This inspector was behind a desk. He looked up at us very antagonistically and said ‘Passports please’ - actually I don’t think he said ‘please’ - so we put down our passports. As he was reaching for them he said ‘Been in Greece before?’ So I said ‘Yes, as a matter of fact, I have, and my friend spent 3 days in Crete, left for dead.’. There was silence. Then I saw him shut the passports and I saw his eyes brim with tears. He handed back the passports and said ‘Never forget any man who shed his blood for Greece on Greek soil is always welcome here’.

We went up to Salonika, to the prison hospital where Edward had been in prison following his wounding. He was down to half his normal weight, as you know, before he made this escape. He told me that the charlady who looked after the ward where they were billeted was also starving. She was just skin and bones and had tried to share her crusts with them. As we were revisiting this hospital, we were walking along some corridor retracing Edward’s steps for his escape, and we saw this very broad and rather stout woman somewhere in a corridor. I looked up to see her and I saw her suddenly catch sight of Edward and the others of us there. As we got nearer we must have been talking about her because she suddenly must have thought that this was one of the prisoners. She rushed, shouting with joy and embraced Edward, nearly squashed him to death. This was the charlady who had been starving in the days of Edward’s imprisonment.

MM: OK, let’s move ahead to your trips overseas, particularly with regard to any visits you paid in the Middle East and Far East. You have travelled very extensively. What countries have you visited particularly with Moral Re-Armament?

MB: Well I suppose we have spent the most time in India. I have been twelve times to India, from the first time in 1929. We have covered most of the Far East though I have never been in the centre of China. I have not been in Russia but with the different visits we have made we have covered a lot of the Far East. We stayed 6 months in Vietnam in two visits. We have made a lot of friends there and we saw what MRA could accomplish, given an open door. We have never forgotten our time there. It makes one realise, with these boat people now arriving in Western countries, how much people from Vietnam can bring to the national life of the nation they enter. It has not been brought out much in the news what their industry, what their energy, and above all their quality can give to the nations who give them shelter. Particularly this practice of listening to the inner voice. I think in planning for the relief of these people who have suffered so much it should be remembered what they can bring to us who need some of these qualities so much in the West.

One country which has interested me so much is India, with all the links with Britain. I am thinking particularly of the Gandhi family, Dr Buchman having been a friend of Mahatma Gandhi. Margaret and I were able to get to know his family, Devadas Gandhi and his family, quite well in Delhi.

Margie: On our second or third visit to Thailand in 1955, we met the Prime Minister of Thailand. At that time there was a musical called ‘The Vanishing Island’, which was going right around the world with about 200 people, not all in the cast but an accompanying group of very distinguished statesmen from different countries and leaders in different spheres. We went to Thailand, really to see if we could possibly arrange for it to come there, as it was in the Far East in Burma at the time we got to Thailand. We were told the Prime Minister was away so we rather thought ‘oh dear, well that’s a pity, we shan’t be able to get it invited to this country’.

However, we then heard he was back so we went to see him. Field Marshal Pibulsonggram. He had hosted an MRA conference the year previously in Thailand. but there were only five days between the time the musical was to leave the Philippines and the time it was due in Burma, so I thought it would be impossible at that short notice for it to go to Thailand. However, we went to see the Prime Minister and told him about the musical. ‘Oh’, he said, ‘where is it now?’ We replied that it was in the Philippines and would be in Burma after that. ‘Do you mean to say,’ he said, ‘that they are not coming to Thailand, they are not coming to my country?’ We said ‘no, not at the moment.’ ‘He said ‘Oh they must come!’ He immediately called in his aide. ‘Now look here,’ he said, ‘you have got to arrange for these people (I think there were 150 of them at that point because some had stayed behind in Singapore) ‘to come and put on their show The Vanishing Island in 3 days’ time.’ I just about went through the floor because I thought it was impossible because we had been told that there was a forthcoming Buddhist holiday, which meant two days’ holiday with the post offices closed and everything. I gasped and when we got outside I said to Mike ‘We can’t possibly do it, Mike, we’ve got to find beds for 150 people and all the invitations have to go out. It can’t possibly be done - all the feeding arrangements ...’ So Mike just laughed and said ‘Well you had better have a bit more faith. Why haven’t you got more faith?’ I thought he was a bit nuts and I spent a sleepless night that night.

Then next day we were summoned to a committee meeting to plan the whole thing. As we arrived I saw the Prime Minister’s daughter there and the aide to the PM. The PM’s daughter said she was taking on all the feeding arrangements and then it was announced that the PM had given two of his most beautiful guest houses reserved for important visitors for our people and that all the transport was being arranged by the aide, a military man. So there was really nothing else for us to do.

I asked what about the invitations to get the audience to the theatre which had been given to us, the Ministry of Culture theatre. I was told not to worry, that all the invitations would be taken round by motor cycle couriers - because there was no post. There was nothing more to be done by Mike and me, we just relaxed and waited for them all to arrive.

MM: Great stories from other countries. Now what about people from Britain, and Scotland in particular?

MB: Edinburgh is a great place for overseas students - there are a lot of post-graduate students here from Africa and from Asia, and many links with these people. We mentioned the Devadas Gandhi family in Delhi and Devadas was keen that his son Rajmohan get some newspaper experience. (Devadas was the Mahatma’s second son - Manilal who ran ‘The Indian Opinion’ in Durban, S Africa, and Devadas ran ‘The Hindustan Times’, the main paper in Delhi). His family were growing up and he wanted his son Rajmohan to get experience in journalism. Not being too keen on London he said to us ‘Do you think Rajmohan could have some training in Edinburgh?’ Luckily we knew some friends on ‘The Scotsman’ at that point who arranged for Rajmohan to have a year’s training as a journalist in Edinburgh. Then the next question was where would he stay - he had not been away from home before.

Devadas decided that he and all the family would come over to Edinburgh and see Rajmohan settled here. We got in touch with Dr and Mrs Petrie in Edinburgh, who knew MRA and who had had experience in countries overseas, particularly in the Middle East. They offered to have Rajmohan join their family here in Edinburgh. Mrs Petrie, who was also a doctor, came down to London to our home in London to learn how to cook vegetarian curries for Rajmohan. When the Gandhi family arrived in Edinburgh and we went round to the Petrie home, Mrs Gandhi - who realised that Rajmohan had never been in a Western home before to stay - as soon as she came into the Petrie home she said ‘I feel at home here, and Rajmohan will be happy here’. Rajmohan stayed there for a year and learnt the secret of quiet-times in the morning and applying MRA at home and in the office. He had a very happy year here with ‘The Scotsman’. That to me was another link with India.

I remember well my father and mother, who had never had Indians or Africans to our home, had the Gandhi family to tea and were so impressed with the courtesy and care that the Gandhi family showed that it made a great impression on them.

MM: What about Africa, and Southern Africa in particular.

Margie: We were invited to Rhodesia in 1975, the first time we had ever been there. We found ourselves helping to prepare a multi-racial conference at the University there to which people from all parts of the world were invited. It was a very remarkable conference. We didn’t have any money for it, I remember, in the planning of it, and we reckoned we would have to raise 25,000 Rhodesian dollars to help pay the fares of those coming from overseas who couldn’t afford all their fares and the general expenses of the conference. We actually had no money so we decided we would go round different firms and try and raise this money. One businessman said to us ‘You are crazy, all you will get will be £5,000’. However we took no notice of him and went on and we did raise the £25,000 needed. It was at that conference that many of the African militants changed their attitude, through meeting white people.

A group of men, black and white, met in Bulawayo. Really the idea came to them as they met and thought about the future of their country that a conference of this nature was what was required. There were many changes in the men concerned which led up to their even meeting together. One of them was Alec Smith, the son of the Prime Minister, who had undergone a very drastic change in his own life with an answer to drugs and the finding of a faith. He then wanted to be a responsible citizen of his country and began to make friends with some of the militant Africans such as Dr Gabelah, who was one of those meeting to plan this conference, the Vice-President of the UANC at the time These two men got to know each other and began to trust one another. Then there was a former white Cabinet Minister who made a very deep apology to an African lawyer who had had to leave the country because he wasn’t allowed to practice any more in Rhodesia. This man was in the Cabinet at the time and felt that he was responsible for this man’s exile. He wrote a very deep letter of apology to him. It was men such as these who had the idea of this conference.

MB: And the university was bound to be an ideal place because it was already a multi-racial university with indeed more African students than white. It was headed by the Principal, Dr Robert Craig, formerly of St Andrews, who has taken a real lead in movements of this kind.

MM: Now right to the heart of current events. Can I just ask you both now some personal feelings about the future. Do you face the future with hope or do you feel pessimistic about the world situation?

MB: I feel realistic. It is no good just having a vague hope about things. I think this new process of change will have to come, sooner or later, inevitably, if we are all going to survive. I see the Bank of England has appealed this morning for a change in attitudes by us British. I think this would be a very great encouragement to Zimbabwe-Rhodesia if they saw signs of change in Britain. It is also true that the change in men like Alec Smith has had a great effect on people. I think for our African friends, the black Africans have hoped for a long time to see a change of attitude on the part of the whites. This is happening, and you cannot stop it. Conversely many of the whites who have given their lives for Africa and in building up these farms which are feeding such a great part of Africa, they have hoped for a responsible attitude on the part of the blacks. This is also happening. Sooner or later I am convinced that this is going to prevail.

MM: It seems that there are many stories of individual change among black and white in Rhodesia, but in general it was not enough and not in time to prevent the war. It did not go fast enough, there were not enough people won and changed by this method. It seems as though it took the war and the suffering to force people to face the fact that change was essential. It seems that in the history of mankind it often takes great suffering to bring out the need for change and make people prepared to face it. Yet the story of MRA is a story in many cases where change has been given a new incentive, where a new inducement is there for change - do you look ahead into the future to see new initiatives, new ways in which this might happen?

MB: Yes, I think what you say is quite important because you cannot solve one particular local problem, however serious and however extensive, like Rhodesia, by thinking only of Rhodesia. I think a lot about Northern Ireland. You can’t live in Zimbabwe-Rhodesia without also thinking of Northern Ireland We tried to propose solutions to other places in the world and I know we are helping a great deal in some of them. We also have to remember that other countries look at us and think about Northern Ireland where we have not been too successful. I don’t think we will solve some of these problems if we only think in a self-centred way of the one problem. I think one of the first jobs in facing a problem is to put it in perspective. I think you have got to put up to people who are in a difficult situation a challenge of what they can do for the rest of the world. Then the perspective changes, and I am quite sure that would happen in Ireland. After all Ireland gave Christianity to the world in the early days. Couldn’t we, together, propose something so big to the people of Ireland and the people of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia that their perspective would change and their whole effort would go into solving some of the other problems in the world. I think this is why what you say about perspective is so important.

Kit Prescott has always been one of the men who has had an extra ration of faith, not only for himself but for others. As Margaret said, he was told to take an easier life after a heart attack and he set off for Rhodesia, him and Joyce. When we got there he was turning the place upside down. Of course, one of the people he got to know was Alec Smith who had just been cured of drugs by a real experience of Christ. As Alec said to us at the time, ‘I was in danger of being a dead Christian, and it was because of meeting Kit and Joyce and the others that I became a live Christian’. He had had this change through attending a church service and the minister preaching to him, but what was he to do then? Kit kept after him to keep changing and to change others. He took part intelligently in planning for Rhodesia and of course continued to live at home which made a great impression on his parents. I remember how Kit used to keep after him relentlessly to be effective and to maintain discipline - to such an extent that I thought ‘you will lose Alec’ with the challenges he put up to him. But he didn’t.

Kit had this same measure of faith for everybody. He and Joyce together were able to help all kinds of people, and when Joyce got back to London this last time she was able to go and see Bishop Muzorewa’s son at his hostel in London and keep up their touch with him.

Margie: Kit Prescott went and knocked on Bishop Muzorewa’s door when he had been in Salisbury a few days. Nobody knew him, so Kit thought he would go and get to know this man whom everyone was talking about. He went and knocked on the door and made friends with him.

MB: And all the white people we knew in Rhodesia at the time said ‘How do you get to know these people? How have you met them?’ Kit said ‘I went and knocked on his door’.

Margie: Many a time he and Joyce visited the home and they got to know his wife, Maggie, and made great friends with her. They never left the house without kneeling down round the table in the sitting room and praying together.

MB: When we were out there Kit said to us ‘You must come out and meet the Bishop’, so we all piled into a car and went out to meet the Bishop. A Russian grenade had just exploded outside the house shattering all the windows They were busy putting up a security fence and wouldn’t let us in to begin with. Finally they found out we had a date with the Bishop so the guy behind the steel door let us in and Mrs Muzorewa, Maggie, met us. The place was in chaos because they were putting in burglar alarms and security systems. However we got into the garden through the gate and there were 5 women down on their knees on the grass, so we asked Maggie and she said ‘Oh yes, these are our ladies here. We ladies find that unless we get down on our knees and pray the men do nothing. So if we want initiative on the part of the men we get down and pray together.’

Then we went into the house and I knew the Bishop had been with some of the journalists but a few minutes later he came in. A very small man in a tidy brown suit, came in and greeted us all very warmly, asked about MRA and our work generally, discussed the questions in Rhodesia. At the end of 20 minutes I whispered to Kit who was sitting next to me ‘Don’t you think we should leave now?’ because I knew another party of journalists had arrived. Kit replied ‘Oh no, we don’t go till we pray.’ I sat quiet and a few minutes later the Bishop made a move and we all went forward into the middle of the room where there was a round table with bevelled edges. We knelt down and prayed. The Bishop prayed for the world work of MRA and all of us. We prayed for various things, and we got up and left. The Bishop may not be perfect, but he is a man of faith and there is no doubt that he has set this policy of reconciliation. It was in carrying out this policy that his colleague was killed a few days ago, hacked to death, and it was that policy that Arthur Kanodereka was following a few months ago when he was assassinated. These are the realities of the situation in Rhodesia today.

MM: Do you think that men like Nkomo and Mugabe understand the forces that are behind such acts of gross brutality as that. Do they see them just as weaknesses and aberration on the part of individuals or do they see them as part of an ideological force that is out to use them and their movement?