An interview by Reggie Holme in the home of Paul Petrocokino, in Tirley Garth, Tarporley, in about 1979

Paul: On my father’s side I am Greek by race. My grandfather was the first to come over from Greece. He was in a responsible position in a textile industry first of all in Bradford, where my father was born and then Manchester, where he became president of the Greek community.

We came from the island of Chios which is, according to tradition, the birthplace of the poet Homer. Father, in some ways was more English than the English. He read the lessons in church on Sunday, hunted with the South Berks Hounds, was head of the British Legion, hunting, shooting, fishing, cricket - captain of the village cricket team. Nonetheless, as far as blood was concerned, he was as Greek as Achilles. There was a book produced called ‘The noble families of Chios’, written by Philip Argente who was Minister at the Greek Embassy, and our family - including myself - feature in that.

My mother’s maiden name was Sykes. Her father was Sir Frederick Sykes and her grandfather was Sir Francis Sykes. I think he was the man who built Basildon Park, a very famous Georgian mansion. He was a baronet, so you may say that I come from a somewhat privileged background and, you might also say that I have ‘blue’ genes on each side of the family. However you like to spell it, I don’t have any jeans, I am afraid.

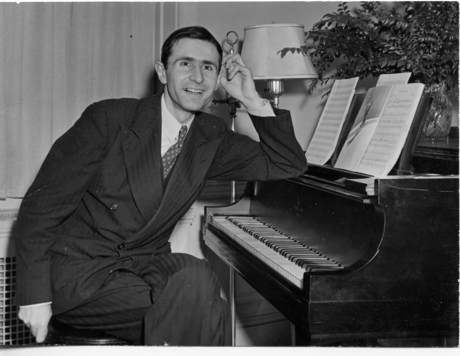

First of all I was at home because father was away at the war - the First World War. It wasn’t until I was 9 that I went to a preparatory boarding school, an excellent though strictly disciplined school at Harrow called Orley Farm, which still exists. I started off being dogsbody number one there and ended up by being head of the school and probably one of the outstanding pianists at that school. I established a record between being in the top form doing Latin and Greek and four forms down in mathematics. This was a science which baffled me absolutely totally.

After my time at Orley Farm I fulfilled a long-cherished wish of my father’s and went on to Harrow school where he had been a roaring success. He ended up as monitor, head of his house, in the school football team and captain of the house cricket team. I, on the other hand, was an almost total misfit there. At that particular time that great school was more what you might call ‘factory’ - the end product of which was an administrator of empire rather than an artist. I am by nature no administrator of empire or anything but am a pianist and composer.

It depended very much from one house to another house but to a certain extent it was true that artistic types were a bit sissy and the only people who mattered were those good at sports. It is not true now I believe. That doesn’t mean I wish I had been a cricket success. I would love to have satisfied that ambition of my father’s because it is a magnificent game and it is a frustration of mine that I was never any good at it.

The influence of my mother on me was absolutely terrific. Father was away at the war so I didn’t get to know him terribly well. Mother educated me, although I didn’t know I was being educated, to take a tremendous interest in all the things that were growing in the countryside, in the shells at the seaside and the weather - the prediction of which became a great passion in my life. It was really her sharing with me some of the things which meant the most to her. I owe an absolutely unpayable debt to her and if any people today say that family life and marriage is out of date and irrelevant, they can tell that to the marines. On one strict condition and that is that no marine bothers to listen to them because it is tommy rot.

RAE Holme: It must have been a terrible shock to you when you were 14 and got the news of your mother’s death.

Paul: One morning at Harrow I was sent for by the house-master. I wondered what on earth I might have gone and done now. He said to me ‘I am sorry to have to tell you that your mother passed away last night.’ She had in actual fact been dying of cancer for the best part of a year, though I didn’t know that. In a way the immediate effect was numbing and it seemed almost the end of the world. There were no immediate tears but my nose began to bleed, so the house-master sent me up to the house matron who rather precipitately leapt to the conclusion that I had been having a bash with another fellow and began to tick me off until she learnt from the house-master what had happened, then the poor lady was rather covered in confusion.

People were remarkably kind at that time but it did have the effect of rather undermining my security and making me a bit giggly. I kept giggling in the French form and the form master got the idea into his head that I was trying to create havoc and threatened to send me up to the headmaster. Fortunately a bout of ‘flu intervened so the next time I went to the form I had got over the giggliness and my most flattering report was ‘Less childish than of late.’

RAE Holme: What about your relationship with your father, because I understand when he came back from this shattering war your first request was that he should come up and see your new engine?

Paul: I was only 9 at the time and I think most young lads of that age might have done the same. By and large my attitude towards my father was of immense respect for what he stood for in the world. He was a magistrate and quite a public figure and in some ways a great man. He had travelled on his own from the source to the mouth of the Amazon. He could speak about 7 different languages - a good mathematician, unlike me, and also a man of strong faith. He was a churchwarden and it was more than a nominal thing. It meant a great deal to him. My attitude towards my mother was less what she meant to the world and more what she meant to me. I am afraid I rather used her as a supplier of my amusement and affection and so on.

I never had any question whatever about believing in the existence of God, even though the first prayers I learnt were somewhat of a childish character. I did not understand the words but I was quite convinced that there was a benevolence and enormously important being who took a lively interest in me and whom it would be unwise to cross too much. Then when I went to Harrow, a good sermon from one of the masters, or on one occasion the headmaster of Eton came and preached, and it would have an effect on me. I remember deciding to start saying my prayers which I did every evening and all of us did. I also started a time of quiet, in order to have a sense of getting into God’s presence. Now all these things gave me a sense of the difference between right and wrong but on the other hand did nothing to arm me with the power to deal with the wrong. When I was confirmed, after my mother’s death and just before my father’s, I really expected something big would happen to me. I asked the house-master ‘When I receive the Holy Spirit, does that mean I will have a new power with which to deal with temptation?’ I am sorry to say he said, ‘Oh dear, no old man,’ which was where he missed the bus because of course that is exactly what it does mean or it means one of these things. I never lost the sense of the difference between right and wrong but, on the other hand, I did not get the power to resist the wrong - which is the important thing.

I didn’t go straight from Harrow to Oxford, but had two years with a coach in Deal - from where incidentally I went once a week over to Canterbury and had piano lessons from the organist of Canterbury Cathedral. After these two years I managed to get into Exeter College, Oxford and very much enjoyed life there. There was a freedom to be oneself and not to conform as you had had to do at a public school. I welcomed this, while at the same time I was conscious of what nowadays one might call a permissiveness. It was an almost infectious sense of moral wrong knocking about the place and it must have permeated me. Mark you, it was already there largely in myself but there was again the pull between what I knew was right and the influence of my late parents. My father had also died while I was at Harrow. I could never go absolutely wrong with an easy mind, because I knew what they had hoped.

Then, by a rather remarkable coincidence, I came to hear of the Oxford Group which was the forerunner of Moral Re-Armament, in the following way:-

Watching trains was one of my great passions at school and it carried on into university life. I went to see one of my fellow train-watchers one Sunday afternoon and, while I was chatting about different types of locomotives, a fellow came in to the room and said to him, ‘Hello, are you going to the Oxford Group meeting tonight?’ So I said, ‘What is the Oxford Group, if I may ask?’ He gave a very interesting reply. ‘The OG are a group of people who aim to live continuously in the presence of God.’ Now that is a definition which might appeal to people with a religious background but might go like water off a duck’s back with somebody who hasn’t. Nonetheless it struck me very forcibly because I knew that on Sundays when I was due to take communion, it was quite an effort to put aside my natural self, with all its tendencies, for a stretch of about 36 hours before resuming them on Monday with a sigh of relief.

Living all the time in the presence of God, as I imagined the sort of bearded patriarchs like Abraham, Moses, Elijah and co did, was a new idea to me. It was not only a new idea but I saw at once what the implications for my thought life would be, for what I read, what I did, all before I went to the meeting - two years before. Something implanted in me the conviction that if I really wanted to be honest and bridge the gulf, the deepening chasm, between my highest ideals and the way I actually lived. These were the people who could help me do it, if I was prepared to pay the price. Nobody told me that, it just was an implanted conviction.

It wasn’t until two years after that various events transpired which led me to my first Oxford Group meeting. It was really rather amusing as a matter of fact. There was a particular undergraduate girl - at that time in Oxford’s history the majority of them were fairly sober, staid and scholarly. There was one lurid exception whom you used to see either walking with exceptionally high-heeled shoes, or else bicycling slowly down the main street of Oxford trailing a little black-and-white dog. We used to know her as ‘the dog girl’. Now I did not know this girl, but I knew a tough little man in our college who did. He was said to be safe to approach when sober though you were apt to get dotted in the eye if you approached him when he wasn’t.

One night, seeing him in the quad, and deeming him to be sober, I sauntered up to him and said, ‘Hello, seen the dog girl lately?’ He said, ‘Haven’t you heard?’ I said, ‘Haven’t I heard what?’ ‘The Oxford Group have got her. She’s gone Christian,’ he said rather mournfully. ‘Good heavens,’ I thought. If a miracle could happen to transform someone like that who I looked upon as merely a subject for a spot of gossip, then a miracle could happen to me also.

Now I am not prepared to swear that this happened but I am almost certain that it did. I would say my prayers every night as part of the process of going to bed. This time I think I added a codicil, ‘God, if you would like to put me in touch with the OG, this time I shall be prepared to go through whatever is entailed.’ The very next day I walked into the Common Room and heard two men having a strong argument about the OG, one for and one against. I latched on to them and I said, ‘I would like to go to the next meeting. When is it?’ And they said, ‘The Randolph Hotel, next Sunday evening. Come along’.

Some come along I did to the Randolph Hotel, to a meeting attended by about 300-400 people all of whom looked as though they were expecting something very exciting to happen when the meeting started, not at all like a religious meeting where everybody had long faces and artificial silence. There was a sense of expectancy and excitement in the air. Then the meeting started. I had heard rumours about the dangers of this work, so I didn’t know what to expect. A very sensible-looking chap, who I took to be a younger don, was in charge of the meeting and introduced a cross-section of men and women from the university life. What was clear was that they had found something which meant everything to them and in the case of families it had united brother and sister. Furthermore, there was a unity between them of a virile type such as one associated with the College Eight far more than the sort of rather sentimental fellowship that exists in certain religious circles. It was fellowship of men with a purpose.

At the end the Prof. of Psychology of the Christian Religion in Oxford at that time said how this work of the OG had helped him enormously in his own work. That was the end of the meeting. Two good colleagues of mine tried to discourage my further interest in it as we walked home. I couldn’t understand what their difficulties were. They said, ‘You don’t need anything more. You’ve got your music.’ But my music had not helped - wonderful gift of God though it was - build this bridge I talked about, between my ideals and the way I lived. All it did was when I heard an uplifting piece of work, such as Handel’s Messiah, it made me see the shabbiness of my own life contrasted with the magnificent purity of that work but it didn’t build that bridge.

What did build the bridge was that the chap who had asked me to that meeting asked me whether I would like to meet the man who ran the meeting in person. I said yes I would, knowing I was sticking my neck out a long way and that it was tantamount to enlisting in this work with whatever personal adjustments to my own life it might involve, no matter how painful or costly they might be.

As a matter of fact, before I had tea with this chap I had gone for a walk with a friend of mine, said goodbye to him at his lodgings, walked back to my own digs at Oxford and suddenly I decided there and then on the street that from that point onwards everything in my life which I knew to be shabby should go and should not be entertained. I believe it was St Augustine who said once ‘Lord make me pure but not just yet’. That was rather the way I had been but I decided now that the time had come. I went straight back to my lodgings, destroyed all unsavoury and doubtful pictures and literature and paid all outstanding bills as a beginning. When I turned in that night I suddenly had a picture of what my life must have been like, what grief it must have caused my parents in view of their hopes for me. I had a wonderful sense of sort of reunion with them, as well as with God. I still wondered whether I would have the strength to carry out the resolve but I was absolutely determined to do so.

Next came the tea party with the man who had led the meeting, a man called Roland Wilson who is still one of my best friends to this day. I was somewhat apprehensive, not knowing what it would involve, but we had a very nice tea in his spacious and gracious lodgings. During the course of the tea he spoke to me about the four moral standards which had been mentioned at this meeting - absolute honesty, purity, unselfishness and love. Then he suggested this:- he said, ‘I find it personally myself very helpful to start each day with a time of quiet when I ask God to show me what he wants me to do. Furthermore I was thinking of you in my quiet-time this morning.’ I thought that was jolly decent of him, I had never heard of anybody thinking of me in their quiet-time before. It associated in my mind with the idea of such a thing coming from a senior tutor or fellow, a chap roughly my own age who didn’t know me at all well to care enough, this struck me as something very new. It impressed me immensely, as indeed did his whole bearing.

He said, ‘I had the thought to invite you to a houseparty (an assembly over a period of a weekend or a week) which is taking place at Cambridge during the Easter vacation. I thought well ‘if God Almighty has suggested that Paul Petrocokino has got to a houseparty in Cambridge in the Easter vacation it would be highly injudicious of Paul Petrocokino if he did anything else.’ So I said, ‘Right, count me in.’ Then as he helped me on with my coat I said, ‘What I like about your people is that you show one how, you don’t just give one good advice.’

Next morning I experimented with one of these times of quiet. I was rather apprehensive as to what thought God would put into my mind but it turned out to be completely unexpected. Not all the thoughts one gets when one has times of quiet are completely unexpected and irrational like that, but it was ‘Go and see Major Porter’. He was the man who my father had appointed to be my guardian after his death and who lived in Reading, 20 miles away or so. I got into a train having made a date with him, went to see him, landed on his doorstep, told him why I was going to see him. He said, ‘Paul this is very interesting but I think the person you really ought to tell it to is Mr Ginzel.’ He was the General Manager of the small family business which my father had been the owner of and which Mr Ginzel had created into a working and first-class small business. Major Porter said, ‘Mr Ginzel is pretty ill and I think what you have said will mean a lot to him.’

I went round to see Mr Ginzel, who I always thought of as being a nice old josser but I never took the slightest responsibility for him. I told him my story. Now I wasn’t in the habit of talking to people about God but I discovered that this man was actually dying of cancer. I also discovered that he was fond of music. I had never known that before. After seeing him I nipped round to the music shop, bought him a record of excerpts from Handel’s Messiah, my favourite work, and brought it back to him. Then I went to see Major Porter and told him. He said, ‘Good. Another chap you ought to see sometime is old Alec Hopkins’ who had been the parson in the village where I was brought up. ‘He is pretty ill, he is in hospital.’ So I went to see the old parson, parson of my childhood, and told him. He said, ‘Thanks very much young fellow for telling me this. What I am going through now is pretty difficult. It tests one’s faith. You have helped me.’ Then I went back to the lower platform of Reading Station and as I stood there I thought ‘Great Scott! For the first time in my whole life as far as I can remember, I have actually been able to help somebody else.’ Then it occurred to me that this unexpected thought had revealed to me the fact that two men to whom I owed a great deal were both of them seriously ill and I was able to help them both. Had it not been for that, I would never have found out. They would probably both of them have died without my knowing a thing about it.

That was before I went to the houseparty at Cambridge, but God - as it were - was showing me that he was a person to be trusted and that if he did put the screws on a bit and ask me to do difficult things, he had a very good reason for doing so.

Then the time came for me to go to Cambridge, where I was received by Roland Wilson and where a great many people were gathered together. During the course of that time in Cambridge - to be specific, on April 8th 1932 - I moved from what might be called the experimental stage of seeing whether it worked and whether I liked it or not, to deciding to obey God unconditionally for the whole of the rest of my life - that his will and not mine should be the governing factor.

What this specifically meant was deciding to give the whole of my life to God, including the question of whether or not I married, and if so who. I had always somehow thought that the highroad to bliss was to find the right partner in life and the right partner in life was the one who happened to exert the most magnetic pull on me at any given moment.

Now at no point did I join a movement. Before I got on my knees and made that decision and made it aloud, incidentally, I would refer to the OG as ‘they’ and concede that they were doing a very good work. When I got up after my decision I referred to them as ‘we’. The enlistment was one of the will towards God and not the joining of a human organisation.

The enlistment was for whatever God might lead me on to or ask of me. Dr Buchman - the pioneer of MRA - was taking ‘behind-the-scenes leadership’ at this assembly. Most of the meetings were led by younger men. He took one meeting and in that meeting he gave a picture of nation after nation across the world, where there were groups and forces of people being built up who would live by Christ’s standards and under the direction of God. One began to see a world force for moral and spiritual regeneration. So I left Cambridge as part of that and not simply as an individual trying to be more virtuous and paddling his own canoe.

One decision I made, having faced these absolute standards, was to put right, by apology, every resentment that I had. The first was to write to my aunt with whom I lived after my parents’ death and to apologise for having been difficult to live with. I also said in writing that I had given my life to Jesus Christ. For some reason or other I found that difficult to do, but I did it. Also, by the way, to omit adding, ‘you also were difficult. I think you older generation need to understand us a lot better’. None of that. Just me, where I needed to change. It was as difficult to release that letter into the slot in the box as it was to write it but it rebuilt my relationship with my aunt and really gave her the gift - if you could call me such - of a son when she had none of her own.

Then there was one girl at Oxford whom I had hoped to marry and she had not responded. I took this as a personal insult and went around telling everybody I knew, ‘Thank God I got out of that frightful female’s clutches’. It wasn’t any such thing. My pride was injured. I wrote a simple letter to her, told her of my decision and, hearing that she had got engaged to somebody else, wished her the very best for the future and that was that. Immediately I got the warmest possible letter back in return. That was another humbling but necessary letter written and a relationship rebuilt.

I went back to Oxford to try and enlist other people in the same fight and began to see my fellow-students (though we didn’t call them students in those days, we called them undergraduates or something) through different eyes:- not how they would treat me, “this chap will be nice to me, I like this fellow, I don’t like that fellow, I am scared of the other fellow”, but what their potential influence for good was in the college. I would pick out the people who I felt could do most if they found the same answer that I had and I had a jolly good shot at giving it to them. Some of them were enormously impressed. Others were scared stiff. Others laughed a bit. The Rector of the college noted the fact of the vast increase in output of academic work that I did and the fact that instead of amiably drifting round the college quad chatting with my friends I actually got down and did a bit of work and began to pass examinations which hitherto I had been failing.

I was preparing for a Pass degree, first in Latin - which I thought would involve no output whatever of work and the avoidance of work was an important principle in my life at that time (this was before I met the OG). The second one was military history, which I wasn’t in the least interested in. The third - which I chose after my change at Cambridge - was theology. I passed military history and theology at the same time. Unfortunately the powers that be wouldn’t let me kill two birds with one stone simply by taking the book of Joshua! There it was. Before - failure. This time - victory.

Apart from compulsory lectures which were the term during which I made the decision - before that time I think I did a total aggregate of 2 hours work in the first 7 weeks of that term.

RAE Holme: You indicated that music was developing as a major passion in your life.

Paul: The chief change that happened to me was that I had the gift of being able to sit down at a piano and improvise, and improvise quite well as a matter of fact, though I say it myself. But what good is that? It is like water going under a bridge. What meeting the OG resulted in was that, when I created a bit of music, I had the discipline to sit down and write it out so that there it would be, both for myself and for other people. Also it was more of a recreation from that point of view than a life’s calling, as I saw it. Although I did believe that music was always meant to have a part and that I could refresh the spirits of other people by playing, I didn’t have any specific objective for it. The only training I had had was piano lessons and I, for some reason, have always had a passionate love of Baroque music - music written roughly between 1650 and 1760, you might say. Incidentally most, if not all, the composers of that particular type of music, even though they wrote during a phase of history which is known as the Age of Reason, were actually men of faith. The men of Reason produced fairly petty works of art compared to the masterpieces of the great Baroque composers.

Pablo Casals, the 20th century cellist, felt that true music must do more than satisfy the intellect. It must satisfy the entire heart. It must be simple and it must be comprehensible. I think my music is both simple and comprehensible.

When I left Oxford I was invited to work with Dr Buchman, starting off in London at a time when the city was incredibly grubby and noisy. I found it quite a difficult framework in which to work. Over weekends occasionally I was able to get into the wonderful county of Kent. Then I would come back with music singing in my ears as it were, which I then had the discipline to write down. Out of that came my first major work, which is known as the Kentish Suite. People who hear it do feel that is transports them into the countryside of Kent, ending up in the majestic cathedral of Canterbury, which I feel is Britain’s noblest building.

This campaign in London was inaugurated by our being ‘commissioned’ by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Lang. I was very impressed by the sense of being in the presence of a true man of God. He of course was the Archbishop who at the time of the Abdication of Edward VIII, stood firm and upheld the principle of the sanctity of the home and would not go along with a broken home being the centre of British national life. The result of his decision was unforeseen but it meant that we had one of the finest Kings and Queens we have ever had on the throne and of course the parents of the present Queen. He came in for a lot of criticism by people who don’t think or, if they do think, they think the wrong thing. He realised that Christianity had a moral backbone. That was why he said publicly, at the time when the OG was coming under fierce attack which it did from sources ecclesiastical and other, that the OG is doing what the church of Christ exists everywhere to do. It is changing human lives.

The attacks consisted of hostile letters to the papers. Some came from hidebound theologians who - if you did not stress certain evangelical truths in the way they thought it should be expressed - suggested that you weren’t Christians at all. Others came I think from what today we would call ideological sources. Way back there were forces at work in the world, possibly going back to Lenin in 1917 taking over Russia, but forces at work who wanted to undermine the moral fibre of the leadership of the free world, and particularly at that time of Britain and the USA. The way you take over a nation is to get a generation that cannot say no to itself, a generation which is indifferent to issues of right and wrong, not just social issues of right and wrong but personal, moral issues of right and wrong. Frank Buchman standing firmly for absolute honesty, purity, unselfishness and love as a prerequisite for leadership in the life of the country, cut right across the plans these forces had. They would then use gullible clergy or people who had moral Achilles heels.

There were people in the media too at that time who attacked us but it was a stand on moral issues which cut across these ideological forces. At the same time of course if you hear of somebody who has felt they were dishonest and has paid back money they owed to somebody they owed it and said why they did it, well everybody who hears of that who has done the same thing but has not paid it back, gets an uncomfortable itch in the conscience. You then have to do one of two things - either prove that the people who roused the itch are a bunch of hounds or else fork out, pay it back and eat humble pie. Simple things like that cause opposition too.

RAE Holme: What about attacks from the other ideology that was rising up in this time, the 1930s, the ideology of Hitler, National Socialism?

Paul: That came to the fore later in the 1930s when Ludendorf ran a newspaper and said that the sweet poison (of MRA) is finding its way inside the Third Reich and must be stamped out, or words to that effect. Later, during the war, the Nazis incarcerated and tortured and in some cases killed, leading figures in MRA in the countries which they overran because they stood for things which would make a country’s spirit impregnable.

This London campaign which I was invited to join straight after Oxford was to be launched by a very big public meeting indeed, which had followed a highly-successful campaign by Dr Buchman in Canada in 1932 and 1933, of which I had not been a part. Invitations by the hundred were being sent out to people to these meetings. Some of us young people were sticking on the stamps and addressing the envelopes. Dr Buchman came in, saw the way we were doing it, and he said ‘You are not going to like me much but you will have to do the whole lot of those again.’ The stamps were on crooked and the addresses were on crooked. For him an envelope had to - by the very nature of its presentation - compel the recipient to treat it as one of the first to be opened. That was my first touch with Dr Buchman’s sense of the need for whatever was done to have the stamp of God about it in its perfection. No sloppiness.

The second Canadian campaign followed this London campaign and he asked me to join it which was a great honour. After an absolutely fiendish crossing of the Atlantic we arrived in New York and then went up to Canada. There at Toronto we met hundreds of people who had actually enlisted and given their lives to God the previous year. The first thing we did was to shake hands with them. Canada at that time was known as the Dominion of Canada. I thought that just meant a dominion, part of the British Empire but Dr Buchman pointed out that the man who chose the name ‘Dominion’ of Canada did so because in the 72nd Psalm it says ‘And He shall have dominion from sea to sea’. The idea in the mind of this man was that Canada would be a nation where from Atlantic to Pacific people would live and things would be done in God’s way. Canada had a fairly small population at that time, as well as being an enormous country. So it was perfectly feasible to make that possible. In fact the Prime Minister of Canada at that time said, at a luncheon which I attended, that the work of the OG had been felt in every town and village of the dominion, making the task of government easier. It interested me that Buchman thought in terms of bringing a new spirit to nations, of changing their mental climate.

The following year Buchman went to some of the Scandinavian countries, where there was much cynicism. You had a pious older generation and a materialistic middle generation, who kept up some outward signs of faith but didn’t live it. Then there was a rebellious and atheistic younger generation. There too hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people started a new life, faced the absolute moral standards and God became a reality. In The Spectator - one of Britain’s most reputable and reliable journals - there was an article which talked about the miraculous change in the mentality in Norway at that time. Later, after the war, a Norwegian Bishop attributed the healing of the violent split inside the church, between what you might call the progressive and the conservative elements, to the OG. This healing had enabled them to form a united spiritual core to the nation during the time of the Nazi occupation.

Buchman was in a way completely unpredictable. You couldn’t say ‘he will work in such-and-such a way’ because he always sought God’s direction in what to do. One thing was interesting - his intense interest not only in people whom he saw clearly with almost x-ray perception, both their potentialities and their defects, but also nations. He always cherished the hope that a nation would become as distinctively run by God as, shall we say, Russia is run by communism. He would cherish a nation - he would make you see the best things there were to see in the country. He would introduce you to the sights of the land, the history of the place, the customs of the people. He was appreciative. At the same time also he saw the tendencies. For example, in one of the Scandinavian countries, Denmark, he said, ‘They are charming and hospitable people but they are under the influence of an atheist philosopher called Branders’ who started two newspapers. He named them and said ‘They have created in Denmark a cynical attitude so you have that to face when you deal with people.’

I think the miracles that happened in Denmark were a straight answer, because a radical change in a person’s life is unanswerable. Radical change in peoples’ lives was the thing Buchman constantly expected. He expected all of us to produce it, or rather to be God’s instruments in producing it.

He liked publicity because he wanted the millions of the world to know that God’s answer was available. He had an interesting expression, ‘Normal living’. By that he did not mean the way everybody lives, the commonplace, the accepted way of living, but the common-sense way of living. To him to live by God’s moral standards, in Jesus’ words ‘to seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness’ and to apply that to personal and public life, to give all one’s resources and whatever one has for that end, one’s position, one’s capital, one’s income, that is the way the human race is meant to operate. In fact the only way it can operate and survive. A quick look at the TV pretty well any day or night when the news is being broadcast just underlines the truth of what he said.

Buchman was sometimes accused of going after and making a dead set for prominent people. Certainly he did exactly that, because he wanted people in a prominent position to use that position under God for the service of their nations. It was in no way to advance his own prestige or position. I strongly suspect that the motive of the people who launched that particular accusation was a sense of acute jealousy themselves. However, to Dr Buchman anybody was an important person, from the waiter at the hotel where he happened to be, or the saddle-maker in Denmark I remember who spoke from the platform at a gigantic meeting in Hamlet’s castle. Buchman’s principle was to treat everybody as a royal soul. That as a matter of fact did not exclude, strange to say, royalty because he felt that royalty under God had an enormous potentiality for good.

One aspect of the work of the OG during the 30s was the annual summer houseparty in Oxford. Each year thousands of people from all over the world, and most particularly from Britain, would flock to these houseparties. In 1933 I think 5,000 people were present. After this second Canadian adventure an even bigger houseparty took place and I remember the way Buchman introduced it when he presided over the first meeting. One of his slogans was ‘I like fresh fish for breakfast’. By this he meant that if someone has been newly enlisted, don’t wait until they are fully trained and fully experienced before they have a chance to give what they have got to give. Let them give it and in giving it they will get more themselves and at the same time be helping a lot of other people. One of the men brought back from Canada with us on this occasion was a hard-boiled journalist from Vancouver. This man was put on by Frank to open the innings at the first meeting. He told a story which I will never forget. One of the bonuses you get in working with MRA is the amazing number of side-splittingly funny stories. This one from the journalist from Vancouver somehow touches me on my funny bone.

He began addressing the August assembly by telling the story of two elderly ladies who went out to dinner - a thing they didn’t often do. They went out to the restaurant. One of them said to the other in a rather querulous voice, ‘Dearie, these beans are dreadfully stringy, aren’t they?’ The other one said, ‘I don’t think they are so bad, duckie. Why don’t you try taking your veil off?’ I think he drew from that the moral that if the world seems to be a bad place and in need of change, the first thing to do is to start with yourself.

Another very interesting thing that happened at that houseparty was how the head of an Oxford college, unquestionably the most distinguished theologian in Oxford, if not in Britain at that time, was a Professor Streeter. He later became Provost of Queen’s College. In those days patronage and approval of the OG was by no means a rare thing, any more than criticism and disparagement of it was. But identification - I am part of this force - that required some heroism because it was always greeted with derision and in the case of an intellectual man, his thinking powers would be questioned. This man, Prof Streeter, blazed many new trails and made faith live for the younger generation who used to flock to his lectures. He said that he had decided to no longer give a judicious mixture of criticism and encouragement from the towpath but to step into the boat and start pulling an oar, because he found that the OG were being used by God to make more bad people good and good people effective than any other agency he knew.

Streeter was married to a very strong-minded, domineering you might say, lady whose theological views were diametrically opposed to his. In fact she looked upon her husband as a bit of a heretic. Meanwhile a retired headmistress had won the friendship of Mrs Streeter and had brought her to a new experience of Christ so that, instead of having a cast-iron theological point of view and a possibly equally cast-iron heart, she became a humble woman and became united and reconciled with her husband. As a united couple they were able to take on the leadership of their college before they were both killed a year or two later in an aeroplane accident in 1937.

It was after the Scandinavian campaign in the summer of 1935 that we went to Geneva. During the time in Geneva a very important turning point took place in my own life. It was suddenly borne in on me as I was out for a walk one afternoon on the hills behind Geneva that I was by race Greek as well as British and the heritage of Greece was mine. I then conceived a longing that Greece should again find glory in the world. They talk about the ‘glory that was Greece’. I wanted it to be the glory that is and will be Greece and I had learnt classical Greek - pronounced in the usual English way with total disregard for the rules of accentuation in English schools. I tried to teach myself modern Greek which has the same accentuation rules and gradually mastered a bit of it. From that point onwards the Greek world and the Aegean world, has had a major part in my thinking, my living and my praying.

Frank Buchman did me the honour of including me on a very small team that he took with him to Greece in the February or March of 1938. It was a moment of the greatest excitement when first I crossed the Yugoslav-Greek frontier and there by the platform were the Greek soldiers marching up and down with their marvellous kilt, the adzones. The name of the station written up in exactly the same Greek letters as you would find in a classical book. There was the moon shining and a rugged mountain scenery. It absolutely stirred my blood. I shall also never forget the occasion the next evening when I walked out with a friend of mine, Paparigopoulo - we specialise in these short names in Greece. He and I came on the magnificent columns of Olympian Zeus. Mark you they were built by the Romans, but still they were magnificent columns. Behind them were the dark flame-shaped cypress trees and against that the silhouette of the famous mountain of Hymetus, then a full moon. This mountain was famous in classical times for producing honey made from thyme and it still does. Then you turn round the opposite direction and there, floodlit by the moon, was the Parthenon. It was a moment I shall never forget in all my born days.

Much of my time there was not as happy as it might have been for two reasons. One, I was running a temperature, because you have to watch out it can be jolly hot on one side of the street and jolly cold on the other and you can cop it if you don’t watch your step. I had a light form of ‘flu a lot of the time. Also, I was feverishly trying to win my way back into Frank Buchman’s good books, having made some rather major bloomer the summer before and been sharply rapped over the knuckles. Very salutary really. The one thing you cannot do with Frank Buchman is to try to please him, because what he wants you to do is to try to please God. If you try to please anybody else you actually miss the bus and infuriate him. I had a time of only mixed joy at being in Greece and I rather missed the countryside of Kent and of England with its greenness and so on. The funny thing was that a timebomb was lit in my spirit and afterwards when I went to America to Los Angeles I saw the same kind of sun-baked hills and the same kind of pointed cypress trees, olives and things. Gosh I felt at home.

Now when I see those typical Mediterranean things, olive trees, cypresses, sun-baked hills, I feel I have come home as much as when I am in England. I got to know Greek people both in America where I was from 39-46, and then again in 48. I made a point of getting to know as many Greek people as I possibly could and doing my best to win them to the idea of listening to and obeying God. Mark you, with a Greek - and I am one - they say God gave a man two ears and one mouth why don’t you listen twice as much as you talk? Sometimes I am afraid that what we Greeks are doing when one man is talking is thinking what we are going to say as soon as he shuts up, so that is quite a point.

There are wonderful qualities among the Greeks, of hospitality and courage. I visited Greece later after the war years and was able to help in the translation into modern Greek of Frank Buchman’s speeches. Then I went to Cyprus, which was at that point a bone of contention between Britain and Greece. Britain and Greece have a tradition of deep and abiding friendship and the names of men like Lord Byron are venerated enormously. Byron gave his life for the cause of Greek independence. Also Britain and Turkey have a similarly strong relationship of friendship, interrupted only by the First World War.

When I revisited Greece, I took part in helping to train a group of students from Athens university, some of whom were Greek and others of whom were Cypriot Greeks, and to give them some of the type of training that I had received when I enlisted in MRA at Oxford. I also began to develop another passion because one of the miracles of modern history, the magnitude of which for some incredible reason the world has absolutely failed to realise, is the reconciliation between two nations which were historic enemies. If you ask the citizens of one nation who their enemy was they would promptly name the other. I refer to France and Germany. Now one takes it for granted that they are partners in Western Europe but that is a story told elsewhere. I began to conceive a longing that the same outbreak of God-given sanity which has united these two powers in Western Europe should take place between Greece and Turkey.

When I went to Cyprus I met Cypriots, both Greeks and Turks. Before I went to Cyprus I fully supported the idea that Cyprus ought to be united with Greece. I felt it was monstrous that nations in Asia and Africa should be given their freedom while a Greek country should be maintained as a colonial subject. However, I had not met the Turks then. When I met the Turks in their own homes I realised that they were Turks and that it was equally monstrous to think of coercing them to become part of Greece against their will. Now there is a picture of tragic division but what I long to see is for a bridge of forgiveness and understanding and creative cooperation between Greece and Turkey and for the Greeks and Turks of Cyprus to live together as brothers and not as enemies. The Greeks feel a natural bond of blood and of culture with Greece and the Turks feeling the same with Turkey, but the need is for them to forgive each other the wrongs that they have inflicted on each other and realise that they belong to an Eastern Mediterranean community.

I was tremendously honoured to be received with my wife in Turkish homes as a guest. I think of one home in particular belonging to a retired Turkish headmistress with her sisters. Now this Turkish headmistress had visited the MRA training centre in Caux in Switzerland in the early 60s and had come back from it and visited 150 Turkish villages in Cyprus and had told them of her experiences and of the absolute moral standards and the guidance of God. Then when inter communal troubles with their violence broke out in 1963, word reached me that this lady’s home had been burnt by the Greek Cypriots. This cut me very deeply because I knew she was a friend. So I wrote her a letter to which I did not get a reply, but the letter said roughly this: that I had been deeply grieved to hear the news about her home and that I wrote as a Greek asking forgiveness for what had happened, and that I would rather that my people were to endure a wrong than to inflict a wrong. As I say I did not hear from her but I heard from a friend that my letter had meant a great deal to her. When in 1973 I revisited Cyprus with my wife we were most warmly received by this Turkish lady. The last thing that happened before we went to the airport was that we stopped in at her home to say goodbye. She pressed into my hands a bag containing the most marvellous almond cakes which make your face all white when you eat them. Absolutely delicious! She had cooked them as a farewell present.

The following year I was in New Zealand. I had written to her saying that I hoped she was all right and had survived the troubles - the fighting, the landing of the Turkish army and so on - anything could have happened to her. I got such a warm letter back saying my letter had reached her safely and that thank God she was all right and she looked forward to the day when peace would again return in Cyprus.

She is not alone. There are others of the Turkish community who feel that way. And the Greeks too, most emphatically.

How did the course of true love or otherwise lead to a wife? In the following way:- First of all the decision that God, and God only, would give me the instructions to get married. If he didn’t then I would stay single, whatever my inclinations to the contrary may be. Different women attracted me in different measures and I would wonder from time to time, ‘Is this the one or is it not?’ and generally a clear direction would come from the mind of God to me. Once it came in the form of a quotation from II Timothy, ‘No soldier gets entangled in civil pursuits. His one aim is to satisfy his commander.’ So that put paid to that one. Which was a red herring anyway.

There was one girl who I frequently used to notice and for some reason or other I couldn’t quite say why. The way I felt about her was quite different from any of the others. I thought, ‘Gosh she is good fun to be with, I like her.’ Nothing much more than that. In fact my money, as you might say, was on another horse most of that time. On one occasion I was at an MRA conference in Michigan and the one whom I thought my money was on left to return to Canada and that was that. Then this one, Madeline, left to return to New York and suddenly the place where we were at Mackinac seemed to become just that much colder. It was as though part of me had gone. It was a strange thing.

Then much later on, about 1944, I was in Virginia, having just worked out a charter for farmers with rural people there which went right through the United States and Canada, called the Farmers’ Charter. This Charter pointing out the farmers’ place to provide not only food but faith and character for the nation. I was out on this farm walking alone and I asked the Almighty, if he wished to tell me - because being Almighty that was up to him whether he wanted to let me know or not - if I would ever get married. Of course, he being God and me just being a human being, he didn’t have to say anything. Very clearly into my mind, in a way almost unexpectedly came the thought, ‘You will marry Madeline’. Just like that. At the time it came, I knew that it was guidance from God.

Later, I began to think that it was probably my own wishes or something but it had a sense of rightness and from that point onwards we seemed to be thrown more and more together. A bit later I was working with a group of educationalists on Mackinac Island and some of them said to me, ‘Paul I think you have got this ideology more in your head than in your heart’, which I found a bit exasperating. Inwardly I thought they were silly goofs because even if I had it in my toenails it wouldn’t matter so long as I had it. Nonetheless they felt something, so I prayed and asked God to tell me what the new thing was that I needed. I had the thought to have a chat with one particular fellow - a very warm-hearted man called Roger Hicks, a confirmed bachelor himself but a great-hearted man and a true confidante. I told him this thought I had had about Madeline. He suggested to me the thought of beginning to care for her and take responsibility for her and think for her instead of just thinking of getting married to her. In the past I had always sort of thought about securing for myself the ideal partner in life, not in terms of what I could give. Another good friend of mine, who served in the American army had this thought, ‘Never mind how she feels. Love is a one-way street. All give, no get.’ I have remembered that as a principle and would recommend it.

Nothing was finally fixed between us until I returned to Britain. It was a sad moment when we left. I remember my final words to her as the boat was about to go out and we lined up on the dock to say goodbye to our American friends, those of us who had been over in America during those war years, most of whom had served in the army. I was actually rejected on physical grounds. I remember my final words to her were, ‘In the words of General Macarthur “I shall return”.’

The next spring I had the thought to launch an intercontinental ballistic missile in the form of a letter of proposal, which I duly did. Now it was an interesting thing - I had actually talked this matter over with Frank Buchman and had a wonderful heart-to-heart talk with him. He did not aim to control or regulate the lives of the people who worked with him, but in a family - and we were a family - it was normal to have a word with the father of the family. So I did. It was an extraordinary experience when we talked about it. He said, ‘Well let’s listen’, by which he meant be quiet and see what God has to say, because what he was interested in was whether or not I was in touch with God.

He had a quality about him that was like litmus paper. He could tell and it was funny - it was like sitting in the presence of a man who was a mixture of being a radio receiving set, in one way impersonal and at the same time a most warm-hearted father who wanted the thing that was right for you. Not necessarily what you wanted, not necessarily what you didn’t want but the thing which was really God’s destiny for you and would therefore be the most satisfying.

At the end of it he had the thought, ‘This is of God, foster it.’ I had the same sort of idea, that it was right. As much as anything I was grateful for having this heart-to-heart talk with Frank because to have a genuine father’s care for the number of people he had is a superhuman thing. In no man have I known the essence of Christianity in quite such a degree as I did in Frank Buchman - God coming to reside in the human spirit.

Now the time came to launch this letter. So I launched it and I had to wait a fortnight before receiving an answer. We had been in correspondence and that way had got to know each other. Finally one happy day on the 24th May 1947 I received a cable. My friends had warned me that a ‘no’ would probably be in the form of a letter but if I got a cable it would probably be an affirmative. I was told there was a cable from New York for me, so I said, ‘Good heavens, let’s have it’. I ripped it open and it said ‘A million times yes, much love, Madeline’. I yelled ‘Good gravy I am engaged!’ and so I was. Then I went over to America and we were married, in the heart of the conference at Mackinac, with hundreds and hundreds of people there. I have never shaken hands with so many people in such a short time. A marvellous partnership was launched between us which has endured and got fresher ever since. It is wonderful the way Madeline has identified herself with England, becoming part of England, while totally keeping her own identity. She has also given her heart to my Greek friends and, as a matter of fact, has also begun to take on board one of my greatest passions which is a love of Handel’s music.

There is a saying that marriages are made in heaven. Well they are if you let God decide who is the partner. If you married on any other basis, well redemption mean that you can still hand the thing over to God and let him renew a marriage so that he becomes the head of the family. I have the security of knowing that I am married to the woman God gave me, and it has been a wonderful thing.

We don’t have any children but none the less there are a great many younger people who mean a great deal to us. Both of us as a matter of fact come from a rather similar background of privilege. One of the things we have in common is that we have decided to give what we have rather than use it for ourselves - money as much as anything else. She also has some and she gives most regularly, most generously.

With special thanks to Ginny Wigan for her transcription, and Lyria Normington for her editing and correction.

English