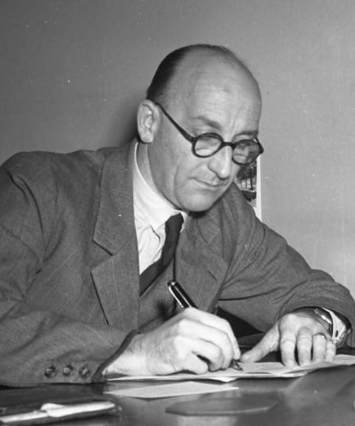

RAE Holme: I am at Tirley Garth and talking with Mr John Nowell , who was General Manager and Director of one of the largest sole leather tanneries on Merseyside. Later Mr Nowell became President of the Cut Sole Association, and was for 21 years Chairman of the Leather Institute, which he himself founded. This Institute had a budget of £250,000 a year. But to start with I would like to ask Mr Nowell about his early days, his family and his school days.

John Nowell:

Well my father was a Methodist minister and there 5 of us children. He was a man of very simple faith, which I always thought naive, but my parents lived a quality of life that we children admired, all of us, and wanted. They were united in heart and mind and we never heard them quarrel. But there was discipline, and sometimes stern, but it was never unjust. And I remember that we used to have to do certain things in order to earn our pocket money. We had every day to fold our night clothes, brush our teeth, clean our shoes, and walk round the dining room table with a dinner mat on our heads six times, and if we did this every day without missing we got a penny a week.

It is a discipline which has remained with me all my life. My mother was very - a stickler really for tidiness, and the slogan was ‘A place for everything and everything in its place’ and that really has remained with me through my life.

I started in the village school where my father was stationed at that time, along with all the village lads, and then I got a scholarship to the Plymouth College where my father next moved. And there I studied Latin and Greek, amongst other things, as my father hoped that I might become a minister. However my mind was more on the professions. I wasn’t inclined to be a minister. Then my father moved up to Runcorn, which to us children was a terrible move in comparison with the lovely surroundings in Plymouth. But there I found that it was very difficult to get a job of the kind that I wanted. So finally my father spoke to a member of his congregation who was one of the leading tanners in the country, whose tannery was in Runcorn. He asked him whether he could do anything for me. So the man told me to come along and see him.

And then he told my father, ‘I will give him a start. Tell him to come along at 6 o’clock in the morning, put on his working clothes. I don’t think he’ll be much good but at any rate I’ll give him a chance.’ And that is how I started.

I was put on to a job where the man was out for that period of time, and it was handling heavy hides and wet vats. It was something that I had never anticipated. I wondered whether I would ever stick it. The family didn’t think I would stick it. You certainly in a tannery need a sure sense of tread and a poor sense of smell, as you walk along the deep pits with the tanning liquor. However I felt that I needed to make myself knowledgeable about the whole process of tanning and so I was instrumental in starting a course of tanning classes at the technical school and so every night from 7 to 9 I would go there for chemistry and tanning, and so we moved on until the time of the First World War.

And then I joined the Pals Battalion - the King’s Own Liverpool. They were young businessmen mostly and professional men. The training however was by the Grenadier Guards and was too severe for me and I got middle ear trouble with the result that I was discharged from the army which I thought was a terrible thing. My doctor operated and by the time I was better the leather industry had become a protected trade because the leather was required in vast quantities for the armed services.

One day the boss called me and said, ‘You are not doing much good. You are not pleasing me particularly.’ I said, ‘I am sorry. I am working in two departments now.’ Yes, but I want someone with initiative, I can get anybody to do what you are doing at thirty bob a week. I think you had better go and see Mr so and so (who was the head of Sales).’ So I duly went to him, and he said, ‘Well you had better try and sell leather.’ He sent me into a district which was known to be very hard and difficult. And that is how I launched onto the what one might call managerial side of the leather industry.

Whether it was beginner’s luck or not, the first man I called on gave me a good order. He hadn’t done business with us for many years. So I gradually built up business. This really happened just before the war, and when I came back from my short service, there was no need to sell leather at all and it was simply a question of producing it, so that I became much more concerned with the production for the next 2 or 3 years. And then there was a very serious fire at this tannery at which I was working, and the drying sheds were very severely damaged, much of it wiped out. So an old derelict soap yard existed in the town, and was taken and adapted for drying the leather. And there I went and helped to oversee what was being done. Finally it was decided to form a separate company at this place, and to concentrate on the production of sole leather for the manufacture of women’s and children’s footwear, a market which had been captured by the Americans. Thousands of tons came every year. I felt I needed to learn just why it was that this leather was so popular and so I spent a fortnight of my holidays in a shoe factory, to discover exactly what they did with the leather, and what qualities they looked for. And then in consultation with my production colleague at the tannery we did begin to produce a leather that became very very popular and became indeed the most popular leather for this particular work. And we succeeded in capturing the trade.

We were very successful and in the next ten years or so we increased our production ten times. And were considered a very successful and also as we thought a contented tannery - amongst the workers.

I was a very active church member, holding many responsible positions, and also a lay preacher. In fact I thought I was no end of a good fellow. But not everybody did, apparently as my sister gave me a book called ‘For Sinners Only’. I wondered why on earth she should want to give me that. And I read this and it talked about absolute honesty and a few things like that. I thought, ‘Well this is no good to me, you can’t do this in business’, and so I turned it down flat.

Well then a little while after that I went to see my cousins in Wilmslow, the other side of Chester, whom I didn’t often see and there were two fellows - my cousin was younger than I was and was tinkering with a car - and after they had cleaned up and we sat down to tea they suddenly said to me, ‘Have you got an Oxford Group at Runcorn?’ I said, ‘No thank heaven. We have got a group who meet for prayer and things like that, but we don’t want the OG.’ Well then they began to tell me what it had done for them, and how it had changed their lives and how they had found a real experience of what true Christianity was. And I knew as an orthodox Christian that what they said was the real thing. And I thought, ‘Now this would be very good for the young folk in Runcorn.’ So I asked if they would send over some young folk and come and talk to ours. So they agreed, with pleasure. We did that, we got about 50 young folk in our home and they came and talked to them. I thought it was rather naive, what they said, but one thing I couldn’t get away from and that was the quiet time as I knew there was all the authority of the saints of the ages for doing that. And so I began to listen too.

And then certain funny things happened - or they seemed strange to me. A fellow that I didn’t know and who lived in Runcorn and who was also a lay preacher, was accustomed to going on hikes on his own and set off one day to the south of England and on his way back he was coming through Oxford. And sat by the roadside footsore and weary wondering whether he would make it, when a car pulled up and offered him a lift. And he said he would be very glad to be put down in Oxford, near a cafe. So he was put down by a cafe and was just standing wondering what he would do when a fellow dressed in camp attire came up to him and asked if he could help at all. This Runcorn man said, ‘I don’t know whether you can - I just was wondering what I was going to do tonight, where I would spend the night.’ Well the man said, ‘If you are free and have got nothing fixed up I could find you a bed tonight. There is a very interesting camp just outside Oxford, a whole lot of fellows, international, meeting together. They are really considering what they have to do and how they have to change in order to change the world.’ So the Runcorn fellow said, ‘I have not come out to go to religious functions - I have come on a holiday!’ So the other man said to Jack, ‘Well come in here and let’s have a cup of coffee and talk it over.’

Then he told him, ‘Every morning I listen to God, and this morning it came very clearly to me to come down to this cafe at this time and I would see someone who was in need of help, and I could help him. So I have done that, and I am asking you whether you would like to join.’Well this so intrigued Jack that he decided that he would go to the camp. After they had had their evening meal they sat round and began to talk and then someone suggested ‘Why don’t we have a time of quiet and just listen to see what God may have to say to us?’ So after a little while they began to share what had come to them and turned to Jack and said, ‘Did you get anything?’ He said, ‘Well I just got a name - John Nowell.’ ‘Do you know him?’ ‘No I don’t know him. I know that he is a well-known figure in Runcorn and is a lay preacher like me.’ ‘Well you had perhaps better follow it up.’ So Jack went out of the camp that night into the fields, as he said, because he couldn’t rest. And there he had an experience of the cross which he had never had in his life before, which brought some radical change to him. He felt a new man, a new freedom, a new release. When he got back to Runcorn he went straight to his minister and told him what had happened and said, ‘What do you think I should do?’ And the minister said, ‘Well, there is a fellow, John Nowell, whom I know is interested in youth and why not go and see him and tell him?’ Which Jack did. And this shook me considerably.

So from that time on I began seriously to listen in the mornings, to see what God had to say to me, and the one clear thought that came again and again was, ‘You can never start to put yourself right or the world right or the works right until you are honest with your wife and your family.’ Well, that I refused to do. I couldn’t face that. And then there came to see me a young fellow who was the youth leader at a local Anglican church and a research chemist in ICI, and he said, ‘I have come to see you because I am in a mess. I seem to have lost my faith and I have lost my affection for my wife and my children, and I just don’t know what to do.’ I said, ‘I can’t tell you, but I do know that if you listen to God and are determined to do the thing that he tells you, you will find the answer? Why don’t we just be quiet?’ What came to him I don’t remember now. But what came to me was quite clear ‘Until you have been honest with your wife and your family you will never help this man or anybody else.’ And that is how God cornered me. So immediately I went to find my wife Margaret, who was in the kitchen, and told her things that I had never told her in my life before.

Margaret Nowell:

And when he came in I realised that something was about to be said. And he told me how he had been disloyal to me with his attachments to various women, and at that point I laughed, and he said, ‘What are you laughing at?’ I said, ‘It struck me as being funny and I am so relieved. I was afraid you were going to tell me you didn’t love me any more and wanted a separation.’ And immediately there came a new trust and love between us which developed as time went on.

We never quarrelled. At that point we realised that a frail bridge of politeness between us which bridged the chasm of misunderstanding and from then it was as if our marriage had been started all over again. I used to think that his job was in the tannery. I had plenty of things to do. I had the home. I was a Magistrate. I was a governor of schools. And my time was fully taken up. But one day my husband began to tell me of his problems at work, and that he feared a strike. So we said, ‘Why don’t we listen to what God has to say to us?’ and the thought that came to me was, ‘Why don’t you be as honest with the men as you have been with me? It works at home, why shouldn’t it work in the tannery?’

John Nowell:

Well I was furious, but deep down in my heart I knew that my wife was right. But it was some time before I could bring myself to do it. And then certain circumstances arose which I knew meant I had to do it. So I called all the men in the department, including their foremen, and told them that I had come to a decision that the right way to conduct things was on a basis of absolute standards of honesty and unselfishness, that I wanted to find what was right and not who was right. And I wanted them to help me in carrying out this idea.

Well the result was electric. One man said straightaway that he had never believed that he would live to hear a boss talk like that, and later on he told me that he lived for three points of time: the finish at 5.30, when the buzzer blew, Friday night when he got his wages, and Saturday noon when he went home and got changed for the football match. And then he said, ‘You believe me the other day the buzzer blew and I suddenly realised it was blowing and I was working. I hadn’t even looked at the clock.’ And there was another man said, ‘Perhaps this is the reason for the new responsibility shown in our work - that we used to think when we came to work it was 8 hours hard labour. Now we feel it is home from home and we are free to speak our mind.’ Another man rather took me aback because he said to me, ‘I find you are human. I thought you lived in a different realm altogether from us.’

Well the new atmosphere created in this department was such that we were able to make a wage arrangement to the benefit of all concerned. The men were paid on the tonnage that was sent out, which varied according to the orders we received. And it meant that they were never quite sure what they were going to take home. So we came to an arrangement whereby we took an average wage based on the piecework and they would be paid that every week regardless of what was sent out, and the understanding would be that if there was a pressure of work they would work overtime, but if there wasn’t any work that particular time they would not lose anything. And from then on there was never any basic trouble in that department, whatever may have arisen in the work - and trouble did arise in the rest of the works.

About 2 years after the start of the Second World War my colleague, who was on the production end, died and the Directors asked me to take over the whole control of both production and sales. Then there occurred an event which came as a complete surprise to us all - the works came to a stop for a day. It seemed to be the accumulation of grievances that went back for along time. It was then that I decided I would have a straight talk with the chief shop steward. I went to him and I said, ‘Tom, I have not trusted you and I have never given you any reason to trust me, and I am sorry about that. What I want to do now is to operate always on a basis of complete honesty, with all cards on the table, and try and find out what is right rather than fighting over who is right.’ His reply was, ‘Well that sounds all right. But will it work?’

Then I had what was to us a revolutionary thought. And that was to call in the trade union and to ask them to go over the whole of our wage rates. These were based on piece work, and depended on the amount of work done by the men, and had been built up over the years in a rather haphazard way, on a basis of bargaining without any real reference to the merits of the case. So I called in the trade union. We had been an anti-union yard, which certainly was a shock to the men and a shock to the Directors. But we went through the whole of the wage rates on the basis of skill, conditions, and arranged a framework which gave extra earnings to some men while to others it relieved them of what was excessive work even though it meant slightly less earnings. But this was agreed by everyone and remained a framework that never varied, and meant that for the whole of the period of which I was in charge, we never lost a pound of production nor an hour’s work.

Margaret Nowell:

I am now 92, and we are shortly celebrating our Diamond Wedding Anniversary. And in one of my wakeful moments in the night thinking back to the old days, and that talk with my husband, an unexpected voice said to me in clear tones, ‘You were a jealous, demanding and possessive wife’, which made me a silent one also. I thought, no wonder John looked for the company of other women.

John:

A large sole leather tannery on Merseyside, open pits, nine feet deep of acid tan liquor. Green greasy hides that smelled to high heaven. Not a savoury environment in which to work, and before automation hard slogging work, hauling heavy hides over and into the pits. You need a sure sense of tread and a poor sense of smell to work in a tannery. Every year the tanning company turned 200,000 cattle hides into £7 million of sole leather, employing some 500 workers. The leather was very highly regarded and the company increased its output tenfold. But there was an even more important product than leather that came from this tannery - one day a lorry load of hides arrived from the port of Liverpool. The driver had never been to this works before and the hide store seemed packed full. The men who discharge hides came up, looked over the load and the chargehand said ‘We can get so many over there, and I think so many into that corner, and the rest of them should get there, so let’s get to it lads.’ And in no time the load was stowed away, and the driver exclaimed, ‘Ill be damned! These fellers work like a team. At other places they take as long to decide where to stow the bloody hides as these do to unload them.’ He had spotted this other product.

Jack was a member of the recently-formed works council. He was a rough diamond and always sported a red handkerchief knotted around his neck. He was a veteran of World War One and a trade unionist for 40 years. In the Depression that followed the war years he was forced to sing in the streets to eke out the pittance he received on the dole in those days. In giving his convictions about the works council, Jack said, ‘I learned teamwork in the army in those war years, but couldn’t find it in the days of peace. Here I have found it again. The works council and what it stands for is the biggest thing that has happened in the annals of the firm. We will fight for it with all we have got, so that the same ideas can go to the whole of industry and out into the world.’

The works council became the focal point of this teamwork. It was long before works councils were recognised as an integral part of the industrial setup. And it was not formed to create teamwork but as a means of implementing the new spirit which was developing in the works. Its constitution was drawn up in cooperation with the trade union. It consisted of an equal membership of workers, freely nominated and elected by ballot to represent each department and of management, appointed by the General Manager, who was ex officio chairman. Later by common consent a joint chairman for the workers was also agreed on, appointed by them. The first Minute of the first meeting of the works council reads, ‘This can be a memorable day in the history of the firm because it marks where we cease to regard management and labour as two conflicting parties and think of them as people with a common interest to serve. Here we can together work out a new basis of labour-management relations and in doing so we can be building national unity. All should feel they can speak freely, without fear or favour, with every opinion honestly expressed and every decision based on what is right and fair.’

Leslie Wells was the trade union official, who helped in the formation of the council. He was invited to attend one of the meetings later on and he said, ‘I have had 20 years experience of works councils and attended many. But I have always had a fault to find, though I could never express what was wrong with any particular council. It was when I came here that it suddenly struck me that what had been missing from all the councils on which I had sat or helped to form, what was missing was definitely the team spirit. The spirit that has been embodied in this council has through the trade union been broadcast to many works in a reasonable radius of this works; on many occasions I have given this tannery as an example.’

One of the members was asked by a visitor whether these ideas were accepted by the workers as a whole. His reply was, ‘The great majority accept them. There are a few who don’t like them, but they are not happy and they are bypassed.’ And it seemed that a few of these sceptics had nicknamed the council the ‘nodders council’ because of the unanimity of the decisions that were made. In fact one department decided to elect a representative specifically to break up this unanimity. After he had attended two or three of the meetings the men got at him and said, ‘You aren’t doing your stuff. They are still turning out these unanimous decisions.’ ‘Well what can you do?’ came the reply. ‘The decisions are right.’

What was the secret of this teamwork? In 1941 the Managing Director died and the Chairman of our company, who was also head of an associate tannery, took over temporarily. There was widespread uncertainty and lack of confidence. This focussed in a trivial matter in one department and there was an unexpected unofficial stoppage, which brought the works to a standstill. This lasted only for one day but revealed a resentment and bitterness of which we in management were unaware. Shortly after this the Directors asked me to become General Manager of the whole works as well as of sales, of which I was already Director.

What could I do about the situation? Now I had always considered myself to be a Christian. But one day I was asked if I applied the absolute standards of the Sermon on the Mount in business - things like honesty, purity, unselfishness and love. I said that was impossible in business as it was today. The answer I got was, ‘Yes, impossible for you, but if you have the courage to ask God he will tell you how you can.’ This was a challenge and I decided to try it. The thought that became increasingly insistent was that the loss of confidence and the resentment in the workers lay largely at the door of management and it was up to me to take the first step.

I knew this meant an honest talk with Tom Tattersall, the chief shop steward. A man whom we in management neither trusted nor even recognised. This I shrank from, but I knew that the time had now come to follow this thought. Now or never. So I did. I said to Tom, ‘We have never given you any reason to trust us and we have not trusted you, and I am sorry about this. I want to begin now on a different basis altogether, of complete honesty with all the cards on the table. Can we fight together for what is right, instead of wasting our time on finding who is right?’ Well, Tom’s reaction was ‘That sounds a fine idea, but will it work?’

The next thought that I had was equally startling, it was to invite the trade union to come in .................... (this next piece I am not typing out, but is a repeat of what has already been said earlier in the tape as is the earlier part of this section)

...

The news of what was happening at the tannery began to spread and HM Inspector of Factories in London had heard about it and asked the local inspector to call at the tannery and to give him a report of what he found there. So when he arrived I asked the shop steward if he would take him round the place. I don’t know whom he saw or what they said to him. But when he came back to my office I asked him if he would tell me what he considered was happening here. ‘Well, you’ve certainly won the confidence of the men and you seem to have set up something that is Christian. What you are doing here is going to affect the community.’

Then the works council were invited to go to the industrial session of a World Assembly of MRA at Caux in Switzerland. There they told their story, and the result of this was that we began to get visitors from all over the world. I would like to tell you about two in particular. One was a man who had been assistant commissar of forestry in Russia. He had escaped to Austria and then came to Britain. He visited the works. I was away at the time, so I have no idea what was said to him by the members of the council. But his interpreter told me that at one point he said, ‘I see here my boyhood’s dream. This could never happen in a communist country. These men are free. I can see it in their faces.’

Another visitor that came was Mr Nanda, who was the Minister of Labour in the province of Bombay in India. And later a member of Mr Nehru’s government. Again I was not present when he spoke to the works council, but his comment afterwards was, ‘This is the answer that India needs.’

You may be asking ‘What was the attitude of the rest of management to these ideas?’ Well, take the case of Mr T, who was head of the main production unit. Jack, as he was usually called, said, ‘I used to think the best foreman was the best shouter, the chap who could drive the hardest, so I watched with great interest how these new ideas of teamwork made out. Finally I went to a conference where this new approach to industrial relations was being considered. In a time of quiet at one of the sessions the thought came clearly to me how wrong my attitude was and that my first move must be to talk to the man in my department whom I hated. He was truculent and a trouble-maker. He was the bane of my life. So I went to him and said “Ted, I want to say that I am sorry for my attitude. I have hated your guts, but I want to try a different tack. I want to see if we can’t cooperate and work together.” I think Ted’s jaw must have dropped. He looked at him and said, ‘Tha cans’t do it. I’ll give thee a month.’ At the end of a month he said, ‘I wouldn’t have believed it. It must be summat pretty big if it’ll shift thee.’ But the fact is that that man became the most cooperative worker in his department.

This chief production manager, Jack, was asked what his feelings were about the works council. He said, ‘We on the management side don’t just get our way. Sometimes we get a drubbing because we have not done the thing that is right and we ought to have that drubbing. We mustn’t resent it. We must encourage it. This council has reached out much further than ever we thought and carried management along much further than we ever dreamed we were going. But if you are out to get the thing that is right by everybody, you can’t hold things back.’

The proof of that last statement is to be found in the results which can be expressed both in changed attitudes and statistics. Expressed statistically, perhaps the most outstanding fact is that the productivity per man at this tannery was 25-30% higher than the average for the rest of the tanning industry. Another noticeable and unexpected feature was the improvement in the health of the employees, as measured by the time lost through sickness and parallel with this was a dramatic drop in the accident rate. Absenteeism - that is absence without permission, except of course for sickness - steadily decreased to 0.01% for the men and 1% for the women. Labour turnover was almost nil, and late starting ceased to be a problem. We worked out that the average time lost per man was 2 minutes per week, and in the case of women and lads only 10-15 per week. The rules about lateness and also the times and duration of teabreaks were all agreed by the works council. And they carried more weight than all the edicts of the directors. Except in the case of lateness, none of these results were planned. They just happened. We cannot gauge the penetrating power of a God-inspired idea. As one of the older employees said to me, ‘We have much to thank you for and I don’t mean improved conditions. I mean that ideas were in circulation in this works that many of us knew were wrong but we had no answer. You have given us the answer.’

But more important than the statistics was the change in attitudes - the attitude to work changed. One of the packers in the warehouse told a visitor, ‘I live for three points of time .............. (am not typing this passage out as it already appears earlier in the tape)..............

Then there came a new responsibility. Every piece of leather passes through the hands of some person as it progresses from department to department. The supervisor of course is responsible for the condition of the leather as it arrives in his department but he cannot see some of the defects, which only the worker who handles it does detect. We found that the men began to report any such faults, which had never happened before. But as one man said, when management began to take an interest in us, we took an interest in the leather. The quality of our product naturally improved and we received many congratulatory letters from government contractors. There was a well-known Leicester manufacturer of women’s footwear who, when our representative called one day, invited him in to the board room in order that they might express their appreciation of the service we had given in the very difficult post-war years, both in quality and reliability of delivery, which they said they did not get from other people.

I was to discover that men changed radically without my knowledge.

There was a man, Frank, who was known as ‘the bolshie’ - a very bitter man. And he had some cause. When he started work he was under the impression he was going to be given a job in the office. He was given a broom and told to go and sweep up in the drying sheds. The next grievance he had was that when he became 21 he was told that there was no man’s job available, if he cared to continue on youth wages he could do. But then he got married and his wife contracted TB. She became seriously ill and the doctor advised Frank to take her away as soon as possible. He asked permission from the manager but was told, not unnaturally, that he could only take his holidays when the works closed, which was some time later. Possibly the management should have investigated more closely what the circumstances were, but there it was. Shortly after this she died, and he became a totally embittered man, and his one aim was to give the utmost trouble to management.

He was one of the gang who did the discharging of coal for the boilers from the canal boats onto the storage dump. It was a dirty job, with shovel and barrow, and when the men finished they were as black at the coal. We put in an automatic unloader which quickened the time and relieved the work. But of course it meant an adjustment of wages, and the men didn’t think it was fair. So I asked them to come and talk it over. Before the chargehand and the gang could say a word, Frank tore into me, told me exactly what he thought about management and me in particular, and why was it that always the workers had to take the risk if there was any alteration? Let the management take it for a change. I remember now that I said to him, ‘Frank I am not concerned whether I am right or not personally. What I want to know is what is right. Let’s get down and talk about it.’ Well in the conversation certain things transpired which resulted in a modification of our original plan. It was finally agreed and the work went smoothly forward.

Then Frank was appointed chairman of the shop stewards’ committee, which used to meet monthly to consider any grievances. This caused me some apprehension. Then six months later in the winter there was a power shortage, and it meant that we had to stagger the work to relieve the peak periods - this would mean inconvenience for many men in the hours they worked. We put forward our plan. Now Tom Tattersall, who was the chief shop steward, was ill and therefore it fell to Frank to be his deputy. After I had explained the plan to the men concerned, I asked Frank if he would say a word as well - very apprehensive as to what might come. But to my surprise he spoke very soundly, and fully endorsed the scheme, which went through. I said to him afterwards, ‘I was grateful for what you said, not because it was my scheme or what we had put forward from management but because I felt that you really were concerned to do the right thing.’ ‘Oh yes, I have changed,’ he said. ‘Oh, how’s this then?’ ‘Well you remember what you said to me in that room about finding what’s right as the important thing? Well I watched you to see whether you did it and you seemed to me to be sincere. Unfortunately, the more I looked at you the more I looked at myself, and I saw that I wasn’t right! So I just had to change my ideas.’

So then I took him to see an MRA industrial play, which dramatised this idea of cooperation in industry on the basis of what is right. And he said to me afterwards, ‘For the first time in my life I have met men in industry who are giving everything without asking anything in return. That is what industry must find.’

Another discovery I was to make was that God was the best businessman. Most people have forgotten the strike that happened just after the war, when all the dockers in the country ceased work. This created a very grave situation for the tanning industry - so many hides had been sunk by submarine that the supplies were minimal, some tanneries having only a few days’ stock. Most of the tanners at once put their men on short time. Some of them even said, ‘This will teach them the folly of an unofficial strike’ (which this was). I couldn’t see it like that.

So I sought the mind of God as to whether he might have something to say and a certain plan came clearly to me. It was to plan production for one month, which meant - as we had only a fortnight’s supply of hides - going on to half time. To guarantee every man in the plant his average wages, whatever work he was doing. To take the men who were redundant to production and put them on maintenance work, which had been greatly neglected during the war. This could be a costly business because production wages were vastly greater than those we paid to men doing maintenance. So we worked out with the supervisors of the various departments a programme of work which we might call ‘spring cleaning’. We told the trade union about this and they were very pleased indeed with the idea, quite naturally. Then I told the works council, and was rather interested to hear one man say, ‘It is a very good scheme, but I know these men and if their wages are guaranteed you cannot expect them to work very hard.’ I said, ‘I’ll take that risk.’ So we called the men together and I explained the plan and the trade union official himself urged the men to justify the trust which management had put in them.

About 3 days after the scheme had started, the head of the main department came to me and said, ‘I have never seen men work like this. They will have finished this cleaning programme long before the month is up.’ And so it was. At the end of three weeks we had to find another week’s work. At the end of the month the strike stopped. The docks opened and the hides which we had lying on the docks came in and we went onto full production. The comment of the staff was, ‘This has been a brilliant idea. Now instead of the men being disgruntled because of lost wages they are on their toes and into it with full production.’ And the men themselves, I was told, said, ‘When we had no plan for ourselves the management had a plan for us.’

I have said that this revolutionary change in the tannery began when I was honest with a shop steward, but it is necessary to go much further back for the origin of my own change. I was active in church work and many other good causes and considered myself a good Christian. Then I met the ideas of MRA, with the insistence on the absolutes in moral standards and the need to give time to God to get his direction. The absolutes I ruled out as too idealistic for this world, but the listening for the voice of God I knew was an essential factor of spiritual leadership, though I had never acted on it. I decided to take time in the early morning. The clear thought that did come to me was that if I would be effective I must start by being honest with my wife and my family. This I could not bring myself to do.

Then a young man came to see me. He was a research chemist and a youth leader in a local church. He said he was in a mess. He had lost his faith and his affection for his wife and family and he just didn’t know what to do. Could I help him? We talked over things for a little and then I said, ‘Well I am not the one to tell you, but I am learning that if you mean business and listen to God he will tell you what to do very clearly.’ We were quiet together. What came to him I don’t remember, but I know what came to me. ‘You will never help this man or anyone else until you have been honest with your wife and your family.’ So when he had left I immediately went to find my wife, who was in the kitchen.

Margaret: I was ironing. I knew something was going to happen and my heart stood still. I was afraid he was going to tell me he didn't care for me any more and he was going to leave me. He then told me things he had never told me before, and his attachments to certain women. And I laughed with relief. At that moment I realised that it was a frail bridge of politeness between us, but our marriage was remade and a new confidence was born. My husband began to talk over some of his problems, and on one occasion I suggested we should listen to God and the thought that came to me was, ‘Why not be as honest with the men as you have been with me? It works at home, why shouldn’t it work in the tannery?’

John:

I was furious. I almost began to wish we hadn’t begun to talk over our problems together. In fact I flatly refused to do it. Then the circumstances of the stoppage transpired, and I knew that I must act on the thought which had come to my wife. It was then that the miracle at the tannery began.

I am now 87 years of age, and there are certain indelible lessons I have learned over the years of my industrial experience which covered the pre- and post-war years of World War Two. Things were very different then, conditions were different, attitudes were different, the industrial climate was different. But two things remain unchanged - human nature and God’s truth. I found - as have countless others - that when a man accepts God’s truth as a way of life for himself and applies it as a directing force in all his affairs and operations - a power operates outside himself, which brings change in men and situations. When I as a boss renounced deliberately my power to control in order to find with others concerned what is right, then this power of change operates, and problems which seemed incapable of solution are resolved. We are today using a new type of energy - nuclear energy, which is not generated but released. What can release the unknown energy potential in men? The story of the tannery shows what can happen when men are set free, free from their fears and hates and greed. The priority production of industry must be free men, as I have said, men free from fear, free from their hates and greed, free under God to remake the world.

English