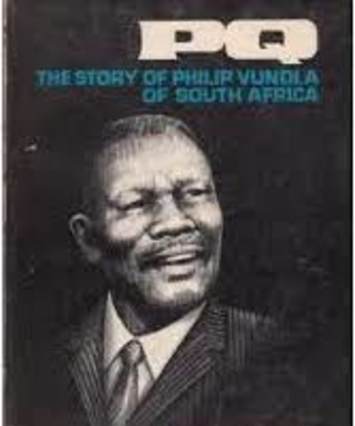

Philip Qipu Vundla was born in 1904 to poor peasant parents in the Ciskei area of South Africa. Maize was the family's staple diet, but they often went to bed without a meal. His sense of injustice was awakened while he attended a mission school. Some white boys, who were below Philip in class, got the chance of further education. He did not, and became bitter and frustrated. In 1939 he was elected to the Advisory Board of the Johannesburg City Council and – remained there for 30 years.

Vundla worked in the gold mines and began to gather facts about the working conditions of the miners. When a Commission of Enquiry was set up in 1943, he gave evidence, The next week he was shifted to a dead-end job in the mine. Philip left to become a full-time organiser of the African Mineworkers Union. But there was no salary. He had married Kathleen, the daughter of an African royal family. Now she had to take in washing to provide for the family.

ln 1944, PQ organised one of the first black demonstrations on behalf of teachers. The rally and march shook Jo’burg and Ied to a salary increase. After a miners' strike in '46, the Government put a ban on meetings of over 20 on mining Iand. PQ left the union to pursue the battle elsewhere. ln '48 he led a boycott against a rise in tram fares. The 'blacks only' trams ran empty for two months. Philip was arrested and roughed up, The police described him as ‘one of the most dangerous men in South Africa’.

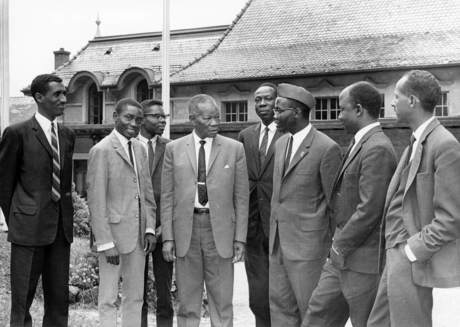

ln ‘52 he was on the Executive of the African National Congress, under the chairmanship of Chief Luthuli. The ANC had then no political affiliation. lts civil disobedience campaigns were always constitutional. Hundreds were jailed for defying discriminatory laws. But in 1960 the Government banned all African political organisations. PQ began to feel that violence might be the only alternative. But just at this point he discovered the secret of a new brand of leadership.

One day at the height of the crisis, a young white civil servant called at the Vundla home. He said he worked in the native Affairs Department. PQ was angry at having to waste time on such small fry, but was impressed by the man’s courtesy and humility – in contrast to the police who regularly raided his home. He was more surprised when the young Afrikaner said, ‘I have decided to give up my old ways of thinking and start living differently so that a man like you can begin to trust me.’ Their friendship was to have some remarkable consequences.

One night PQ was attacked and stabbed by a group of 30 young men from a branch of the ANC Youth League, which he had founded. His supporters called for revenge. But when he got out of hospital, Philip called a big public meeting to explain his ideas. 'Revenge is not the way’ he said.

For the next nine years his leadership was fearless, free from bitterness and international in scope, It had certain important features:

1) PQ believed that the liberation of the blacks in South Afrlca could be achieved by non-violent means, provided his care for people was as passionate as his hate had been. For him violence would have been the easy way out. And, he warned, ‘What you achieve by through violence, you will need even greater violence to maintain it.’ He knew all about boycotts from both ends. He often asked who would heal the bitterness after the boycott was over

2) He found a new way of dealing with those who opposed him. ‘My previous weakness was that I could not tolerate opposition,’ he admitted later in life. ‘It did not matter whether the others were right or wrong. Like all dictators I surrounded myself with organised protection.’ He was totally opposed to apartheid, but he neither feared nor hated the hard men he often met in Government offices. I will never be able to change them if hate them,’ be said. ‘They are fellow human beings. l can see myself in them and the things they do.’ By his genuine care and disarming honesty PQ was able to tackle peoples’ deepest attitudes without alienating them.

3) Vundla’s leadership became Increasingly effective as his principles and his practice came together. ‘You can't flght a war with one hand and create peace with the other,’ he said. ‘I was fighting for my people but neglecting my family,’ and he described how his children used to run out at the back door when he came In at the front. His home, whlch had come a poor third after politics and cricket, was to become his source of strength and unconquerable faith,

4) After an 11-month battle to obtain passports, PQ and Kathleen tried to help the outside world understand the true issues in South Africa. In Europe, Africa and America, Philip spoke fearlessly, with humour and passion. ‘We are fighting the wrong battle in South Africa—the battle of colour. I am convinced that it is too small an issue.’ ‘There are forces working to exploit colour, to divide people for their own ends. It is not a question of colour but of character.’ ‘Some people feel that the problems of South Africa can be solved by changing the laws. Let us by all means change the laws. They are unbearable, But in some countries laws have been changed yet the violence has grown, because men’s motives have remained the same. It is Important to change people as well as laws. Remember that those who say bloodshed is the answer have other people’s blood In mind, not their own.’

When Philip Vundla died in 1969, a two-mile cortege of cars and buses carried men and women of many races who came to honour this practical revolutionary of the heart.

English