Few actors know that their acting has saved lives. Michel Orphelin is one. His most vivid memory of a life on the stage is of a young man coming to him after a show and telling him that he had given up his plan to kill someone. This was in north-east India, where a guerrilla war was raging. The man would have killed the general whom he blamed for the death of his cousin, Orphelin says, 'but would have lost his life in turn.' Thus two lives were saved through a simple sketch dramatizing a French woman's hatred of the Germans, and her decision to forgive for the sake of the future.

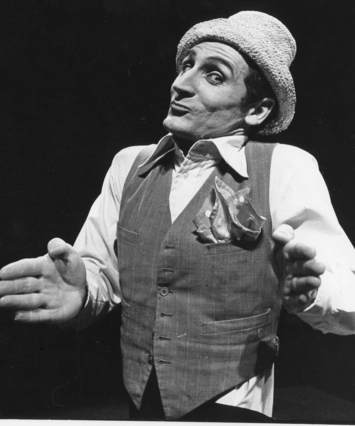

Michel Orphelin is a mime artist, singer, cabaret performer and actor; his hair and neatly trimmed beard are well-flecked with a distinguished grey. He has appeared on stage with Jacques Brel and some of the greats of entertainment, but he has also learnt something about what his son Francois, a theatre student, calls 'the theatre of poverty'. The true avant-garde, Orphelin believes, lies in great simplicity. 'What is often missing in the complicated productions is that they no longer know how to speak to the heart.' Theatre, he feels, is about creating and transmitting a relationship of love. It should deal with reality; be simple, without being simplistic.

For the last ten years, Orphelin has been applying this theory in a one-man show. In Poor Man, Rich Man, he brings St Francis of Assisi into the electronic age and the consumer society. Having already presented the show in 12 countries, he will take it to London in May, and Poland in June. Like the saint he portrays, Orphelin reveals a trenchant turn of phrase and an unexpected modesty. 'I'm just a worker,' he says. 'I do what I can. We all want to plant flowers. We can't all be great gardeners, but we can spread manure and prepare the ground for the flowers to grow.'

His first memory of the theatre is acting the part of a seven-year-old, fair-haired princess. His father, a commercial traveller, never took him to the theatre. But through the scout movement and different youth groups he discovered that he loved making people laugh. He quotes with approval Francois Perrier, a giant of the French stage: 'I'd like to savour the memory of people laughing. It is the most comforting sound I know, a moment of magic. It marks the only moments today that allow us to recapture innocence.'

He did not believe in his talent, so he never dared to admit to himself or his parents that he wanted to become an artiste. They had sacrificed so that his brother and he could study, and he did not want to let them down. So Orphelin went to a hotel school. There he and two friends formed an act, Les trois Horaces, and eventually launched out as professionals. For 12 years they toured together, appearing on television over 70 times.

At first, he revelled in success. An early critic of their act wrote, 'They are artists, and they know it.' Orphelin admits, 'I was young. Of course I wanted to be seen, and to be the best, to be the star, loved by the public, and especially the ladies! But,' he goes on, 'you quickly realize that it isn't enough. You find that the essentials lie elsewhere.' Orphelin found teamwork difficult, and there was also an unsatisfied longing to answer the deeper needs of people. 'There's more to life than making money. There's the why of it all; does my life have any meaning?'

Sense of certainty

A turning point in his life came during a holiday in Brittany. He'd gone with a good friend, a woman who had a real and living faith. He thought that he had fallen in love. She told him that she had been a nun, and that although she had left her order, she intended to keep her vows for life. 'It's interesting, but not easy, to compete with God,' says Orphelin. As he sat one evening in emotional turmoil, watching the sun set in the sea, a sense of certainty flooded in. 'God exists. I've met him. He was there for me,' he says.

He came back to Paris having decided, 'If he exists, I must do something for him.' He started going to Mass every day before work. The priest, assuming him to be a seminarian, was amazed to learn that he was a variety artist working in cabaret. Orphelin had found in Christianity what he was looking for. He did not want to do just anything, to play any part simply in order to be a success. 'I wanted,' he recalls, 'to pass on what I'd found - a new sense of harmony of the self with self, with others, and with creation. I was ready to play the Devil if the aim was to bring new life to people.'

Yet he found that his new faith did not automatically resolve long-standing problems of relationships in his work, and with his mother whom he loved, but with whom he fought continually.

Then, coming home from the cabaret at two o'clock one morning, he found lying on top of the refrigerator a pamphlet about a movement called Moral Re-Armament. He was intrigued, and got in touch with 'people who applied their convictions to change themselves and to change the world'. Later, on a visit to the MRA conference centre in Caux, Switzerland, he saw a play which shook him: 'It was as if I saw the Cross on stage. It was a call to transmit a luminous Cross to people.' He rebuilt his relationship with his mother, who found a faith in turn. He returned some poetry books that he had 'borrowed' from a friend four or five years before, enclosing with his letter of apology a spiritual book as restitution. He heard nothing back. But a year later, by chance, he met the person involved. 'I was in a black hole when I got your letter and book,' this friend said. 'They changed my life.' This experience, Orphelin says, taught him that when you obey the little thoughts that God gives, he can use you to help others. 'If the apostles testify to the risen Christ, that is one thing,' he says, 'but we also need experiences that we have been instruments in the hands of the living God. If he exists, then everything becomes possible. If you find an experience of change for yourself, if you have been handicapped and then you are renewed, you say, "Why can't others experience this, too?"'

He gave up his dreams of success and glory; he wanted to serve God, even if that meant never again standing on a stage. This was not such a difficult decision as it may sound, he admits, for the world of entertainment can drain you, and he was rather sick of it. However, friends asked him to play in the musical revue that took him to India. He accepted, though it was not easy being away from his wife, a violinist, and his son and daughter. Yet through that revue he saw that 'in simple ways, you can give people the essentials'; so a desire was reborn in him 'to make theatre', as they say in French.

Just a pipe

'It has been as if God gave me back a hundredfold all that I'd given him,' says Orphelin, as he talks about the experience of putting on the play about St Francis. 'It is a high-level professional show that demands absolutely all of me.' He had never believed that he could hold the stage alone for two hours, and really grip people. 'This play has given me a lot. It has shown me my calling.'

Orphelin knows that he is not widely known and probably never will be. 'But I think I may have helped people,' he says. He has been very touched by the comments of his audience. 'But who am I to touch people like this?' he wonders. 'I'm just a pipe for the living water of the Creator to flow through to a thirsty public. All I can do is to try to be a clean pipe. It is essential to have pipes, but they are only pipes.' He was never foolish enough to have dreamt of being water himself, he notes.

Poor Man, Rich Man has been an ecumenical experience. Hugh Steadman Williams, the author, is an elder of the United Reformed Church. A Methodist wrote the music, and an Anglican directed it. The Protestant minister responsible for the hall where they were playing in Edinburgh was amazed to see Catholic monks 'in costume' at the premiere. Orphelin sees St Francis as a great bringer together of people, and believes that this play has helped Christians to be proud of their faith. Christian artists need to feed the Christians and be apostles of the great gifts of God to non-believers, he asserts.

Orphelin recalls a nun saying after a performance: 'You have helped me to rediscover my calling to poverty.' He also tells of a couple in Belgium who spoke to him at the end of a show. They had adopted three children and were thinking about adopting a fourth. What should they do? Some nights later, in another town several hundred miles away, there they were again at the end of the show. Could they have a word? They had taken the plunge, they said, but instead of one further child, they had been asked to adopt a brother and sister from Latin America. They wanted to call them Francis and Clare (after the founder of the women's order which grew in parallel with the Franciscans). Another couple told Orphelin that the play had helped them to avoid divorce and become reconciled.

The life of frequent travel and late nights has its lighter moments. He recalls his musical director ordering a piano from the nearest music shop in a small town. Testing the instrument produced some strange noises. When they opened it up, they found that some of the strings were broken. 'But are you absolutely sure you need to play those notes?' asked the delivery man. Orphelin once played for four months in a satirical revue in London called GB. Sir Harold Hobson, the doyen of the city's theatre critics, wrote in The Sunday Times: 'Most impressive of all - it is touching, funny and meticulously observed - is Michel Orphelin's mime of a fisherman... It brought tears to my eyes, which is more than the great Marcel Marceau ever did... His mime is un chef d'oeuvre (a masterpiece).'

But Orphelin concludes, 'We are all masterpieces. We only use a hundredth of what God gives us.' Here is an artist who seeks to awaken the artist in each of us.