In my 20's, at the urging of a good friend, I was encouraged to read every life of St Francis I could find. In the next years I read about twenty!

Here are some of the salient points I noted:

The first Franciscans had all the virtues, including the one which is nearly always wanting, willingness to remain unknown.

Francis was the incarnation of the Italian soul of the 13th century, as Dante was 100 years later.

Francis loved France. He owed France his name, his mother, and so much of the poetry, song and music that came into his life.

He wasted his life up to his 25th year.

No one before Francis, or since, has planned the future of an organisation with such sublime abandon.

Masseo, one of his followers, said to Francis: 'You are neither beautiful, learned, nor of noble family. Why does the world run after you?'

Francis: 'God looked down and could not find a smaller, more worthless person to confound the grandeur and learning of the world.'

Francis: 'Conscience is like a flea: when it comes to the weakest part of a person it bites. It's a wonderful thing that you can have a conscience without having the brains for it. You keep it, and it keeps you.'

Francis: 'I can't make you do anything, Juniper, that isn't in you to do.'

Brother Elias, his successor, loved Francis, but only thought he could organise his ideas better than he could himself. Was this not what Judas thought about Jesus? When Francis died the despotism and love of power came out in Elias. His ambition was never cured, and no one except those who gave in to him found favour.

Francis to a brother: 'With the Lord's help you have overcome your demand for power and privilege, but you need to do this not only once but 10, 20, 100 times.'

Father Eloi Leclerc, author of La Sagesse d'un Pauvre, paraphrases Francis's message in these words: 'God has not called me to found a religious order, a university, or a machine of war against heretics, but to live according to the Gospel, to live, simply live, just that but fully. People who live that way will create everywhere they go free communities of friends. They will be free because nothing will limit their horizon.'

And: 'To detach oneself from one's lifework is beyond human strength. You cannot create without enthusiasm. But in creating something man runs his greatest danger. His work becomes the centre of his world. It puts him in a state of radical unavailability. It takes a break-in of God to deal with it.'

And: 'The depth of a man lies in his power of reception.' (La profondeur d'un homme est dans sa puissance d'accueil.)

Cardinal Ugolini, later Pope Gregory IX, became Protector of the order. He was the soul of the group which compromised the Franciscan ideal. He succeeded in extracting from Francis a year's novitiate. And when he was Pope, he declared the Brothers were not bound by the observation of Francis' will. And the will was destroyed.

Everything that was done in the order after 1221 was either done without Francis' knowledge or against his will.

Francis had twelve followers in 1210, 300 in 1216, 3000 in 1221, and over 5000 at the last chapters. He felt swamped. Many did not know him personally or his ideas. He said: ` 'I am like a father rejected by his own children. They do not know me any more. They are embarrassed by me. My simplicity has made them ashamed.'

Bonaventura, when head of the order in 1260, was commissioned by the Chapter-General to write the official life of St Francis. He left out Francis' approach to learning, manual labour, lepers, poverty, and passed over in silence Francis' will. The Assembly-General, over which he presided, forbade the friars to read any other life in future, and even ordered the destruction of the legends that till then had appeared on Francis. The result is a vague and pious figure.

The real St Francis began to be rediscovered six centuries later through sources that had been carefully hidden. One of St Francis' contemporaries recalled him preaching as follows: I was studying at Bologna, I, Thomas of Spalato, archdeacon in the cathedral church of that city when, in the year 1220, I saw St Francis preaching on the Piazza before almost everyone in the city.

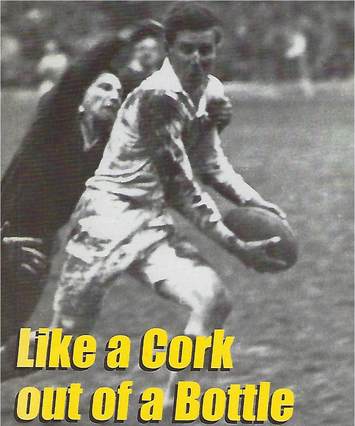

The theme of his discourse was the following: angels, men, demons. He spoke on all these subjects with so much wisdom and eloquence that many learned men who were there were filled with admiration at the words of so plain a man. Yet he had not the manner of a preacher, his ways were rather those of conversation: the substance of his discourse bore especially upon the abolition of enmities and the necessity of making peaceful alliances.

His apparel was poor, his person in no respect imposing and his face not at all handsome: but God gave such a great efficiency to his words that he brought back to peace and harmony many nobles whose savage fury had not even stopped short before the shedding of blood. So great a devotion was felt for him that men and women flocked after him, or he esteemed himself happy who succeeded in touching the hem of his garment.

English