'Putting People first' sounds easy enough to say – until you try it! But does it work? Over 25 years I was able to observe one man who not only proved that this idea was workable, but who believed that it is the only possible way ahead for industry.

Robert Carmichael was a tall, tough French employer. When he negotiated in the 1930's, his tight-lipped dominating style convinced the men opposite that the class war would have to be fought and won.

Soon after France was freed from Nazi occupation, a young officer of the liberating armies suggested to Carmichael that his attitudes might not help the rebuilding of Europe or even his own family. Later he met two Welsh mining couples who told him of their years of struggle and suffering at the receiving end of industrial decisions.

Robert's eyes were opening. He had two cherished industrial guidelines – 'What is profitable' and 'What is successful'. Did he dare add a third one – 'What is right?

Carmichael took a chance and invited a militant trade unionist from one of his factories to come with him to a conference.

To his surprise the man accepted. The factory had been running at a loss. Morale and production were low. There was often more action in the bar across the street.

Carmichael's accountant said the place had no future. At the the conference the two men talked. The worker decided to deal with the liquor problem that was breaking up his family. A new spirit began to stir on all sides. Productivity went up. Wages rose by almost 50 per cent and the factory began to rehouse many of the workers. Stage one had succeeded.

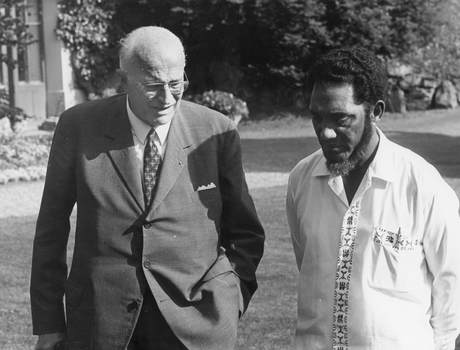

When Carmichael met his old antagonist of the '30s, Maurice Mercier, who was now General Secretary of the Force Ouvrière (Socialist) textile unions, it was a much bigger venture. Mercier had been at the heart of the Communist Resistance but was disillusioned: he knew that class war now meant atomic war. But was there an alternative? He was shattered when he heard Carmichael say publicly, ''We need a complete revolution in industry and this implies a fundamental change in our aims. It is no longer enough for us in management to work only for our profits, nor for the workers to aim only at earning their wages. We must combine our strengths to meet the needs of all men and to rebuild the world."

Mercier knew a revolutionary when he saw one. They kept in touch and learned from each other. Together they began to establish a stable and prosperous industrial partnership.

In 1951 Carmichael and Mercier signed a national textile agreement, the first in post-war France. 600,000 workers got substantial pay rises and were promised a share in higher productivity. Two years later there was a second agreement including pension schemes and unemployment benefits – 'in complete openness, in the common interests of the workers, firms and country'. I was working with Carmichael in Paris in the late '50s when inflation was rising dangerously. The Prime Minister appealed to the textile industry to give some lead. Management agreed to freeze prices. The unions accepted 8 per cent (most were demanding 20 per cent.) The Prime Minister said later in Le Figaro it was 'one of the first solid achievements on the road to the change which is essential for the economic survival of the country.'

But Carmichael's vision kept growing. 'What is right'– for the peasants in India and Pakistan who grow the jute for European industry? Robert went to see what conditions were like, although at times he was grey with pain from arthritis. He met the peasants in Bangladesh and visited their homes. One day as he limped through the streets of Calcutta, he suddenly thought, 'I am responsible for the millions of jute-growing peasants who are dying of hunger.' 'Nonsense!' snorted some of his European management colleagues and they began to oppose him. So he visited many on them in their own homes in Belgium and Germany, Britain and Italy. And although they felt that Carmichael's ideas were too risky, they were so won by his care and dedication that they started an Association of European Jute Importers, with Carmichael as President,

ln 1965, when Third World countries were pleading for stable prices for their raw materials, the jute employers were the first to meet in Rome and freely negotiate with the Asian producers – as equals. There were many difficult sessions. But they all knew Robert Carmichael, personally. His painful yet passionate fight had succeeded in establishing a genuine North–South bridgehead.

English