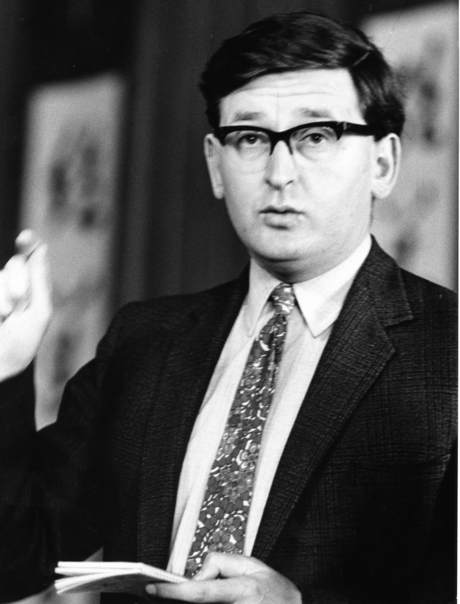

Address by Patrick Turner given at the memorial for Graham Turner, given in Salisbury Cathedral, UK, on June 25th 2024

We are here to celebrate the life of Graham Turner, husband, father, friend, writer, inspirer, encourager. What an extraordinary life. A life transformed to the end by a Damascus Road experience whose power never waned for him, or therefore for us. It was a joy and a privilege to have known him. He was the best of husbands, fathers and friends.

He was, above all, a true original, one of a kind. We are all made unique, of course, but he was especially so.

I am not going to attempt a potted history. But rather to pick out a few of the contours and colours on the canvas.

I will speak for just about 15 minutes, so those who want to sleep can set their watches.

Let me start by talking about words. He loved words and became a master craftsman, peerless on his best days. And not just words on the page. Words in endless hours of conversation. With his family and his friends, with the thousands of people he talked to. Words that came to him in the fastness of his heart when he sat to listen out for what God might have to say to him. Words which changed lives. Words which reached a very wide audience as he wrote on all manner of subjects in newspapers and books. Words which gave a voice to the countless people he interviewed. Words which were always telling a story. And then the peerless words of the King James Bible and the Prayerbook: words that still retained their music.

He became the interviewer and friend of politicians, industrialists, intellectuals, religious leaders, royals and even, we just learned, George Harrison on his 21st birthday. To give you a flavor of his politics, he was close to Mrs Thatcher and Boris Johnson. But he was never a pen for hire. His relationship with Mrs Thatcher ended when he refused, despite all the blandishments of Number 10, to expurgate some remarks she had given on the record.

To the end, he stayed true to his northern working class roots. In Heaven he will be able to look his father – the other person whom I have most admired in life – in the eye and say “I have held the faith”. Despite temptations along the way to follow other paths.

He retained the no nonsense straight to the point northern approach. He was never affected. He punctured pomposity. Although there is a rather good photograph of him, when he was working at the BBC as its first economics correspondent, elegantly besuited, with gleaming brilliantined hair and smoking a rather good-looking cigar. Everyone can have their off days.

He was the first person in his family to go to university. It was richly ironic that the northern working class lad should end up in the inner sanctum of the upper class, Christ Church in Oxford. He studied history and that helped him to start really honing his words. He had some demanding task masters such as Hugh Trevor-Roper, the historian who was arguably the best writer of history in his day, and who never knowingly under-appreciated his own abilities.

And then to the U.S. and Stanford, where he wrote his own thesis but also that of a friend who had not over-exerted himself. He wrote that one from scratch in the final week before it had to be handed in.

Then the Royal Air Force, where he was summoned for national service but turned that service into a short service commission because he wanted to be abroad. Abroad was Singapore. He became an education officer – God help those poor benighted souls.

He was the Captain of the Malayan cricket team, as he had been cricket captain at school in Macclesfield, and at Christ Church. He opened the batting and bowling, and led from the front. He claimed to aim to score 30 runs in the first 3 overs. It’s only taken 70 years for that approach to take on in England. For cricket aficionados, he scored a hundred for Christ Church against Radley and unwisely declared too soon. A Radleian called Ted Dexter scored a counter hundred and Radley won. The lesson: never feel sorry for schoolboys.

But then something extraordinary and unexpected happened. An RAF friend who had met a Christian group called Moral Re-Armament invited him to sit with him and listen to God, armed with pencil and paper. He also suggested that absolute moral standards – of honesty, purity, unselfishness and love, originally a kind of distillation of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount – were a good measure against which to test our lives. Our father, who wanted desperately to get out of the room but couldn’t think of a way to do so, protested that he didn’t believe in God. The friend said that didn’t affect God’s position in the slightest.

To his amazement, thoughts started to pour in, which he wrote down. Thoughts that he knew were not of his own own making. Practical and uncomfortable thoughts of wrongs to be righted.

But even more important, God Himself poured in. Our father described it as like a wave of love. Where there had been emptiness and unbelief, despite having attended church several times a day on a Sunday during his childhood, there suddenly came an unexpected certainty. And a never previously experienced joy and lightness of heart.

There also came the certainty that he had to follow the thoughts and put some things right. Including apologizing to the cricket team for being a dictator. No easy matter with bluff Australians and others in the team. He always said that obedience was key. No point in thinking the right thought if you don’t act on it.

He started a lifelong daily practice of listening. Silence came to be the beating heart of his life, but a silence that was humming with a voice. Towards the end of his life he wrote books on silence and on that voice. They summed up the heart of what he started to learn in Singapore and then spent the rest of his life learning.

And he spent the rest of his life wanting to give other people the gift he had been given. He was evangelical, not from any sense of obligation but out of love.

He was the kindest of friends and the best of listeners. But he was always willing to be direct and to say the things others feared to say, for love of his family and friends, and those he met.

For example, he told a fellow RAF officer in Singapore, who had a mistress but professed undying love for his wife in England, that he was a hypocrite. The officer was furious, but ended the affair. When he died some years later, his widow got in touch with our father and said that her husband had called him his best friend in Singapore. Our father was similarly direct with a number of others, including several British politicians.

Thus began a new road. A little further down that road, he was sitting in a cinema and heard a voice saying to him “I want you to be a journalist”. A voice so clear that he turned round to see who had spoken to him. Again, he followed the thought. And what a journalist he became.

Later, the voice prompted him to think of marriage to our mother, whom he had known from the age of two in their home town. He told God that he didn’t love her, so divine help would be needed. When he next saw her waiting for him at a railway station, he knew that he had fallen in love with her. He proposed there and then and was accepted. That wave of love now encompassed our mother.

This brings me to another central characteristic. To use an old fashioned word, he was uxurious. He was a man who liked to be married. He was pretty hopeless on his own. He waited a long time to get married but then it fitted him like a glove. He was immensely lucky in both his wives.

He was married to our mother for 52 years. They shared the closest of bonds. They really were soulmates, but not of the kind that only gaze at each other. They faced outwards and inwards together. She joined him in listening to God each day. They shared their failings and their fears. And they often spoke together at Moral Re-Armament conferences, each with their own inimitable style but also speaking as one.

They even survived working together every day when he started several decades of working at home in 1970. She was his constant companion, but also a tough literary critic and editor. She had been a formidable English teacher and had a very good ear and eye for words.

Despite prestigious billets on major national newspapers including the Daily and Sunday Telegraphs and the Daily Mail, a succession of books and sustained success as a writer, our father often struggled to believe in himself. Past plaudits did not persuade him that his next product would hit the mark. My mother helped to smooth out the highs and lows and to provide a rock solid home base. He repaid this care and devotion very fully during the long and rather debilitating illness that preceded her death in 2014.

His method as a writer was to take a subject and then talk to loads of people. On the phone. In person. Thousands and thousands of people. He had a knack for getting the best – and the most – out of people, sometimes to their detriment. He wanted to tell a story and make it sound like someone speaking to you. And that was literally the case. He gave countless people a voice. His writing spoke and it sang. But, when he was doing an interview on the phone and he repeatedly said “very interesting”, you knew he had stopped listening.

He rarely went to the office or schmoozed with colleagues. He liked home. He had given up drinking in Singapore, which made him a very unusual journalist. And popular with the people footing the bill for expenses at his newspaper.

He used a typewriter but never a computer. He couldn’t download, upload or email. When he had finished writing an article, he either dictated it down the phone or sent it by fax from the local post office. When more recently he said “I’ve sent you an email” that meant that his second wife Veronica had done so. Latterly he met people over Zoom, but couldn’t have worked out how to use it on his own.

He married Veronica in 2015; she was the widow of an Anglican clergyman who had been our local vicar just outside Oxford in the 1970s and 80s. They absolutely adored each other, and were very clearly made for each other. Veronica was and is an extraordinary and wonderful gift, as so many here can attest.

Veronica brought a fantastic family of her own, with children and grandchildren galore. They were an absolutely wonderful gift too.

Veronica gave our father a new lease of life. She also gave him an improved wardrobe. He had occasionally been capable of being smart, but tended to be sartorially challenged.

They moved from Oxford to Salisbury in 2016, to a marvelous house in the Cathedral Close with a view of this wonderful cathedral. They found here a set of fantastic and generous friends, and developed a very lively social life. The new lease of life also helped to keep our father writing – two more books, including an autobiographical one, appeared during those years.

Our father was a man of deep emotions and he often wore his heart upon his sleeve. You could see the emotional weather on his face. He voiced his thoughts and feelings where others would have held their peace. He was relentlessly and painfully open and honest. He had highs and lows and was not afraid to show it. This sometimes made him uncomfortable to be with, especially for those who prefer to avoid emotion or challenge. But that was what made him so appealing to so many. They could feel and see “one of us”, often in the raw.

He was a wonderful conversationalist with an amazing range. He saw a good conversation – whether a deux or with a larger group – as like a game of tennis. He always had so much to bring, both from his personal convictions and experiences and with his extraordinary range of connections in the wider world. He was also a great encourager – that has come through very strongly in lots of messages in the past days.

He was never dull and never too serious. He always had a mischievous twinkle in his eye. He had a puckish sense of humour – another way of playing with words. He loved jokes and practical jokes. And he knew that God’s saints are also the most light-hearted of people. That, combined with his kindness and sociability, his honesty and no nonsense approach, made for a life which was bristling with energy, with interest and with fun.

He was the most faithful of friends, building friendships which were often lifelong. Friends from his youth. Friends from MRA. Friends from church. Friends from Oxford and Salisbury. A friend serving a life sentence for murder. And he treated his family as friends, not just family. I counted him as my closest friend, alongside my wife.

Those friendships will be renewed in heaven in the years to come and his heart and voice will join the great chorus of voices in heaven. Each of them unique and each of them beloved in eternity by their Creator.

Thank you, God. Thank you, Daddy.