In 1945 a boy called Lagu was herding his father's sheep and goats at Nimule, near where the Nile flows into Sudan from Uganda. A man came running to tell him that the weekly steamer had arrived, with a message that 13-year-old Lagu had been given a place in a primary school hundreds of miles away. He must leave by lorry that morning.

Lagu was rushed to the local shop where he was provided with a shirt and a pair of shorts, but no shoes, and sent off on the four-day journey towards his first regular education. It was nine months before he came home for the holidays.

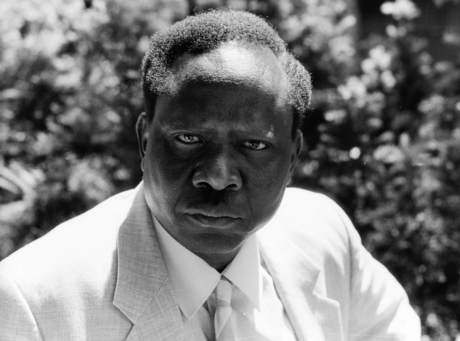

Over the next 40 years Lagu was to return to Nimule as a Christian, baptized 'Joseph', as a newly-commissioned officer in the Sudanese army, as a peacemaker after nine years as a guerrilla fighter, as Chairman of the new South Sudan regional government, and in 1982 as Vice-President of the Republic of Sudan. Now in temporary residence in Britain, he hopes one day to be back in Nimule as a farmer.

Sudan is the world's ninth largest country and Africa's largest, bordered by eight countries and the Red Sea. It took shape under the Ottoman Empire, was liberated in 1885 by El Mahdi, the Muslim reformer, in 1898 was conquered by an Anglo-Egyptian army. When Lagu was 24, it gained independence.

Today the country has been brought to the edge of disintegration by its second civil war since 1956, a product of the deep divisions between the Arab Muslim North and the African (and partly Christian) South. Central to the divide is the bitter memory of the Arab slave trade.

The first civil war ended in 1972, after 17 years. Now, once again, insurrection, siege, massacre, starvation and an exodus of dying survivors have turned South Sudan into what one British Minister calls a graveyard. For every one of the 250,000 Southern refugees in Ethiopian border camps, it is reckoned, one other has died of starvation at home or on the way. It is a holocaust in progress - but one which Lagu believes can still be halted.

Lagu knows enough about war - and something about peace. In 1963 he defected from the mainly Arab officer corps of Sudan's national army and joined the rebels in the South. For four years he welded them into an effective guerrilla force. For the next five years he was their political leader too. His tactics deserve study as much as those of Giap, Guevara and other successful guerrilla leaders of this century. Unlike them, Lagu says his motive was not Marxist or Maoist. 'I was a South Sudanese nationalist with some Christian reference points.'

Asked why he took up arms against his government, Lagu says he wanted to counter linguistic and religious aggression from the North. He also wanted to avenge a relative in the police who had been executed for mutiny. Why then did he decide to make peace? 'Because the cost of hatred and vengefulness was becoming too great for my people, and I saw in the enemy a willingness to compromise.'

The most famous episode in the peace process came in 1971, when a Sudan Airways civil plane, flying from the North, crashed in an area held by the rebels. A message was sent to Lagu at the rebel headquarters asking if the 29 surviving passengers should be killed or held hostage.

As he lay awake at night Lagu turned afresh to his Christian reference point. What would Christ have done with those civilian captives? And how could Lagu face Christ if they were killed? The next day the prisoners were escorted to the outpost of the nearest government-held town. 'They became our ambassadors in the North,' says Lagu. 'The government would not be believed if it ever again described us as savages.'

At the peace-signing in Addis Ababa in 1972 Lagu asked the Secretary of the African Council of Churches to recite his favourite prayer, which begins, 'Oh God, who art the author of peace'. Next day he flew into the national capital, Khartoum, to a hero's welcome. He spent six years integrating 6,000 of his fighters into the national army and was then elected Chairman of the newly autonomous Southern Region. In 1982 he became Vice-President of the whole country.

Thus Lagu has grounds to believe that his country's wounds can be healed. But he warns that it will be more difficult this time, because the struggle is now 'ideological'. One strong faction in the North wants to make the Islamic law, whose penal code includes amputation, the dominant law of the state. The rebel leadership, under the influence of Marxist Ethiopia, seems equally rigid.

Lagu respects Islam for a good reason. He is married to a Muslim. Amna was born in the South to an Arab father and a Southern mother. In 1955, when she was one, her father was killed with hundreds of other Arabs in a racial uprising by Southerners. The women and children were rescued by an Italian priest and then, as they fled towards Uganda, protected by the chief of Lagu's own tribe.

Lagu's first marriage broke down during the nine years he was fighting in the bush. When he returned to Juba, the capital of the South, he fell in love with Amna, a young teacher, and they married on Christmas Day 1972. Their four children are baptized Christians who also answer to Muslim names from their mother. As Vice-President's wife Amna was entertained by kings and presidents. Now she works as a 'dinner lady' in her youngest sons' primary school in London.

Lagu is clear that Islam's emphasis on the family helps his wife to be the person she is. He just wants to encourage Muslims to present their religion as a grace rather than a threat.

If he is critical of the way some of his Muslim compatriots behave, he is equally candid about Christians' shortcomings. The Roman Catholic Church in Sudan has maintained integrity, but the Episcopal Church to which Lagu belongs is still, at the time of writing, in schism between two rival Archbishops of different tribes. During a service at Khartoum's Anglican Cathedral last year a fight broke out between the two factions. A new bishop drew a gun and shot one of the congregation in the leg. As a result, the government had to close the Cathedral. There are numerous faithful pastors and lay folk, but Lagu laments the absence of a clear Christian lead.

Such guidance is needed amid the great sums of money which have flowed into Sudan for development and political parties over recent years. At one point Lagu was offered a million-dollar bribe from abroad and turned it down.

He found it less easy, however, to make the transition from autocratic general to democratic politician. He would sometimes rage against subordinates who failed to do his bidding. And he can show particular fury towards intellectual politicians who treat him as an unsophisticated soldier. 'I am still too slow to forgive. I don't reckon to start aggression, but I like to return it double.' The shake of the head indicates a man in conscious struggle against his own nature. With a rueful smile, he quotes one of his children: 'Daddy thinks he is still general of an army and we are his soldiers.'

At a Moral Re-Armament conference in 1987 he said, 'I have suffered from the complex of looking down on the young, just as I was looked down on by older politicians. Before, I thought it was only the older who could give wisdom and experience. Here I have realized that the old can also learn from the young.' He is no less combative for what he believes to be right. But there is an increased humanity.

The last four years in Europe have given him the chance to reflect on his turbulent past. When President Numeiri was ousted in 1985 there was no charge against Lagu, but he was immediately evicted from his government house. With civil war in his home area, and fearing victimization in the North, he sought residence for his family in Britain.

During his first year of self-exile he had to fight poverty, loneliness and despair. But old friends, Sudanese and British, sought him out for his counsel and helped as they could. Representatives of different factions pressed him for his allegiance. Though impatient, he came to feel he must be a peacemaker, available to all sides.

A case in point was that of John Garang, leader of the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), who invited Lagu to Addis Ababa soon after his arrival in London in 1985. Lagu recruited Garang into the guerrilla forces during the first civil war and later watched over his career in the national army, before Garang defected in 1983. Lagu thought long before accepting Garang's invitation, but eventually took it up in 1987. Once in Addis, he spoke with Garang like an older brother, agreeing there had been a valid cause for war but suggesting now was the time to settle. In full openness with both sides, he kept Prime Minister Sadiq El Mahdi informed of his journey.

For two months of 1987 - 8 this process was conducted from a hospital bed in London, where Lagu lay with a fractured neck vertebra after a road accident, receiving - at different times - the Sudanese Minister of State for Defence and the Deputy Commander of the SPLA. Later in the year he was invited to Khartoum. It was indicated that he could be given a ministerial post, but he turned this down, saying he wanted to be free to mediate. This enabled him to speak straight to Northern politicians about their failure to inspire trust in the South, and to Southern parliamentarians about the constructive role open to a democratic opposition.

A peace settlement, Lagu knows, would only be the first step towards the massive reconstruction needed in the country. The South is just one area of suffering. The ruined national economy is scarcely able to address the basic needs of the rest of the country. Development projects funded by other countries have been destroyed by the war.

It seems that the rest of the world is willing to help rehabilitate Sudan after hostilities have ceased. But Lagu feels some Sudanese politicians want power more than peace. This could lead to the permanent break-up of Sudan, not just into North and South, but a host of linguistic nationalities. There are indeed major grievances to be redressed. But, he says, 'Sudanese of all political opinions must forgive one another and agree to start a new political chapter.' He knows this is possible because of the warmth that has come into his own relationships with political opponents in recent years.

Lagu feels the aim must be a total reconciliation in all Africa's conflicts - Eritrea, Chad, Uganda, Somalia, to name a few. Any isolated agreement can always be undone by a neighbouring conflict. That is why he maintains his friendships with the leaders of other African countries, particularly those along the Nile.

Lagu has been a hard-living man, and it shows. He also has a strain of piety. He likes to quote the Irish chaplain of his school who told him, 34 years ago, 'When you are on your bed in the late night or early morning, that is the time when God may show you what you are to do. Don't tell too many people who might argue you out of it. Just go and do it.'

It was Lagu's attention to such inner prompting which saved the lives of the 29 plane crash survivors in 1971. Peace and reconstruction in 1989, he believes, depend on that kind of decision-making.