Some of the sixty Birmingham shop-stewards were beginning to yawn as the boss of a Runcorn tannery started speaking. The room was stuffy and it was a Sunday afternoon. But then his wife and children took up the story, then his chief shop-steward and the area union official - and they all came to the same conclusion. Everyone was now wide awake, because they had been presented with a complete case-history of 'revolutionary teamwork'.

That was 40 years ago. When some of the stewards tried out this idea in their factories it was to result in many years of effective and constructive leadership. In theory, teamwork in industry sounds very dull and tame. In practice, It can be the most radical and exciting adventure.

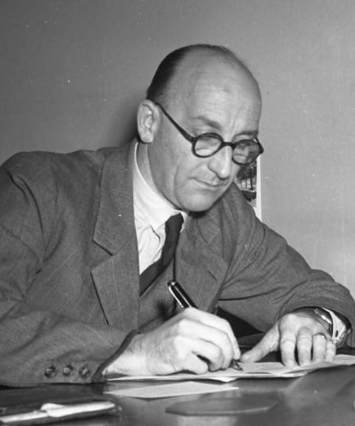

The tanner in question was John Nowell, born in British Honduras and brought up in Plymouth and Stockport. Nowell didn't plan to be a tanner; he had studied classics. But through some educational mix-up his plan for professional life fell through. He started work amid the greasy hides and smelly pits of the local tannery, for 10/- per week. After learning all the basic processes, ('You need a sure sense of tread and a poor sense of smell') he was transferred to sales, where by visiting shoes factories all over the country and asking what they wanted, he greatly increased the British sales of the supple 'American' leather which had become fashionable.

During World War II Nowell became Director and General Manager of the Camden Tannery in Runcorn, producing sole-leather. But there was war inside the tannery too. It was an anti-union shop. Nowell had a 'profound distrust' of the chief shop steward. He refused to negotiate. It took several months for the district union official to get a date. Wages were agreed individually. And everyone was afraid of the boss. In '43 there was a strike.

There was also deadlock in the Nowell home. 'A frail bridge of politeness' linked John and his wife Margaret. They and their three children lived in separate worlds. John's sister had given him a book entitled 'For Sinners Only'. He was not amused. After all he was a local preacher.

But when he read it he got the shock of his life. In the light of conventional Christian standards he had felt free to blame everyone else; the absolute demands of Jesus of Nazareth put the spotlight on him. His bluff was called. An honest apology to Margaret and the children began to restore family life.

But the problems at the tannery persisted. Finally Margaret said with that devastating wifely directness, 'John why don't you be as honest with the men as you were with me. It worked with me at home. Why not in the tannery?’ John was livid. But he knew the truth when he heard it.

He assembled the workforce and told them they would be working on a new basis. He called In the shop steward. 'Tom,' he said, 'I have not trusted you and have given you no reason to trust me. I'm sorry about that. I want to operate on a basis of complete honesty with all cards on the table on the basis of what’s right not who’s right.’

Tom was sceptical. But when John called in the union and asked them to go through the wage rates. He alarmed the directors, but convinced the workforce that he meant business. Finally a works council was created, long before they were fashionable, with an equal number of workers and staff elected in each department. This became the focus of the new partnership.

Things moved quickly. ln the piece-work operations, where weekly earnings varied widely, a guaranteed wage was agreed which gave a new sense of security. Absenteeism went down, and as morale rose, so did productivity, in some cases as much as 25%. Now workers could speak to the boss without fear or victimisation.

‘When management began to take an interest in us, we began to take an interest in the leather.’ A woman worker, in tears on retirement, explained, ‘I've been so bloody happy.’ 'From then on,' says Nowell, 'we never lost a pound of production or an hour of work and attained our maximum output.'

Camden Tannery gained a reputation. An ex-commissar from Eastern Europe said, 'Here I see my boyhood's dream fulfilled. These men are free. I can see it in their faces.'

It was with this solid background of domestic and industrial teamwork that Nowell took responsibility for the wider leather industry. He became President of the Association of Cut-sole Manufacturers, served on the Executive of the British Leather Federation and was for 21 years Chairman of the Leather Institute. They were years of crisis, as sole-leather was being replaced by synthetics. His colleagues acknowledge Nowell's courageous leadership.

The industry began to diversify into leather clothing. And of course, leather clothing, fashionable even with our ancestors, is definitely in again. l asked John Nowell, now in his middle-nineties, about his revolutionary concept. He replied, 'we hamper our progress because we persist in our preconceived ideas of socialism and capitalism and we are unwilling to let them go. We managers have assumed the right to have the last word as something inherent In the position. The moment I accept teamwork, which means a voluntary restriction on my personal rights of action and ownership, I have begun to create something far beyond socialism or capitalism. It is not the teamwork of those who agree, but of those who disagree. Who clash and change. The new dialectic if you like. I have to be willing to accept correction from my children, on the basis of what is right and also from the workers. When l as a boss I deliberately renounced my power to control, in order to find out with others concerned, what was right, then this power of change operated and problems which seemed incapable of solution were resolved.'

Perhaps this man has the 'cure' we are all looking for.

English