Sense of Direction

A slightly shortened version of an article by Rupert Cherry in 'Rugby World', April 1979

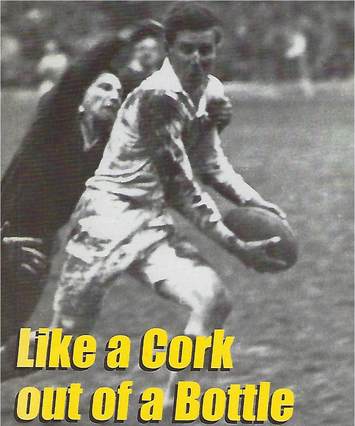

Brian Boobbyer played his all-too-short international rugby at the beginning of what I remember as one of the golden periods of English centre play. From 1950 to 1952, he won nine caps as an England centre, and I have no doubt that he would have had many more had he not chosen a way of life which took him away from the international arena. From a rugby point of view, and particularly from England's, it was a considerable loss.

England's back play was developing again after the interruption of the war. Men who were to become great centres, like Lew Cannell, Jeff Butterfield, and Phil Davies, were emerging in a build-up to a time when England would again win the International Championship. Boobbyer was among these players who promised excitement on the rugby field.

England won the championship in 1953. By then, Boobbyer had made a momentous decision. He was to devote his life to working for Moral Re-Armament, which seeks to dispel hatred between men and nations. He has done so ever since, and indeed, now he is fifty years of age, even more actively. There is no salary for this work, and as it takes all his time he cannot earn money. For 26 years, he has been able to devote his time and energy solely to influencing people's lives according to the beliefs of the movement, by speaking, preaching, by dramatic performances on stage, and by simply helping people in distress. It is made possible by the financial help of those who support the movement....

For a young man enjoying University life at Oxford, and a sport of which he is passionately fond, his decision, taken in 1952, was most remarkable. He was born in Ealing into a family thoroughly immersed in sport. Their most treasured possession is the ball with which Brian's grandfather, E D Shaw, later to become Archdeacon of Oxford and Bishop of Buckingham, made 78 not out for Oxford University against the Australians in 1882. That was against the bowling of the renowned Spofforth. Brian's father, who was a doctor, played cricket for St Mary's Hospital; his mother, also a doctor, although she did not practise, was a cricketer too, and her two sisters played lacrosse for England. Mrs Boobbyer [Brian's wife] is a member of the Rodd family, the best known of whom in the rugby world was Tremayne Rodd, now Lord Rennell, a great scrum-half for Scotland 20 years ago.

Brian himself was a Double Blue at Oxford for rugby and cricket. He played in three rugby Varsity Matches, and four Varsity cricket matches as an opening batsman. 'The kind who makes about 25 before lunch,' he says modestly.

In his first University match at Twickenham [in 1949] he played alongside Cannell and Oxford won a great match 3-0 before 60,000 people. Boobbyer says he learned a great deal from Cannell about centre play. In those days, the centre was expected to beat his opposite number by one of the subtleties of change of pace and swerve, and so make the opening for the wing. 'The first time I played against him,' said Boobbyer, 'he passed me three times in succession. Ever after that I watched him closely to see how he did it. The secret was leaning ever so slightly inwards as you came towards the defender to keep him guessing whether you would break inside or not. He had to check his stride, and then you accelerated rapidly, swerving well outside him. Cannell was fast, and so was I and I learned to copy him exactly.' It worked, for they immediately became England's centres.

Boobbyer played for Rosslyn Park and for Middlesex in a championship-winning year. He was a Barbarian, and in his three remaining years at Oxford was right at the top of the rugby tree. After the 1949 Varsity match, Oxford toured in France, and it was on this journey that he began to learn about Moral Re-Armament.

One of his best friends was Murray Hofmeyr, a South African who played fly half and later fullback for Oxford University and England. 'On that French tour', said Brian, 'we talked about things we had never spoken of before; about what we were going to do with our lives. Murray's brother was a pioneer of the Moral Re-Armament movement in South Africa, and I am a person of faith. I don't know what it was, but when your life is fairly easy and fairly successful, and you don't question things very much, there suddenly comes a moment when you mention these things that you have never mentioned, and you pose the question, how do you live your life, how do you relate it to the struggle in the world?

'I came back to Oxford and looked at my life to see whether it needed a change. I decided to make the experiment of taking time "in quiet" each morning to get a sense of direction. When I left Oxford, it seemed to me the most intelligent thing, and perhaps the most difficult thing, was to do for other people what someone had done for me, that is to find a faith and a sense of direction for life.'

So when Oxford went on tour to Japan in 1952, he went with them, and stayed there to try to dispel some of the hatred that remained from the war. For ten years he worked abroad, mostly in Asia, but for three years in America....

Boobbyer is a fluent speaker, and his chosen way of life is time-consuming so that he does not watch a great deal of rugby. Like most Blues, he goes to the Varsity match. He thinks the game is played much more efficiently now than it was in his day, but perhaps not always with the same flair - always excepting the Welsh. Whether players enjoy it as much now he could not say; probably they do. Neither was he able to judge whether there was more violence.

'People say it is more violent,' says Brian, 'but I can remember some very dirty games, including a Varsity match.'

In my opinion I think it is a pity we cannot go back to the days when Boobbyer was playing for England, the time when centres did such a lot more than just take the tackle and play for the overlap. When he was at Uppingham, he was not allowed to kick. Boys were taught to run with the ball and the result was one of the finest periods of back play in English history.

Reproduced by permission of 'Rugby World'

English