Steve Colwell writes to his children and grandchildren to try and explain what he and his brothers did and were part of, and where it took them.

Steve Colwell, August, 2020

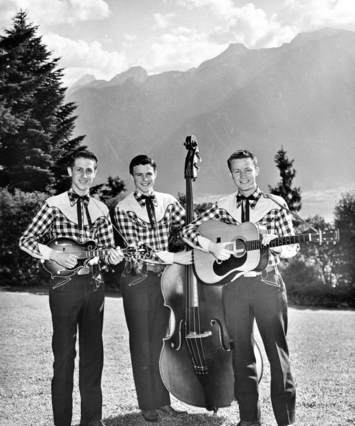

I think all of you know that my brothers and I were involved in music since we were “knee high to a grasshopper” as the old country saying goes. I was about 13, Paul 11, and Ralph 9. We decided to start a band one rainy day in the Los Angeles area where we lived. Bored with nothing to do during a spring break I went to the closet and dug out a guitar I had earned selling garden seeds door to door and we started learning a few songs from 78 speed records. Because western music and what was called hillbilly songs in those days usually had just three chords and a singable melody it was easy to learn and that’s the genre we gravitated to. Besides, for some reason, to the ears of three city boys cowboy songs rang true to us as did bluegrass style music which emanated from Kentucky and Tennessee.

So we put together a few songs. Our first official concert was at our parent’s cocktail party. We loved this new hobby so much that we continued learning new songs and performing where anyone would invite us as we mixed it in with school and sports. After a brief career recording for Columbia Records (it is said that we were in the youngest group ever to record on that label) and performing on the NBC Tex Williams weekly TV show for about two years, and other LA area concerts, we ran into a life-changing opportunity that radically altered the next twelve years of our lives. And following is what this is about.

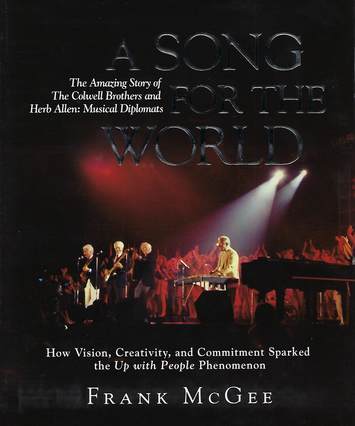

From 1953 to 1965 we worked full-time with an international program called Moral Re-Armament (MRA). During those formative years of our lives we wrote numerous letters from all over the world to our parents. Some of the information contained in the letters was used by Frank McGee to write the book about Herb Allen and ourselves called A Song For the World. These letters, several hundred of them, are housed at the University of Arizona library in a Colwell Brothers archive for safekeeping. They are available to you at any time to read and are indexed according to who wrote them and from which part of the world.

Many of the letters are long and hand written in cursive. Most of them tell of the ordinary people as well as the leaders in every field of life in some 60 countries whom we met or sang for. We also write about fun and interesting experiences traveling and seeing beautiful places. Then there’s everyday chatter with our parents and Ted about such mundane matters as our need for replacing worn out clothes and guitar picks, items hard to find in Burundi. By the way, as we received no pay we couldn’t have done this without the continual, generous financial and material support of our mom and dad.

These twelve years were formative, exciting, and challenging for Paul and Ralph, still in our teens and me, just one year out of teens when we began our journey.

What was this program called Moral Re-Armament to which we pledged our lives, and our parent’s fortune, and our sacred honor?

First of all, it was registered by the U.S. government as a 501(c)3 not for profit organization. Broadly speaking MRA’s mission was to change the world by changing individuals who developed into peacemakers and justice crusaders. Its targets were anywhere and any entity where there was division; for example, nations in Europe and East Asia ending the bitter scars of WWII, emerging countries fighting for their independence, helping to end apartheid in South Africa, labor management disputes, trying to bring warring tribes together in Congo, and even helping divided families. The organization flew under the radar of many governments and media sources except where its groups and shows were in a major action. Interestingly a white paper from the Washington D.C.- based Center for Strategic and International Studies cited MRA’s work at the end of WWII as “the main factor” in the post war French-German accord. The 2008 report states “this astonishing rapid accord is one of the greatest achievements in the entire record of modern statecraft.”

MRA used original films, musicals, and dramas, to spread its message to hundreds of thousands of people around the world – something no other social organization or movement had done prior to the 1950s (more about this at the end). Some of the films you’ll read about are Freedom about a West African country and its peaceful transition to independence, The Crowning Experience, a musical based on the life of Mary McCloud Bethune, the African American who overcame racial barriers to become founder of Bethune Cookman College in Florida. Another was Hoffnung written and produced by German coal miners.

The name Moral Re-Armament was coined by Dr. Frank Buchman, the founder, who was interviewed by a reporter in 1938 just as the flames of war were starting in Europe. He was quoted in the press as saying, “What the world needs at this moment in time is not military armament but moral and spiritual re-armament.”

While the general message of MRA through its productions and teams of speakers emphasized racial, class, political, tribal and cultural peace and reconciliation, the heart of the program was based on the very simple philosophy of people living by four absolute moral principles – honesty, purity, unselfishness and love. The other idea was that if people took time to meditate regularly, God, or God’s spirit, could speak to them to help them improve their lives and the world around them.

Dr.Frank Buchman was ordained in the Christian faith. However, he never pastored a church. Instead his work was in the social fields. Most of the original MRA full-timers were Christian but by the time we came along many of the committed leaders and spokesmen and women were from various religions and cultural backgrounds –Hindus, Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, and later Native, and even those of no organized religious faith. The idea of applying the four principles and meditation are common to most faiths and to most humans and was the basis, we believed, for how people could change to be change catalysts for change in the world.

How did we spend our time and what was our day-to-day work – performers, diplomats, missionaries, or ?

Most of the time we were part of a team or group especially while on tour. Others, often senior men and women with a title or official position, were designated the main speakers, we were the entertainment, often coming at the start of a program to “break the ice or warm up the crowd.” Because of our music, often singing in the language of the audience, we were also involved in meeting local leadership personally and sometimes part of ongoing conversations with them. If not involved in a tour or daily ongoing programs in a city, there were always team meetings and participation in activities of daily living wherever we lived. And there were always unique, fun times such as when five of us formed a basketball team and played several games against Ghanaian UN military teams in the Congo.

MRA and Communism

Reading the letters you could get the impression that MRA was anti communist. In a sense, we were. We were against the ruthless policies and world expansionism of the USSR and it’s dictator, Joseph Stalin who murdered and jailed millions in the late 1940s and 50s.

When we came aboard with MRA in the early 1950s the Cold War between the USSR and the Western democratic countries was in full swing. We witnessed first hand communism infiltrating all facets of life especially in trade unions in Europe, certain parts of the British press, student movements and in the independence struggles in Africa notably in the Congo.

The communism of Russia, later the USSR, certainly included the economic, anti-capitalist, class war, total government control of all facets of life systems of a nation’s life first initiated by Karl Marx, but also included the proliferation of their ideology to all corners of the world.

We wrote a lot about the ideological battle in the world. Communism is an ideology as is Fascism. MRA believed it was also an ideology, albeit a better one. By definition an ideology is a system of concepts, theories, and aims that constitute a sociopolitical program. MRA was apolitical and yet against any system of government and society that was dictatorial and not based on the basic tenants of a free society. On the other hand we didn’t let the western democracies off the hook in terms of their materialistic, often corrupt and self-serving ways. Many members of the Communist Party, by the way, came to realize the flaws in their ideology and began working with MRA programs.

Our personal struggles

Some parts of our letters speak about our personal struggles to live up to the lofty moral principles of the program. Self-introspection was part of the culture for those of us who were considered to be committed team members. One might say we were not unlike players on a football team who enjoyed the big games and travel, but sometimes the coach, in our case God, his spirit, our consciences or our “morally better” leadership, made us go back to the basics of blocking, tackling and running sprints to get into better condition, or for us, to get in better moral and spiritual shape to accomplish our job and walk our talk.

The full time life in MRA was maybe unique in the annuals of nonprofits in that those in it were together 24/7 and usually on the move, in our case for twelve years. The concept of changing the world starting by changing one’s self was sometimes taken to the extreme in people’s lives. Being absolutely pure was one of those lofty goals understandably hard for three young men. Another was absolute honesty pertaining not only to every day life and work but also about one’s sins and shortcomings, and then challenging new people to the movement to do the same sometimes being unnaturally aggressive. And then there was the concept of being a true “revolutionary” doing whatever is needed to advance the cause. Cases in point are parents working in different parts of the world while their children were left for long periods with nannies. In our case we left our parents (Ralph and Ted were just 16) but thankfully they, at least on the surface, acquiesced to the idea. And then there was the pressure to be more effective in changing others.

I think it is fair to say that the three of us believed that giving our lives to the advancement of MRA was a calling from God. Our introduction to the Christian faith came from our parents when we were kids. We were sometime church and Sunday school goers, you might say cultural Christians, but it was when we met MRA and started reading the Bible and going deeper into the subject of faith that I decided to become a Jesus follower. Our commitment was intertwined with our faith and work with MRA.

Another aspect of our journey was working out the normal friction that’s bound to happen between three brothers with very different personalities living and traveling together and often being called on to perform and write a song for some special occasion at the drop of a hat. We had our trials, got on each others nerves and sometimes one or the other of us wanted to quit. But thank God we didn’t because, who knows, if we had gone in a different direction or our separate ways, we most likely wouldn’t have been in a position to help start Up with People and more importantly wouldn’t have met our wives.

Our letters contain some abbreviations for words and also include words that may make you, the reader, scratch your head wondering why a certain word or phrase was used. It is not unlike people working, for example, for Microsoft in computer programming using phrases and symbols which only they understand. To facilitate your understanding of our letters I have compiled a list of ours at the end.

How and why did we get hooked up with MRA?

Someone asked us this question many years ago. How did we get into it? Ted, then in his early teens was famously heard to reply, “How did we get in it? What I want to know is, how do we get out?

In 1951 we were invited to see an MRA musical play called Jotham Valley at the Carthay Circle Theater in LA. The show, based on the true story of two brothers fighting over water rights in Nevada, interested us. At that time Ralph was just starting high school, Paul was starting his junior year, and I was starting my first year at Occidental College. We were taken by the play which was professionally staged and performed, but what interested us more was meeting the MRA cast after the show and at subsequent events at the MRA center in LA. They were a fun and outgoing bunch who were giving their time and lives for a purpose. They wanted to change the world. We liked what we saw and heard and it opened our eyes to a broader picture of what we could do with our lives and music. Being a part of changing the world? Wow! Pretty heady stuff for three teenagers.

And then there was the prospect of world travel and meeting national leaders who might be influenced to make a difference in their countries. At the time we were busy young guys, still in school and involved in team sports – Paul was on the varsity basketball team, Ralph star running back on the junior varsity football team, and I was on the college baseball team. Musically, we were performing regularly on TV with all the preparation and rehearsing that entails.

In the summer of 1953 at the ages of 16, 18, and 20 we were invited to attend MRA’s world assembly at Caux, Switzerland. We accepted and the rest is history as you’ll read in our letters.

Our brother, Ted

If Ted had been older when we started our band, we might have been a quartet with him playing the fiddle. However we did travel and work together later in South Africa and the Congo and he joined us briefly in various other countries. He followed in Ralph’s footsteps in foregoing his last two years of high school in San Marino and finishing his studies by correspondence while on the road with MRA. Instead of continuing our career path with Up with People he wisely chose medicine after serving two years as an officer in the army in Vietnam.

Epilogue

As I write this some 60 years or more years later I wonder, did we in fact change the world, the idea that caught our imaginations when we began. A lot of water has gone under the bridge in those six decades – the Moon landing and later the space stations with both Russian and American cosmonauts on board together, the Vietnam War, glasnost and the Berlin Wall coming down, China beginning to move away from the hard line of Mao Tse Tung, and many third world countries becoming independent. Did we and the MRA movement have any part in these changes?

In some cases more than others I posit we did. Take for example the rapprochement between France and Germany after WWII referred to above, and the return of Germany into European society and Japan into Asian. Did the fact that we wrote and sang a special song in very poor French for Robert Schuman, former French foreign minister and the architect of the Schuman Plan uniting Europe economically after the war, affect a new Europe? No, but the fact that many in MRA working in Europe did - was a factor. Was the fact that we talked with the then prime minister Kishi of Japan in the 50s and sang for him in Japanese before he went on trade tour of Asian countries, urging him to deal with the wounds of WWII before talking trade, affect the return of Japan to the family of Asian nations? No, but the fact that MRA groups worked for years after the war in Japan did.

The same could be said of South Africa. We were there in the late 50s. Did our presence singing in various local languages and interacting with all races play a part in that nation’s eventual freedom from apartheid? Maybe. But more importantly an MRA team of African nationalists and whites working there for many years did, I believe.

How about the ideological tug of war in Europe in 50s between the USSR’s attempt to communize the trade unions by means of strikes to paralyze industry and thereby win political power? We interacted with many trade unionists and industrialists especially Italian and German. We were a small part of a much larger team that in my opinion moved Western Europe into a free democratic economy and the longest era of peace, 75 years, in its history.

We were in Cyprus and Nigeria, two countries that became independent in our time. We should get no personal credit but again MRA teams worked in both for longer periods and those nations survived devastating civil wars.

What about the Congo, once called Zaire, and now officially Democratic Republic of the Congo? We were there at the time of its independence from Belgium in 1960 and stayed for more than a year broadcasting to the whole country daily radio shows. Apart from Congolese who remembered our songs for decades after we left, and the major efforts of our team, the verdict has to be negative. Today, unfortunately, it is still a mess largely due to corruption and greed on the part of its leadership.

In summary, in some aspects, problem spots in the world did change for the better. Let’s just say we were on the team that helped.

Through all the ups and downs (and there were far more ups) of those years I came away with a unique and wonderful experience of the world. It was an education that couldn’t be matched at universities like Harvard and Stanford. It has given me a world view that very few Americans understand today. It helped the three of us relate to the scores of young people who later took part in the Up with People program. It motivated me to seek opportunities during my retirement years to get to know “the other” in my area and help immigrants in the U.S. In the early UWP show there was a song called "The World Is Your Hometown". Lynn (Abba, Aunt Lynn) sang the lead. It still is my hometown.

Finally, I submit that those twelve years prepared us for playing a major part in the founding of UWP. It honed Paul and Ralph’s skills in writing songs that ultimately became some the most popular and meaningful ones in the UWP shows. Our experience of cultures and languages helped give us the tools to create musically and, educationally, to lead casts as they traveled all over the world. One of the most popular and memorable songs that Paul, Ralph, and Herb Allen wrote is called Moon Rider. It’s taken from the words of Captain Eugene Cernan, the last astronaut to walk on the Moon, as his space capsule returned to earth.

“I see the world without any borders, without any fighting, without any fear. So captain give the order we’re going to cross the next frontier.”

The next frontier is for you, our children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren who might be reading this. We hope you’ll take up the challenge and go out and change the world.

________________________________________________________________________________

Meanings of certain abbreviations and words used in our letters

- Meditation = Quiet time, QT, guidance, G, my G meaning my thought, plan, or idea.

- To win a person or group = They liked what they heard about MRA and to one degree or another accepted its precepts.

- Battle and/or fight = Unlike a regular 9 to 5 job we believed that our work was part of a world ideological struggle, often more urgent and harder than a so-called normal job.

- Force or team = We were usually working with others and referred to them as such.

- Revolution = We were promoting a moral and spiritual social revolution as opposed to, for example, the economic, godless, class war revolution of Communism.

- Change = To change someone meant to redirect a person’s life based on the principles of MRA.

__________________________________________________________________________________

More about the shows and theater productions of MRA

MRA’s very first musical was called You Can Defend America in the early 1940s which Senator Harry Truman commended for contributing to the WWII war effort. Next came The Forgotten Factor, a drama which helped heal labor and management strife during the war. The Good Road with its huge international cast toured war-torn Germany after the war. The musical play Jotham Valley, the one we first saw in LA, played to hundreds of thousands in countries such as India, Ceylon (now Shri Lanka), and Pakistan in 1952 – ’53. The musical The Vanishing Island, starring the well-known British actor, Reginald Owen, also played to thousands all over the world in 1957. MRA’s unique use of music and stage shows to “sell” its message to world audiences helped inspire the first UWP show, Sing Out 65. UWP inherited much of the know-how and logistics that MRA had developed in the previous 26 years.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Letters Home 2 - The rest of the story

October, 2020

The twelve years we spent with Moral Re-Armament (MRA) was a time of change, growth, and challenge that prepared us for the reason our Creator made us – to help lead the musical founding of Up with People (UWP).

(Note that I wrote HELP LEAD because although we were considered musical founders along with our dear friend and colleague Herb Allen, I have always honestly believed that without the dedication and experience of many hands and brains in song writing and performing talent, finance, PR, travel, executive leadership and those in stagecraft skills such as carpentry lighting, and sound, the Up with People show may never have been born.)

When we waved goodbye to our parents at the airport in August of 1953 we never dreamed that we were also saying goodbye to our American professional music career, our next levels of education in high school and college with our friends, to the competitive sports that we loved, and to the comfortable middle class home life that our parents created and nourished for us. As we winged our way over the Atlantic Ocean in our 4-prop engine DC-6 we never expected to be outside the U.S. at one point for nine consecutive years of the twelve. This was to be a three-week experience at the MRA international conference center in the foothills above Lake Geneva in beautiful Switzerland after which we would return to our weekly NBC TV shows, more sessions with Columbia Records, and getting together again with country music Hall of Fame writer Cindy Walker who had already especially written a song for us to record. We were in fairly good company with her as she had written for artists such as Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley. And besides, our fledging fan club was expecting us home.

During an Up with People reunion in the late 1980s, my brothers and I received a message asking us to come to a meeting of the Up with People board of directors. When we arrived, we were asked to wait outside as their semi-annual meeting was still in progress. After a while the chairman of the board appeared and invited us in to the meeting where we were notified that the board had decided to honor us as the creative founders of UWP. I was indeed honored to receive the official recognition. But even if that honor hadn’t taken place, I was fine in just knowing that my brothers and I were at the right place at the right time in the summer of 1965 and had the experience and, okay, the talent to be at the heart of the creation.

Over the next 50 plus years the outreach of Up with People got the headlines and was in the spotlight - the four Super Bowl appearances and all the unique venues such as Carnegie Hall, bull rings in Spain, opera houses in Italy, in countries such as Russia, China, Cuba, and Jordan. But later it struck me that something else was going that was maybe no less important and that moved me deeply to hear.

At Up with People annual reunions former cast member thanked me sometimes with tears of emotion for the fact that the experience they had changed their lives. Although I never had the chance to learn what that change meant in most cases, I’m sure different for different people, I believe for many it had to do with becoming world citizens living outside themselves with a sense of compassion for “the other” and for their communities. This was evidenced in awards presented to alumni at each reunion honoring those who were doing selfless service in their communities or for people in other countries. Yes, we need the big stages of the program, the Super Bowls and Chinas, but developing an army of men and women among the 22,000 alumni who give back to society, was a result that I never fully realized when that first cast left for Japan and South Korea in the Fall of 1965. And it must be said that I never took the gratitude that alumni expressed to me personally. I happened to be a face they recognized. I was the recipient at the moment, but I knew their words were meant for all of us including my brothers, and others who were considered founders.

This is why looking back over my eight plus decades I maintain that apart from we four brothers (including younger brother Ted) meeting our wives in Up with People, its creation is the highlight of my life. However, it probably wouldn’t have happened if we had not been through the life boot camp of the twelve MRA years. In spite of the challenges of that time I will always be grateful it happened. The following are a few of the things we learned and experienced that made us ready for the greatest opportunity of our lives.

First of all, all of this would not have mattered if we brothers had not remained together as a trio and with the program. And at times that wasn’t easy.

I quit

It always saddens me when I hear that siblings don’t talk to each other or worse, hate each other. My brothers and I have been fortunate. It’s fair to say we actually like love each other. After we began our families, we often shared vacations, holiday events, camping trips, and sports. A major factor in getting along has been acceptance – acceptance of each other’s quirks and personalities which wasn’t always easy especially in our younger years. Much credit most go to our mom and dad who loved us unconditionally and provided a stable, supportive, and peaceful home life. But lest anyone think we were too unique and perfect there were normal brotherly frictions brought about by our age stations in life and our competitiveness whether in running races on the beach, playing tennis, or having a pickup basketball game. Winning was the name of the game. Paul and Ralph would get into wrestling matches as kids but as the elder brother I usually stood smugly above the fray.

When our music career started, first as a casual hobby and later a serious one, I was the one who usually organized rehearsals, kept us on track, and later, was the point man dealing with the business end of things. Paul and Ralph were okay with this until my perceived bossiness rubbed Ralph, especially, the wrong way. Paul is the perfectionist not only in music but in everything which to his credit throughout his life has led to some very profound and timeless song lyrics. But his insistence on perfection sometimes led to friction with Ralph and me. Ralph, the youngest of the three, could occasionally not see the reason for rehearsing so much and being punctual whether to practice or to perform. Instinctively he knew he was talented enough to simply show up and our performance would be just fine. I, on the other hand, needed more practice to memorize lyrics and to perfect my part.

Speaking of Ralph’s talent, we took piano lessons as kids. Ralph didn’t like to practice. When our piano teacher came to our house for our weekly lesson, we each had to play the piece we were assigned. This is where Ralph’s quick study talent showed itself. He’d ask the teacher to play his piece once through pretending to not understand one part. Ralph watched and listened as the teacher played it and then copied exactly what the teacher just did. He was then praised for his diligent practice effort. By the way, in remembering Ralph who sadly left is in December of 2017, Paul and I unanimously agreed that Ralph was the star of our show.

These natural quirks in our personalities continued when we began our 12-year saga with MRA. Now even though we were maturing in our late teens and early 20s, we were together just about 24/7 and the pressure to do our unpaid job well whether performing in a foreign parliament or in the home of a dock worker was more intense. Additionally, it was in our nature to put pressure on ourselves. Sometimes Paul wasn’t the only one who demanded perfection in what we were doing. This exacerbated the friction between us.

In July of 1958 I write to our parents, “Ralph and I got into an argument. I realized where I had been wrong and apologized. Later I found out that Ralph was still mad at me. Our referee, Paul, got in the middle of it and pointed out that I often say and do the right things but don’t do it in the same way I’d treat a friend. If Ralph doesn’t measure up to the lofty ideals I have of our trio, my pride gets hurt and I lash out at Ralph.”

In October of that year as we were rehearsing to record for Philips Records in The Netherlands with our friends and mentors Tex Williams and Kenny Baker who were flying in from LA. Tex, as you may remember, was a popular country western singer and band leader who had the first million-selling record for Capital Records in the late 40s. During our rehearsals I became angry and frustrated as my brothers tried to correct me. “I will not be told what to do,” I wrote my parents. In fact, I was competitive and jealous of their talents. My position as self-appointed leader of the band was being challenged and this jeopardized my musical security. On top of that I felt Ralph was not pulling his weight and I became furious with him. Was the recording session to be cancelled? Well, we finally worked things out after I realized that I was subtly trying to dominate and control my little brother and apologized. Rehearsals continued and the recording session happened.

Over those years we learned the way of conflict resolution which was at the heart of the MRA philosophy. This meant being honest with yourself and looking at where you need to change first. This way of approaching conflict is encapsuled in a song we recorded called When I Point My Finger at My Neighbor There Are Three More Pointing Back at Me. On a broad scale it was between countries, races, in industry, classes, and tribes. But it also applied to families and in our case fraternal relationships. While this wasn’t a magical pill that ended all conflicts before they started, it gave us the tools to resolve them.

These are typical examples of the kind of friction that might have led to our musical demise causing the end of our MRA journey. Another was this.

In May of 1960 writing from the Congo, I told my parents that I wanted to quit. I was pissed off at my brothers and wanted to get away. Part of my frustration was also the fact that my stuttering problem was continually exacerbated by having to do public speaking as part of our performances and speak in our regular team meetings. This was one of the several times that I, and Ralph for different reasons, were at the point of throwing in the towel. Usually we would chicken out from actually taking the complicated action to find the money and book ourselves on a flight from wherever we were in the world – Hokkaido, Japan or Sicily, Italy for example – and then buck the pressure we’d get from our team. The other factor was that there always seemed to be that next exciting place in the world that was calling to us like the Congo performing at its independence celebration the next month.

One more issue regarding staying together. The Korean War was going on in the early 50s and the draft system was in place as it was during the Vietnam war. I was classified 1A, meaning first in line to be drafted into the army as was Ralph later on. Paul was deferred for health reasons. I was ordered to report for duty. However, one of the senior Americans in MRA went to bat for me and after many letters and appeals the government deferred me on the basis that what I was doing for the world was more valuable to the U.S. than carrying a gun in Korea.

All people everywhere

It looked like the United Nations or the new Jerusalem as recorded in Revelations in the Bible when we participated at the meeting the first day of the international conference at Caux in early August 1953. There were delegates from all over the world. I remember especially huge groups from many African countries and from the sub-continent of Asia and the Lord Abbot from Thailand in charge of some 200,000 Buddhist monks. Over the next 12 years including many conferences at Caux we rubbed shoulders with people from many dozens of nations of many different races, cultures, and ethnicities. I mention this because in the work, or maybe I should say the fun, of creating our first show called Sing Out ’65, about a dozen countries were represented. I believe our 12 years working in 37 countries helped give us a deeper understanding and appreciation of the various cultures, characteristics, and traditions of the mostly non-Americans working with us and those with whom we came in contact. Is it essential to experience international cultural relations before any good can be accomplished? No, but the better you can relate to people who don’t share your DNA, the more they will feel welcome and the better will be your working relationship. And it was more than simply working with “the other” in a conference setting. Caux conferences would sometimes continue for most of the summer months. During this time, we got to know people under many different circumstances - playing soccer, washing dishes, and as roommates.

Although UWP started in the U.S. and its operating base was there, it was always international in scope. Because of our twelve years with MRA on six continents (the only one we missed was Antarctica) we became knowledgeable and comfortable in relating to the cultures and languages of people outside the U.S. While a masters degree in international relations isn’t necessary to work in foreign lands, having been to places in the world which are different from Southern California is very important in developing good relationships with “the other.”

What Color Is God’s Skin? *

As I write in 2020 the U.S. is experiencing a new upheaval and awakening regarding race due to recent killings of African Americans by police. Growing up in Southern California and Indianapolis there were virtually no people of color in any of my schools. When we arrived at the Caux conference mentioned above, it was a surprise to be immediately interacting with so many people of color. There seems to be a proliferation of new books about the injustices of race and how it penetrates every facet of the American society. Education about racial issues from slavery to the civil rights years to the present prejudices of our society is worthwhile, but our education was one to one interaction with people of color, some ordinary, some who were part of the independence struggles in Africa and some who were fighting apartheid in South Africa.

My main take-away from those years was the practice and experience of looking into the eyes - brown, blue, black, green - of everyone with whom I encountered to understand their needs and wants, fears, worries, feelings and goals. As I look back now in my retirement years I wonder if I could have done more to personify the antidote to the hate and blindness of racism. I think of the prayer often repeated in church services, “forgive us for what we have done and for what we have left undone.”

* Title of a song by David Stevenson and Tom Wilkes from the words spoken by Peter Howard in a speech in the U.S. in 1964 at the height of the civil rights and racial equality struggle. One of the most popular songs in the Up with People shows.

Leaders and laborers, princes and paupers

During the twelve years we found ourselves performing for people from all walks of life in every circumstance imaginable – for kings and queens, CEOs and union leaders, presidents and prime ministers, waiters and cooks, in the Vietnam, Philippine, and Japanese parliaments, La Scala opera house in Italy, on top of wagons for farm laborers in Italy, under a tree in an Congolese village, Dutch Queen Juliana’s receiving room, a Filipino banquet hall and in the home of the communist dock union leader, Ted Bull, in Melbourne, that was so small we could hardly squeeze Ralph’s bass fiddle in. This idea of singing whenever and for whoever in any setting in order to promote our show and our message was common. Theaters with full sound and lighting capabilities were preferred but we learned to make do with any venue. That way of performing continued in the Up with People years.

Nonprofit organizations advance their mission by winning people to their cause. That was true with MRA and is true with Up with People. We try to reach and influence everyone no matter their work, history, or position in life. However, it’s obvious that a person high up in government, business, or society has the means to advance our nonprofit’s agenda faster and further than someone at the other end of the spectrum. Therefore, nonprofit leadership should target the top-level people spending more time and effort to influence them and bring them into your fold. More times than I could count, my brothers and I were involved in special meetings and occasions with dignitaries. This emphasis continued with UWP often with a whole cast 125 people performing for one person.

The flip side of coin is that from the very beginning of our involvement with MRA, attention was given to ordinary people who probably would not be involved in advancing our cause in terms of sponsorship or funding but were no less important to making the world go around - meal servers, cooks, drivers, day laborers for example. Frank Buchman, the founder of MRA led the way. Often after we performed for a special banquet dinner, he would ask all the waiters and cooks to gather around while we sang for them. Not a few times we’d stuff our instruments in a small European car and drive miles to the home of someone who had served us to sing a few songs for a special occasion like Christmas. Bottom line we received a good schooling in how to treat all people everywhere.

Developing the craft of song writing

There have been many talented composers and lyricists who are credited with songs that have been the heart and soul of the Up with People show legacy. We, or I should say mainly Paul and Ralph, have been among them. How did it happen that three country/bluegrass singers who only sang others’ songs in their early professional careers wrote more than 200 songs including some of the most long-lasting ones for UWP?

Not unlike any skill - physical, artistic, or academic - it simply takes practice and we had a lot of it. As we were constantly on the move, we were either asked or we volunteered to write a special song for the next city, country, or dignitary. Quite often it was on short notice which required all-nighters. Paul was usually our “point guard” as we wrote. Especially if it was at night my main job was to keep us on task and make sure we met our deadline. Ralph would often dose off but then wake up suddenly and throw in a great line or hook. Although from time to time we learned from and wrote with a few of MRA’s talented creative team, we were basically on our own. Over those years through trial and error we learned how to write lyrics that were thought-provoking, expressed elements of humanity and hope that would, with any luck, move and inspire people, and how to put humor in songs. There’s nothing like humor to break down barriers. We learned how to paint pictures and tell stories with words as well as find the hook in a song, the grabber, the word or phrase that makes the song special and interesting.

Speaking and singing in the other’s language

Another critical and common-sense aspect is language. Music in itself is the language of the heart everywhere. However, if music can be accompanied by lyrics that people can understand the effect of your effort is multiplied ten-fold. I have sometimes been asked what I considered the highlight of my Up with People years. Not easy to answer as there were many. But if pressed to say one, it was the first tour of Italy in 1968. Why? The main reason is because the whole show was in Italian. Since my brothers and I spent many months working in Italy while with MRA, we learned to speak Italian well enough to make ourselves understood. Ralph emceed the show in Italian and almost all of the songs were translated into Italian. The response from audiences was electric and in each city scores of young Italians wanted to either join the casts or create their own local Up with People shows.

In every country we visited our first and main priority was to learn or create a song in the language of the people we were visiting. If our stay was short and the local language was difficult for us, even inserting a few words into our music opened hearts. And isn’t that the ultimate purpose of music beyond simply entertaining? In our case both in MRA and later Up with People, we were attempting to convey a message of hope and positive change. But if the ears of the people to whom you are singing are not open to you or your message because of their feelings of bitterness for example, your message will fall on deaf ears and hearts. This, therefore, is the magic of taking the trouble to sing in a native language which is not the norm for most touring musicians.

An example was singing to the Japanese prime minister, Nobusuke Kishi, just before he departed on what was to be a trade mission to other Asian countries in the mid-50s. We sang a special song for him in Japanese that expressed the vision that Japan could be a lighthouse of peace and reconciliation for Asia. The scars of war were still raw and we were trying to convey the idea that although trade was important, approaching his neighbors with a humble and apologetic heart was vital in building new relationships and bringing Japan back into the community of Asian nations.

We also wrote a special song with the help our Japanese colleague Hideo Nakajima who as a teenager during WWII was trained to be a human torpedo. As he often quipped, “The war ended, so I didn’t go off. I’m still here.”) The idea of the song, called Masuguni which means straight, was that Japan in its rebirth after the war should pursue a national policy that was neither left nor right but straight.

Language was our weapon of choice everywhere we went. The longer we spent in a country the more of that nation’s lingo we learned or tried to. We spent all together at various times more than a year in Japan. I tried to learn to speak Japanese but never really succeeded. However even today I remember quite a few words and phrases which come in handy in conversing with Japanese acquaintances. Ralph and Paul became fluent enough in French to converse in French speaking countries. Over the course of our MRA and Up with People years we ended up singing in over 40 languages and dialects.

So now you’ve read the headlines of the rest of the story regarding our apprenticeship in music and life which brought us to the next and most important stage of our careers. There is much more to the story, part of which can be read in the book A Song for the World by Frank McGee. Otherwise, Paul and I would love to chat with you any time anywhere but preferably on a warm, tropical island.

English