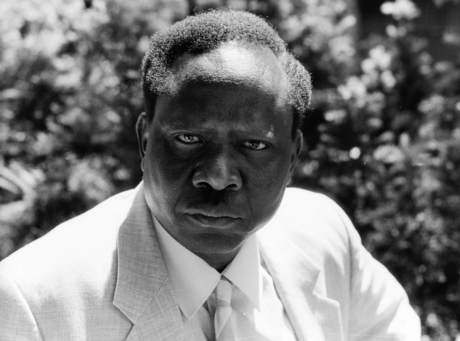

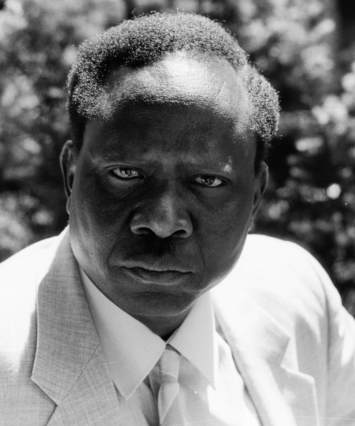

JOSEPH LAGU - peace builder and reconciler.

When President Numeiri’s government fell in 1985, his Vice-President General Joseph Lagu was briefly detained and then evicted from his official residence. With a wife and four children under 13, he had no roots in Northern Sudan and could not return to his home in the South where a second civil war had begun. He asked the British Ambassador for residence in UK and this was granted. Social housing was found for the family in Ealing, West London.

His wife Amna, who had overseen servants in the Khartoum residence, became a dinner lady in her children’s primary school. The General, who earlier that year had received USA Vice-President Bush at his Khartoum office, and represented Sudan at the Moscow funeral of Soviet leader Chernenko, could now only brood on his future in a land where he was unemployed and largely unknown. A lifelong Anglican, he meditated afresh on the implications of his Christian faith.

He still had many senior Muslim friends in North Sudan. They admired this guerrilla commander who had made peace with them in 1972 at the end of the first North-South civil war. One of them, Sayed Ahmed El Mahdi, advised him to be in touch with the work of Moral Re-Armament (MRA) in UK. Knowing me from my teaching years in Sudan, and as one who had met the General, Sayed Ahmed gave me Lagu’s London phone number.

MRA had an active work of reconciliation in over fifty countries. Those responsible for it realised that Lagu’s experience of post-war rebuilding had a relevance far beyond Sudan. In the next years he was invited to speak in Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and around England. Invitations came from fifteen other countries, from Cambodia to Salvador, as well as the international conference centres in Switzerland and India. He often took as the title of his talk The struggle for justice without hatred.

At the same time he was pursuing the new role he saw for himself as an African elder statesman. He lived passionately into the emergence of post-apartheid democracy in South Africa and corresponded with Nelson Mandela and other African leaders. Declining to join the second civil war in his country, he addressed the prejudice and injustice which had caused it, and maintained vigorous communication with both sides. In 1988 Prime Minister Sadik El Mahdi appointed him Roving Ambassador for Peace, based in London. This post was endorsed by the two governments that followed, and in 1991 he went to New York for a spell as Sudan’s Permanent Representative to the UN. From there he hoped to be appointed as UN Representative in a country emerging from conflict such as Cambodia, but this did not happen.

During General Lagu's first fifteen years in Britain he regarded me as his ADC. He consulted me on the wording of his statements and sometimes their content. Lagu entrusted me with the record of his writings between 1985 and 2000, and for years afterwards would ask for particular documents.

When South Sudan became an independent state in 2011 and he returned as Adviser to the President, his 1994 speech in Cameroon was the message he most wanted to give his countrymen. 'It is rewarding,' he said, 'to do what you believe to be right before God, as the silent voice tells you. Never give in to the wishes of other people contrary to that. Respond to the silent call within you, especially when you are the one accountable for a decision. Stand firm, even if at a price.' He also warned against anti-Arab racism.

One main source is his autobiography Sudan. Odyssey through a state, from ruin to hope, published in 2006 by M O B Centre for Islamic Studies, Omdurman Ahlia University. The full collection of these writings can be accessed at LAGU Durham Catalogue of papers.

Peter Everington was employed by the Sudan Ministry of Education in 1958 for eight years, first as a teacher of English in boys secondary schools (Port Sudan and Khartoum), and then as lecturer in English at the mixed Higher Teacher Training Institute in Omdurman.