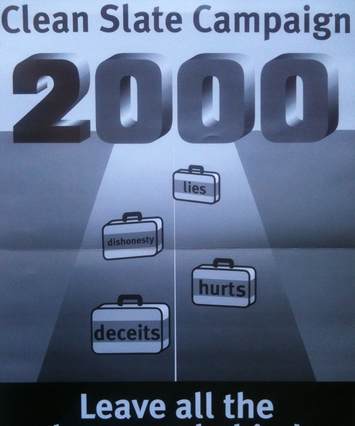

Article in The Glasgow Herald, linking to the Clean Slate Campaign.

Apologies are always tricky. We've seen the Sun's full-page, but rather unconvincing, effort at contrition after they had published an 11-year-old photograph revealing Sophie Rhys-Jones's breasts. We had Donald Findlay's resignation as vice-chairman of Rangers Football Club after singing sectarian songs. He conceded a serious misjudgment and added: "I apologise unreservedly for offence caused to anyone." Then there was the case of the 400 British Airways passengers wrongly told they were about to crash who were sent a box of chocolates by the airline to say sorry.

Three such different incidents illustrate that, to be effective, an apology has not only to be sincere, but seen to be so by the wronged party. From the reaction of the airline passengers, chocolates did not match up to the warning of death.The Scottish public appear to have had equal difficulty in reconciling the relish with which Mr Findlay appeared to sing the offensive lines with his regret. While the Sun's retraction was greeted with similar cynicism, the victim managed to extend some acknowledgment and nominate charities which should benefit as a result. It suggests that the best chance for success lies in personal offers and acceptances between two individuals.

The millennium has been a focus for grand projects, but there's still space among the new museums and public works for a bit of individual action, starting, possibly, with the next-door-neighbour you've been cold-shouldering for some transgression which history will hardly count as significant. The idea of wiping the slate clean as a new year's resolution multiplied a thousand-fold is the brainchild of Edward Peters. "Three friends had bad-mouthed me behind my back and I had responded in kind," he says. This particular quarrel had lasted 15 years, nevertheless, it had continued to prey on his conscience and Peters felt there was still time to extend the olive branch. His apology was accepted and his niggling conscience was replaced with renewed friendship.

It was one of a number of stepping stones which led to the Clean Slate Campaign. Another was the tale of the 14-year-old boy who stole from a shop only to find that his initial excitement was quickly replaced by guilt. He told his father who accompanied him back to the shop to return the stolen goods. He got a severe dressing-down from the store detective, but, recognising the boy's courage, he did not involve the police. "The second I got out of the store I felt great, absolutely amazingly free, and I vowed never to do it again," said the boy, whose father is one of the founders of the campaign.

"We know there won't be a sudden rush of bank robbers taking their loot back," says Christopher Morgan, the campaign director, but he hopes that the Clean Slate Campaign will provide a focus for individual analysis of our lives.

"Approaching the new millennium is a chance to have a think as well as a party," he says.

That chimes with John Chambers's view: "Very often anniversaries are a good time for thinking about things." For the past year he has been a minister in Inverness, but, as someone who has spent most of his life in Northern Ireland, he knows all too well the effects of suspicion, distrust and hatred. As chief executive of Relate, the marriage guidance organisation, there, he saw the cancerous effects of harbouring grudges and guilt.

"One of the things you come across when working with families is how often people are haunted by baggage from the past. When people get into difficulties in relationships, it is because of things from the past that they cannot let go of - even though the other person has died or they have ended the relationship with them," he says.

"The first stage is to be able to put into words what it is you are harbouring from the past. Very often when people are troubled by the past, there is a whole host of things they are not identifying. Putting these thoughts into words - sometimes to the extent of writing them down on paper and tearing it up - can bring a consciousness which allows them to disappear."

We should remember that a quarrel might not be what it seems, but a symptom of something more complex.

She was a lady past her middle years whose life had not been easy. Her wartime marriage had ended after just one week when her husband was killed. Her second marriage had ended in divorce and she had gone for counselling after experiencing difficulty in a new relationship. Although her second marriage was well and truly over, it was only after talking about what had happened in it that she found herself crushing a ring her husband had given her. It was a moment of symbolic release - and more potent than she or her counsellor had anticipated. Suddenly she was able to relate something that had troubled her for years but had never been able to tell anyone: that, as a girl of nine, she had been raped.

If you've searched your conscience and identified your task, how should you go about taking at least one practical step during 1999 towards wiping the slate clean?

"First, think carefully about why you want to wipe the slate clean and recall what the quarrel was about from your perspective, because it may have seemed quite different from the other person's perspective," suggests John Chambers. "Then you have to say sorry for what you did, because you realise that it must have been hurtful." He warns: "There is no guarantee that the other person will be able to accept that. Sometimes both people bend over backwards to blame themselves, or it may take a couple of days.The relationship is never exactly the same afterwards, but it can sometimes be richer."

We want to hear from Herald readers inspired to wipe their own slates clean in 1999.

There will be bottles of Herald champagne for the best stories. Entries to Clean Slate Campaign, The Herald, 195 Albion Street, Glasgow G1 1QP.

English