When I was about four, my parents met the Oxford Group (forerunner of Initiatives of Change). I believe it was a man called Stanley Toms who introduced my father, Gordon, and I think it was the Rev. Cecil Pugh who encouraged him to measure his life against absolute moral standards.

Usually my older brother, David, and I said goodnight prayers with our mother, but on one occasion Dad joined us. He said that just as we could talk to God, he could talk to us. I thought this was a lot of nonsense, but I was too polite to say so. I soon began, however, to get thoughts, such as to have a clean hanky every day whether I needed it or not, and not to make a fuss when I had to wear clean woolly stockings because they itched.

Sometimes we went to Uncle Cecil’s church instead of our own. I remember standing next to Geoffrey, Cecil's son, in their Sunday School, singing, He who would true valour see. We owe a lot to the Pugh family. Soon after the beginning of the Second World War, Uncle Cecil became an RAF padre and was posted to a huge RAF camp a few miles east of Bridgnorth in Shropshire. The family had a house in the town, 15 East Castle Street. In 1940, when invasion seemed imminent, they suggested that our family should leave London and go to Bridgnorth. My brother Peter went first and stayed in the Pugh home; I went next and stayed in a farmhouse two miles away; and Mother came later with David when he had finished his School Certificate exams. Then we all stayed in the farm. Dad had to keep the office going in London.

David, Peter and I had been due to go to Canada; we had our suitcases half-packed, ready to get a train to Liverpool. The boys were set to go to a family in Toronto who were involved with MRA and I was to go to another couple nearby. Then a ship, the City of Benares was torpedoed and most of the passengers and crew were drowned; only a few of the children survived. So the government stopped the evacuation scheme,

and we stayed with Mother. Happily for all of us, our younger sister, Elizabeth, was born on 17 May, 1941. She cleverly arrived on a Saturday morning so we were all able to go and see her instead of having to go to school.

In 1942 we all went back to London. We were returned to our old schools, though I had to go into a form below my previous one - I had stayed down a year in Bridgnorth because of prolonged ill health. We arrived in time for the doodle bugs. These were the Germans' secret weapons, flying bombs. You could hear them coming, but when the engine cut out you dived under the nearest solid piece of furniture, or into a ditch if you were outdoors, and waited until you heard the explosion. In all, 13 out of 113 houses in our road were destroyed or damaged in this way.

We had a map of Europe on the drawing-room wall and little flags to show where our troops were situated. Dad had had a concrete shelter built in our back garden, large enough for five people to sleep in. Anyone else had to sleep under a table in the house. Then we got a Morrison Shelter which was an iron table with cage-like sides which would sleep two people, head to tail. The theory was that it would be strong enough to hold up part of a collapsed building around you. None of these devices were enough protection from the rocket bombs which came later. They were launched from across the Channel, and exploded with tremendous force on impact with the ground. You heard the whine of their approach after they had landed.

Dad had written an ARP (Air Raid Precautions) booklet at the start of the war. He thought out everything possible to protect his family. At this stage in my life, I was on fairly good terms with Dad.

When the Allied invasion started in 1944, David was already in the Navy. He was a coder; all messages to and from the ship had to be in code. Should his ship get hit, the first thing he and the other coders had to do was throw the code books overboard so that they would not get into enemy hands. These books were bound in lead so they would sink. The codes changed every day. When the war was over, he came home with many an adventure under his belt.

I left school from the Sixth Form. I decided that I wanted to teach small children so in 1946 I took a place at Roehampton in South London.

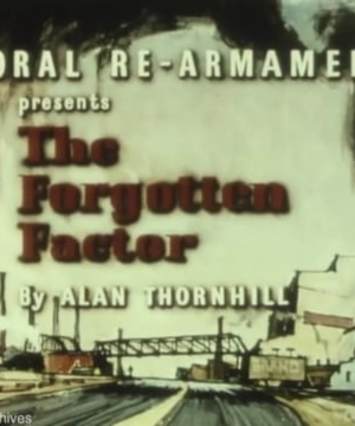

Around this time, 20 couples, including my parents, guaranteed the money to buy the Westminster Theatre so that MRA plays could be shown to the public. In the event, all the needed money came in, from dozens and dozens of people, including many ex-service people who gave their gratuities. A team of many people came over from the USA bringing the industrial play, The Forgotten Factor.

While this was happening, a chap called Will Kneale lodged in our house. After he had been de-mobbed from the armed forces, he began working full-time as a volunteer with MRA in London. He had no home, so Dad offered him a room in ours.

The full name of my college was The Incorporated Frobel Training College for Teachers. We First Years had to share study bedrooms and were placed alphabetically, except for me. For, lo and behold, whom should I be placed with but Joyce Kneale, sister of Will. She had actually got a place at another college but I believe Will had wangled things and got her transferred to Roehampton. So there I found myself rooming with this unknown character. As we First Years got to know each other and where we came from, people were much more interested in someone from the Isle of Man than someone from London. So I became jealous. We were chalk and cheese. You could draw a line across our room. I was tidy, Joyce was very untidy. I liked to be early for lectures and meals; she stayed in bed till the last minute. But one evening as she sat in her dressing gown in front of our gas fire I saw tears trickling down her cheeks. I knelt beside her and asked her what the matter was. She replied that she was thinking of her mother

who had died a few months previously. I felt most convicted that I had not cared for her. She talked in her sleep. Usually it was a jabber jabber, but one night she clearly said, 'I don’t like it alone here at the weekends.' I felt terrible because I had assumed that she would have been only too glad to have the room to herself and invite other girls in for a cup of cocoa. That weekend I had to go home because Mother and Dad were entertaining and I was needed on the Saturday and the Sunday, but I told Joyce I would come back to sleep on the Saturday night. It was an hour and a half’s journey home by bus and tube but I made it. That night we began to talk; we talked and talked till three in the morning.

After that I often took her home with me. We began to understand each other, but I still did not like her. One early morning as I was reading my Bible by torch-light under the bedclothes so that I did not disturb her, a Voice spoke very clearly to me, 'Joyce will be your best friend for the rest of your life.'

'No, Lord!' I cried, 'I’ll do my best to be friends with her for the three years we are at college together, but after that I don’t want to see her ever again, thank you very much!'

Well I knew I had to do something but all I could do was to pray for a love for her. Slowly and surely I began to appreciate her gifts. The next year we had single rooms and she was next door to me. Around this time, the college received some German visitors from a Froebel Institution. They had impressed Joyce very much, and somehow the things that her brother Will had said about healing relationships clicked into place. She came into my room early one morning and said that she would like to have a quiet time and what should she do?

I replied that she should take some paper and write down the four standards: absolute honesty, absolute purity, absolute unselfishness and absolute love, and see what thoughts came.

She sat on the end of my bed and began writing furiously. I sat up straight in the bed and thought, 'Help, I must have some “good” guidance to share with her!' That was the beginning. She had many things to put right with students and lecturers. Soon we had a team, for in our second year two young women who were already committed to living MRA - Meili Gillison (later Hawthorne) and Esme Dudeney (later Kirk) - came as First Years.

Joyce and I had many adventures together. We often totally disagreed with each other and had to battle things out. But we were honest, and slowly but surely we both changed to such a degree that although our paths went in completely different ways when we left College, we remained friends for life. I was privileged to speak at her funeral.

Life with Dad

As the years went by, I found it more and more difficult to get on with Dad. I thought he was weak, and I did not appreciate his finer qualities. When I was in the same room with him I contradicted him on every possible occasion. When he came home in the evenings after attending a meeting I would go to bed.

After two years of teaching in London I wanted to spread my wings, and with the help of various friends, applied for a job in Bristol. There was a strong MRA team there, and I got lodgings with the Sansom family. Dad was peeved that I had not consulted him about my move.

The school I was appointed to was 'The House in the Garden'. It was a couple of miles outside Bristol and the children were mostly children of dockers or people who worked in the aircraft factory where the famous Brabazon aeroplane was being built and tested.

At the end of the first year, Mother had arranged for a family holiday in Cornwall in a rented home. We invited Vivienne Sansom, the daughter of the family I was lodging with in Bristol, to join us. Brother David had other plans, but the rest of us went; Dad driving his car

with Mother, Viv and our sister, Liz, who was just 11. Peter was doing his National Service and followed us a day later on his motorbike.

It was the second or third night that the storm broke. It was ferocious; further up the coast a whole village was washed into the sea. I was sleeping on the sofa in the sitting room which was an annex to the main cottage. There were 13 clocks ticking and chiming away, and the wind and rain beat against three windows.

During the night, Mother got up to see if all was well. Dad said he would come too, but all he was in time for was to see Mother putting her hand out to switch on the light at the top of the stairs before she fell headlong down the whole flight and

hit her head on the stone flags at the bottom. She died almost immediately. Peter was the one Dad woke.

It was only the night before as I said goodnight to Mother that she had said to me, 'You must heal the rift between you and Dad.'

When Dad woke me up at six o’clock I first thought, 'How can I ever live with Dad without Mother to help me?'

We experienced many heart-rending days. But, as the years went by, life gradually settled back to some sense of normality. The family went their separate ways but we

always kept in touch. Years later when I was head of Penrhos Junior School, and we had a small house in the Hampstead Garden Suburb, my life with Dad was much easier. By this time Liz was married and living in Canada; Peter was married and he and Anja had their home in Budleigh Salterton; and David mostly came home in the school holidays as he, too, became a teacher.

One hot evening Dad and I decided to go to the theatre. I put on a long skirt, a pretty blouse and my clip-on earrings. I drove Dad in my car. The theatre was near the old Covent Garden vegetable market. It was so hot, all the audience walked into the street outside during the interval. During the drive home I put up my hand to finger an

earring. To my horror it was not there! (These earrings had been a 21st birthday present.)

Next day, Dad said he would go back to the theatre to try to find the missing ring. He went by public transport. In the early evening he arrived home, having enquired at the theatre and searched the gutters of the road outside. He was white with exhaustion. I went upstairs to change for supper and on opening my drawer I found a screw of tissue paper, which contained an earring. Heavens! I had never put on the second ring! Now I had both of them. How could I tell Dad? How could I not tell Dad? I went downstairs with an earring in each hand and told him how silly I had been, and could he

forgive me?

He put his head back and chuckled and chuckled and chuckled. 'Oh my darling,' he said. 'I am just so glad you have both your earrings!'

That finally healed the last vestige of division between us. He died in 1978 at the good old age of 88. I mourned him deeply.

Spanska