Diese Seite existiert in:

In the space of twenty years, at the beginning of the 20th century, the alpine pasture of the Monts de Caux went from three rustic chalets to one of the main tourist sites in Switzerland and the world. It witnessed the construction of two giant hotels, as well as two churches, a railway station, three skating rinks, a bobsleigh track, tennis courts... First the Grand-Hotel, which opened its doors in 1893, and then, in 1899, the construction of a huge terrace behind which the Caux-Palace was built, the centenary of which is in July 2002.

This happened thanks to the dynamism and vision of Ami Chessex (1840-1917), de Territet, and a group of Montreusians. The architect Eugène Jost (1865-1946) was also a man of the region who left his mark: to him we owe the Lausanne Post Office, the Montreux railway station, the Grand-Hotel de Territet and the reconstruction of the Montreux-Palace.

Ups and downs

The Caux-Palace, when it opened in the first week of July 1902, was the largest and most luxurious of the Swiss hotels. In its heyday, during the Belle Epoque, it hosted the jet-set of the pre-jet-set world: John D. Rockefeller, the Maharaja of Baroda, Sacha Guitry, Arthur Rubinstein, Prince Ibn Saud, the future king of Saudi Arabia, writers Rudyard Kipling, Edgar Wallace, Daphne du Maurier and Scott Fitzgerald. Princes of blood from St Petersburg and princes of fortune from Pittsburgh. Olympic skating champions train in Caux. The world bobsleigh, luge and ice hockey federations are formed here. Further up, the descent of the ‘devil's slope’ is considered one of the most difficult events in the new sport of skiing.

Then came the First World War: the palace stood empty for five years and lost a million francs. It reopened after the conflict, but seemed so old-fashioned that it was not until 1929 that its owners proceeded to refurbish it. By then it was too late: the Depression and the approaching Second World War led to its closure. In 1944, the building was requisitioned by the army to house soldiers from the British Empire, civilian refugees from Italy and, finally, Jewish survivors of the Holocaust.

A meeting place

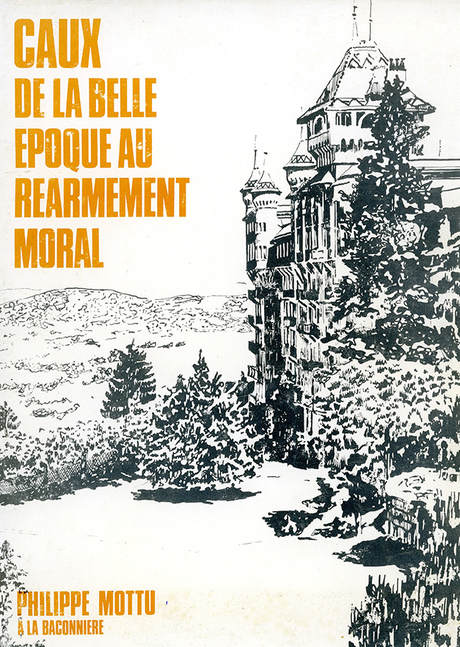

As early as the spring of 1942, a young Swiss man had a different vision of the future of Caux-Palace. If his country emerged unscathed from the war, he thought, the task of the Swiss would be to provide a meeting place for Europeans torn apart by hatred and suffering. ‘Caux is the place,’ he wrote in his notebook. Within weeks, Philippe Mottu and his friends decided to buy the building and the mansion was cleaned up and turned into an international meeting venue.

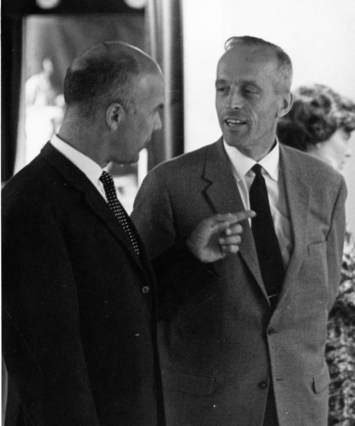

Historians have noted Caux's contribution to Franco-German reconciliation, hailed by Robert Schuman and Konrad Adenauer, two of the key players who made the journey to Caux. After that, the conferences each summer opened up to the whole world, to countries in the process of decolonisation, to ethical issues in business and the media.

Französisch