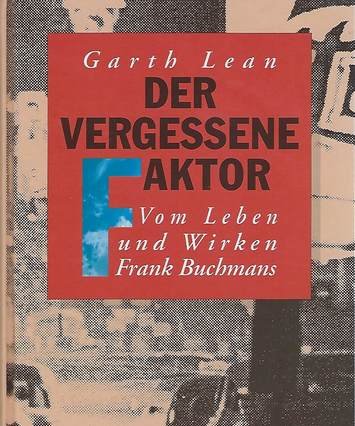

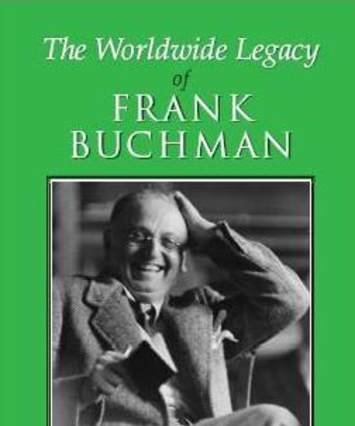

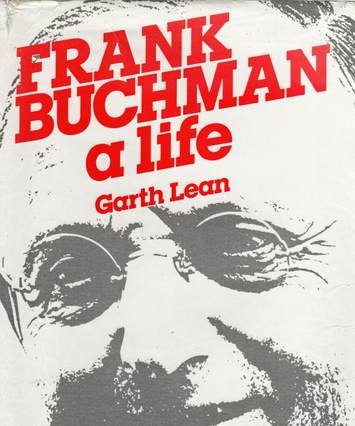

Frank Nathaniel Daniel Buchman was born in 1878 in Pennsburg, Pennsylvania, United States, the son of a wholesale liquor salesman and restaurateur and a pious Lutheran mother. When he was sixteen he moved with his parents to Allentown. Buchman studied at Muhlenberg College and Mount Airy Seminary and was ordained a Lutheran minister in June 1902. Buchman had hoped to be called to an important city church, but accepted a call to Overbrook, a growing Philadelphia suburb. He arranged the rental of an old storefront for worship space, and lived upstairs. After a visit to Europe, he decided to establish a hostel (called a ‘hospice’) in Overbrook. However, conflict developed with the hostel’s board. In Buchman’s recollection the dispute was due to the board’s unwillingness to fund the hospice adequately. Buchman resigned. Exhausted and depressed, Buchman took his doctor’s advice of a long holiday abroad. Still in turmoil over his hospice resignation, Buchman attended the 1908 Keswick Convention and in a small half-empty chapel he listened to Jessie Penn-Lewis preach on the Cross of Christ, which led to a religious experience. Buchman wrote six letters of apology to the board members asking their forgiveness for harbouring ill will. Buchman regarded this as a foundation experience and in later years frequently referred to it with his followers.

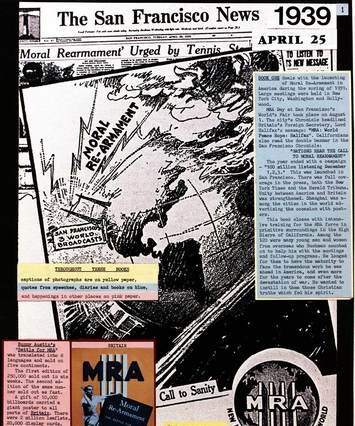

In 1938, as nations were rearming for war, a Swedish socialist and Oxford Group member named Harry Blomberg, wrote of the need to re-arm morally. Buchman liked the term, and launched a campaign for Moral and Spiritual Re-Armament in East London. More than just a new name for the Oxford Group, Moral Re-Armament (or MRA) signalled a new commitment on Buchman’s part to try to change the course of nations. In a speech to thousands on the Swedish island of Visby, he said: ‘I am not interested, nor do I think it adequate, if we are going to begin just to start another revival. Whatever thoughtful statesman you talk to will tell you that every country needs a moral and spiritual awakening.’

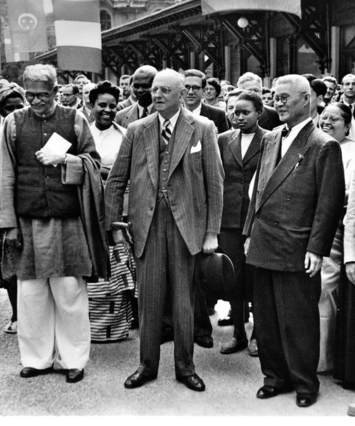

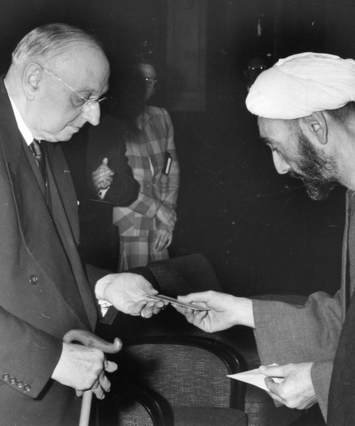

During World War II MRA’s efforts were valued by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a contribution to morale. After the war, MRA played a significant role in enabling reconciliation between France and Germany, through its conferences in Caux and its work in the coal and steel industries of both countries. Buchman was awarded the Croix de Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by the French Government, and also the German Grand Cross of the Order of Merit for this work.

Similarly, MRA facilitated some of the first large delegations of Japanese to travel abroad after the war. In 1950, a delegation of 76, including members of Parliament from all the main parties, seven Governors of Prefectures, the Mayors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and leaders of industry, finance and labour travelled to Caux, and from there to America, where their senior representative, Chorijuo Kurijama, spoke in the Senate apologizing ‘for Japan's big mistake’.

MRA played an important role in the peaceful decolonization of Morocco and Tunisia. In 1956, King Mohammed V of Morocco wrote to Buchman: ‘I thank you for all you have done for Morocco, the Moroccans and myself in the course of these last testing years. Moral Re-Armament must become for us Muslims just as much an incentive as it is for you Christians and for all nations.’ In December of that year, President Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia declared: ‘The world must be told what Moral Re-Armament has done for our country.’ But attempts to provide similar mediation in Algeria failed. In 1955, Buchman suggested to a group of African leaders from several countries meeting in Caux that they put what they had learned of MRA into a play. The play, Freedom, was written within 48 hours and first performed at the Westminster Theatre a week later, before touring the world and being made into a full-length colour film. In Kenya the film was shown to the imprisoned Jomo Kenyatta, who asked that it be dubbed into Swahili. The film was shown to a million Kenyans in the months before the first election. In the spring of 1961, The Reporter of Nairobi wrote: ‘MRA has done a great deal to stabilize our recent election campaign.’

He died in Freudenstadt, West Germany, at the age of 83.